Highlights

- Recent research ties sexually explicit music and teenage sexting. Post This

- The more teenage boys listened to sexually explicit music, the more likely they were to engage in sexting two years later. Post This

- New research suggests that listening to highly sexual music influences teenagers' sexual risk-taking, specifically sexting. Post This

For many families, music is woven into the fabric of our relationships and memories. In my family (Jane), nothing stops an argument in its tracks like someone turning on my siblings' childhood favorite, the 60’s folk group The Kingston Trio, and it isn't Christmas until we have blasted Alan Jackson’s “Let it be Christmas” and sung along slightly off-key.

Music can also be personal. As teenagers, we both listened to music while driving to school, working on homework, hanging out with friends, and during sports. Music is so common we never really think about the lyrics. As parents, how often do we stop to think about what our families and teens are singing along to or about, and what messages these lyrics are sending?

Perhaps this is unsurprising but studies have found that almost 40% of top billboard songs contain sexual lyrics, with some genres having up to 65% of sexually objectifying themes. You might have heard popular songs such as Hozier’s“Take Me to Church” with its purity culture critique, as well as the recent 2023 Grammy-award winning “Unholy” by Sam Smith and Kim Petras, which describes an unfaithful husband’s affair. Both are examples of mainstream songs with sexual lyrics that are frequently repeated on the radio.

Why does this matter? It’s common for parents today to worry about what their teenagers are seeing on social media platforms or TV, and often a lot of effort and care goes into trying to help teenagers develop a healthier relationship with media, as well as into steering them away from bad influences.

Because of the prominent place of music in our society, it is easy to treat music, and highly sexual and sexually objectifying lyrics in particular, as white noise in the background of more important activities, despite research suggesting that music contains more messages about sex than any other media content except pornography. It is easy to dismiss the lyrics and messages in a three-minute song as inconsequential, but our research, published in Computers in Human Behavior, suggests that listening to highly sexual music influences teenagers' sexual risk-taking, specifically sexting.

Sexting—i.e., sending or receiving nude/partially nude pictures or sexually explicit written messages to others via texting, social network sites, apps, or other forms of communication such as email—has been linked to potentially severe consequences for teenagers, such as poor mental health, and the possibility of future exploitation (also known as sextortion).

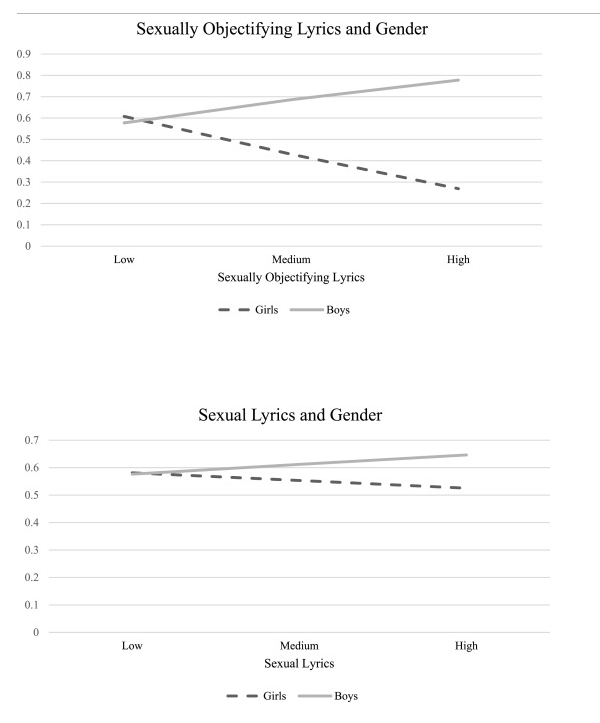

In our recent study, we tracked the number of sexts sent and received from teenage participants for three years. In the first and last year of the study, we also asked teenagers about the music that they listened to and were able to quantify how sexually explicit or sexually objectifying the lyrics to their favorite artists were. For girls, we did not find a relationship between listening to sexual music and sexting. However, the more teenage boys listened to sexually explicit music, the more likely they were to engage in sexting two years later.

So, what does this mean? Research suggests that boys are influenced by what they see (and in this case, hear) as “normal” sexual behavior from media influences and peers. Sexual lyrics may become an agent in normalizing that behavior. Girls, on the other hand, are often discouraged from sexual behaviors, which might be why they are less likely to be influenced by music.

Although girls might not be directly impacted by listening to sexual lyrics, this does not mean they are not affected at all. Studies have shown that a common motivation for girls to sext is coercion, and boys have been found to be more likely to pressure girls into sending sexually explicit messages/pictures. In this way, sexually explicit music likely influences how all teenagers think about, and participate in, risky sexual behavior. This suggests that although our findings show that sexual lyrics are more predictive for boys’ sexting behavior, parents of all teenagers have reason to think about how the sexual nature of music might be influencing their teen.

Given these findings, what can parents do with this information? Importantly, it is difficult, if not impossible, to stop teenagers from ever hearing music with sexual lyrics. So the goal for parents should be to pre-arm (think prepare), rather than cocoon (or completely shield) their teens. We offer a few suggestions along those lines:

- First, parents need to remember that despite what it may seem, they do have a lot of influence on their teens. Having an active role in shaping how teenagers think about risky sexual behaviors, such as sexting, may be difficult but it is worth it.

- Second, knowing more about the role music plays in how teenagers think about sex and sexting should be seen as empowering, rather than alarming, as it can help guide proactive parenting.

- Third, understanding that listening to sexual music lyrics is related to attitudes about and participation in risky sexual behaviors (sexting) indicates that music may be a helpful tool to breaching hard conversations, making music a valuable tool for parents.

Although music is often overlooked when parents think about media, sexual lyrics play a significant role in shaping teenagers' risky sexual behaviors, especially for boys. This hidden-in-plain-sight medium has great influence, but that doesn’t have to be bad news. So, the next time you and your teen are in the car, singing along to a favorite song, perhaps follow up by bridging your favorite music to a meaningful conversation about healthy sexual behavior.

Christine Lee is a undergraduate student in the Communication department at the University of California, Davis. Jane Shawcroft is a PhD student in the Communication program at University of California, Davis. She studies how we can leverage media and technology for the physical, social, and emotional health of children, teenagers, and families.