Highlights

- The COVID baby bust was heavily driven by foreign-born moms, including those barred from entering the country by pandemic-induced restrictions. Post This

- The increase [in births] was highest among the demographic subgroups most likely to benefit from more flex work/work-from-home opportunities. Post This

- The authors find the strongest effects among first-time moms, women under 25 and ages 30-34, and also women with a college degree. Post This

There was a once popular saying you might still remember: “two weeks to slow the spread.” When the first cases of a new coronavirus were being reported on U.S. shores and the country began to cancel events, there was lots of idle speculation about a hypothetical baby boom ensuing nine months later. Faced with a couple weeks with nothing else to do at night, it was thought that couples might use the opportunity to, as the Boston Globe put it, “frolic productively.”

But we are all too familiar with how those “two weeks” turned into a major adjustment to how life is lived (the person I saw just last week pushing a stroller while wearing a mask is evidence that the shock has proven semi-permanent.) IFS’ Lyman Stone was one of the more persuasive voices contemporaneously arguing that there would be no COVID baby boom. And research from University of Maryland’s Melissa Kearney and Wellesley's Phillip Levine suggested the coronavirus might result in a “missing” 300,000 or so births, relative to what might have been expected.

Fertility did virtually flat-line with the pandemic. But a new working paper nuances that finding in a significant way. Working with restricted-access data made available by the National Center for Health Statistics and the California Department of Public Health, UCLA’s Martha J. Bailey, Janet Currie of Princeton University, and Northwestern’s Hannes Schwandt find that the picture is more complicated than the top-line numbers suggest.

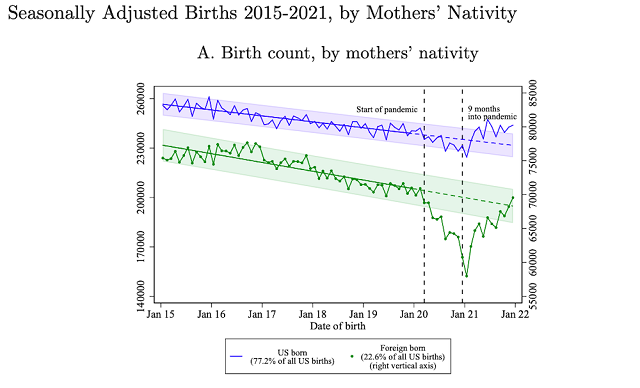

The biggest value-add from their paper is enabled by the restricted data; they are able to decompose the number of babies in the U.S. born to native-born women and those born outside the country. Doing so, they find that the COVID baby bust was heavily driven by foreign-born moms (see chart from the paper below), including those barred from entering the country by coronavirus-induced restrictions.

Source: Bailey, M., Currie, J., & Schwandt, H., "The COVID-19 Baby Bump: The Unexpected Increase

in U.S. Fertility Rates in Response to the Pandemic," Working Paper, NBER, Oct. 2022

Foreign-born women have comprised an increasingly large share of fertility in the United States. According to the Pew Research Center, 7% of total births in 1970 were to women born outside the U.S.; by 2007, that fraction had reached one-quarter. The NBER paper by Bailey, Currie, and Schwandt finds that in 2019, 22.6% of all babies born in the U.S. had foreign-born mothers. Some were documented or undocumented immigrants to the U.S., permanent residents, or students, and some traveled to the country to give birth.

The authors find that the plunge in non-native fertility occurred in the months immediately after the onset of the pandemic, too soon to only be reflecting a decline in conception. Since it is extremely unlikely women who conceived nine months prior, in the summer of 2019, were anticipating the onset of a pandemic, the initial decline seems likely to have been driven by travel restrictions preventing women from places like China from coming here.

Non-native moms from Latin American countries experienced a quicker rebound, even while pandemic-related travel restrictions were still in place, which the authors see as evidence that foreign-born women already living in the U.S. may have experienced a similar pattern to native women. The “sharp declines in the entry of foreign-born, non-resident mothers into the U.S.,” the authors write, stands in stark contrast to the “little evidence of a protracted baby bust” for U.S.-born mothers.

It is important to interpret these findings as being relative to a linear trendline projected forward from 2015 to 2019, rather than just year-on-year changes. (For instance, the authors point out that the decline in fertility to foreign-born mothers seems to have begun in earnest in the early part of 2017, a fact that may be of passing political interest.) When they report that U.S. fertility rates dropped by 2% in 2020, or rose by 1% in 2021, they are comparing that to the counterfactual in which the U.S. fertility rate continued its downward trajectory pre-pandemic.

So, their finding that native-born women increased their fertility by over 5% relative to the counterfactual is a truly remarkable occurrence; but, for comparison’s sake, that rebound puts the overall number of births back to where it was in 2019. The authors find the strongest effects among first-time moms, those under 25 and those ages 30-34, and also among women with a college degree, suggesting couples who may have otherwise put off starting a family decided to take advantage of the newfound flexibility of a post-pandemic world. (Among the subgroups of native-born women that did not see a mini-boom in fertility were women ages 25-29, Black women, and moms with two or more children already.)

Of course, other factors may have been at play as well. Massive fiscal stimulus under the Trump and Biden administrations left many American households’ balance sheets far rosier than prior to the pandemic (and helped fuel the high levels of inflation we see today.) Helping would-be parents feel richer would be expected to lead to higher fertility rates, even if the broader macroeconomic context remained unsettled.

In addition, a number of states enacted restrictions on abortion during the time in question, most notably Texas. Though most estimates suggest these bans wouldn’t have had a massive impact on the number of children who are born, as women take more steps to avoid pregnancy to begin with or simply travel to another state, they could have helped push up the birth rate as well.

Correcting the record about native- and foreign-born fertility is a useful insight from this paper. But an arguably more important takeaway—that women with a college degree, especially those becoming moms for the first time, saw a rise in fertility—should inform our broader conversations around fertility preferences and public policy. The fact that first-time moms were more likely to have children, while those struggling to balance their kids’ school closures and lack of child care did not, suggests that those early hypotheses about which couples would have time to “frolic productively” may have been on to something.

We may not be able to tell for certain what the fertility rate would have done in the absence of large-scale federal spending. But the fact that the increase was highest among the demographic subgroups most likely to benefit from more flex work/work-from-home opportunities, is useful for proponents of pro-family policymaking. It should serve as an essential reminder that tradeoffs are not improved by simply spending more on child benefits. Taking steps to make having kids less burdensome means changing the calculus facing parents and would-be parents. The post-COVID world of greater workplace flexibility seems to have helped achieve this for a surprisingly large number of new parents.

Patrick T. Brown (@PTBwrites) is a fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center. He writes from Columbia, South Carolina.