Highlights

- The great decoupling of marriage and parenthood that exploded in the second half of the 20th century is starting to be rolled back. Post This

- While Americans are having fewer babies, the babies that are being born are more likely to be born to married parents. Post This

- The silver living on America’s fertility crisis is that it may end up helping bring our outlier status of being the nation with the most kids raised in single-parent homes back in line with international norms. Post This

How hard do we have to look for a silver lining to the birth dearth? For those who care about the share of children growing up with the “privilege” of a two-parent household, maybe not that far at all.

New 2022 data confirm a trend that has been slowly evolving since 2007; namely, that the great decoupling of marriage and parenthood that exploded in the second half of the 20th century is starting to be rolled back. That’s because while America is having fewer babies, the babies that are being born are more likely to be born to married parents.

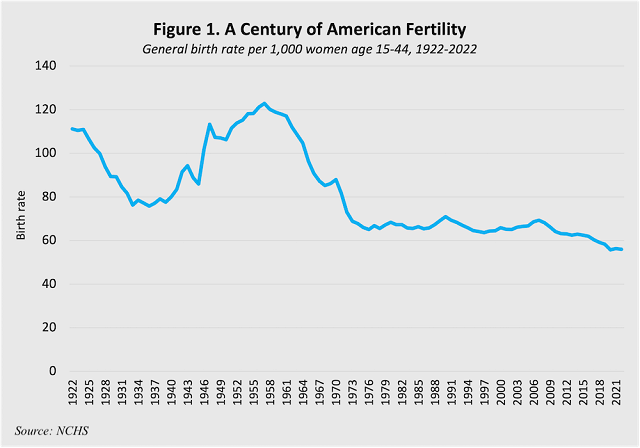

The U.S., like nearly every other industrialized nation, has seen fertility rates continue to trend downwards. In the official stats for 2022, released last week by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the nation’s general fertility rate—total births per 1,000 age 15 to 44—dropped to a new low at 56. It’s been on a steady nosedive since 2007, when the overall fertility rate was 69.3.

To put that in simpler terms, 2007 saw the largest number of babies born in the U.S. in a single year at 4.3 million. Last year fell about 650,000 short of that high-water mark, with a total of 3.67 million babies born nationwide. That was statistically unchanged from the prior year, with the long-running decline in rates of childbirth among women under age 25 counterbalanced by a notable increase among women in their 40s.

An aging, increasingly childless America is cause for alarm. We should seek policy and cultural changes to make it more affordable and appealing to have children.

But the news about declining fertility from the past decade-and-a-half is not entirely bad.

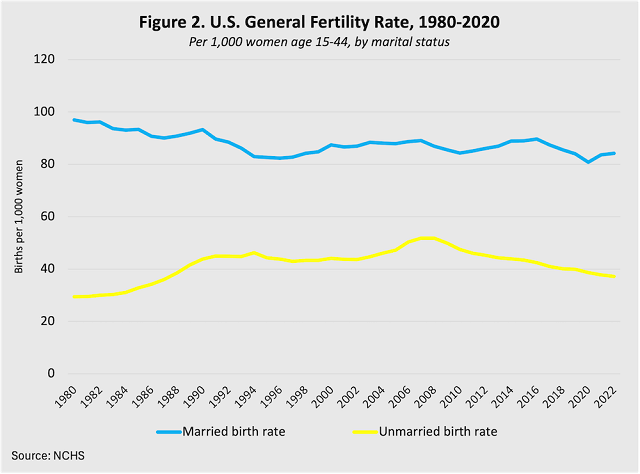

The birth rate among married women, which drifted down from well over 100 babies per 1,000 married women prior to the introduction of reliable birth control, has been in the range of 80 to 90 births per 1,000 married women since the early 1990s. Married fertility has dipped a tad since 2016, and it hit a new low of 80.8 in 2020. But 2022 shows a continued, if modest, rebound to a birth rate of 84.2 among married women.

The big story in family breakdown for much of the past half-century had been the increase in single parenthood. The birth rate among unmarried women ages 15 to 44 rose from 21.6 per 1,000 in 1960 to 51.8 in 2007. The concerns around family breakdown highlighted by original generation neoconservatives like Daniel Patrick Moynihan and James Q. Wilson were grounded in reality. But ever since the Great Recession, birth rates among unmarried women have begun to ebb, dropping again last year to 37.2 per 1,000. The last time America had an unmarried birth rate so low was in 1987.

A large reason behind lower childbearing is that more women are opting to marry and have babies at later ages. This has long-run effects on the total fertility rate. More women waiting until later in life to become moms means they are more likely to have one, or zero, kids, rather than two or three. An increasing share of young adults—particularly among those without a college degree—may never feel “ready” for marriage at all, which will result in rising levels of childlessness. Fewer high school students place a heavy emphasis on having a ring or a baby carriage in their future. And social conservatives, who place a high moral importance on the developing unborn child, can rightly worry that the decline of nonmarital childbearing is at least partly driven by wider accessibility of self-induced, or chemical, abortions.

The shift in fertility patterns post-Great Recession suggest a future in which fertility, like marriage, becomes the cherry on top of a successfully-completed young adulthood. Johns Hopkins’ sociologist Andrew Cherlin dubbed this changing view of marriage the shift from a "cornerstone" to a “capstone” model. Perhaps something similar is happening with parenthood.

If this is the case, it stresses the importance of conceptually distinguishing between policies that seek to increase the number of births (often called pro-natalism) and a fuller understanding of supporting the family as the core unit of a healthy society. The loudest voices raising concerns about the need to have more babies, like Elon Musk or Simone and Malcolm Collins, tend not to stress the link between marriage and parenthood. But this is shortsighted. Marital fertility rates are not only higher than among unmarried women, but the kids that are born benefit from a more stable home environment and the care and attention of two adults.

As I wrote in the March 2024 issue of National Review,

If you’re concerned about declining fertility, you must be concerned about declining marriage. Reshaping the cultural narrative about marriage, and making it financially easier and more culturally acceptable to marry earlier, will give the most couples a better chance to have more children. A natalism that underemphasizes marriage will fall short.

There is plenty of work to be done to help men and women integrate parenthood with their careers—starting in college, as the Niskanen Center’s Leah Libresco Sargeant recently argued for Deseret News. There are no shortage of policy and civil society initiatives that could stress the benefits of marriage for adults, as IFS’ Brad Wilcox covers extensively in his new book, Get Married.

The silver living on America’s fertility crisis is that it may end up helping bring our outlier status of being the nation with the most kids raised in single-parent homes back in line with international norms. Initiatives to prop up the birth rate that do not aim to confirm the trend towards more children being born to married households are misguided and possibly counterproductive.

Like it or not, Americans will be having fewer babies for the foreseeable future. This brings with it real concerns—economically, socially, and politically. Yet we should be provisionally grateful that our low fertility future seems likely to be the version that treats becoming a parent as something worth being undertaken prudently, rather than one that seeks to further divorce parenthood from marriage.

Patrick T. Brown (@PTBwrites) is a fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center. He writes from Columbia, South Carolina.