Highlights

- Increasingly, it’s not our friends, siblings, and churches that serve as mediators between us and potential partners; apps and websites and their algorithms do. Post This

- It could be a bad thing for relationships to start completely outside of existing social connections, and perhaps there’s such a thing as too much choice—especially if it leads people to waste a lot of time sampling the possibilities. Post This

My wife and I met as freshmen in a small college astronomy class in the spring of 2003. Neither of us even had a cell phone, and smartphones weren’t yet on the market. At the time, it was rare to find a romantic partner online: state-of-the-art communication tools, such as AOL Instant Messenger, were mainly used to talk to people you already knew. (My screen name was “loudguitars1.”)

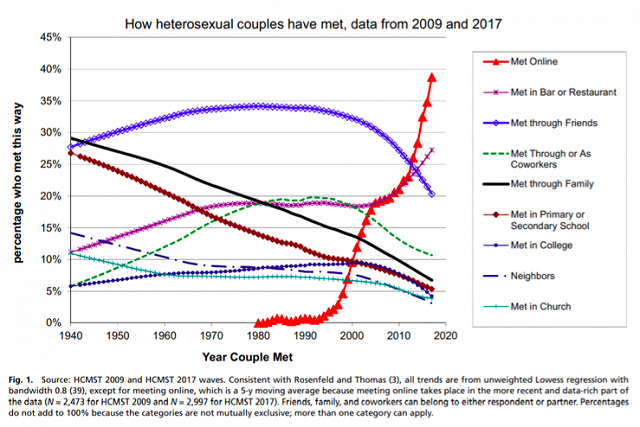

Young people today are doing things differently, according to a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences this week. (There’s an ungated draft here.) Combining the results of surveys conducted in 2009 and 2017, three researchers led by Stanford’s Michael Rosenfeld were able to plot the ways people met their partners against the years in which the meetings took place.

Source: Rosenfield, Michael J., et al., Disintermediating your friends: how online dating in the United States

displaced other ways of meeting, PNAS, August 2019.

As the figure illustrates, meeting online is up, up, up, while pretty much everything else is trending downward. Don’t let “bar or restaurant” fool you: The answers aren’t mutually exclusive, and this category’s skyward trend is driven purely by people who connected online and got drinks or food for their first in-person meeting.

As the authors note, these findings end a debate about whether the Internet and especially smartphones would function socially the same way that previous innovations, such as landline telephones, did. It used to be that technology just helped us communicate more efficiently with our preexisting acquaintances, family, and coworkers. Now it helps us find and connect romantically with total strangers. In the 2017 survey, 90% of those who started their relationships online had no other connections to each other. Increasingly, it’s not our friends, siblings, and churches that serve as mediators between us and potential partners; apps and websites and their algorithms do.

So, is this a good or bad trend? The new paper doesn’t dwell on the question too much, but it’s worth asking.

In theory, it could go either way. On the one hand, sorting through potential partners online could help people find better matches more quickly, both with the help of algorithms and just by speedily ruling out possibilities on the basis of the information provided. A lot of pointless dates, and even some doomed relationships, can be avoided if you know the deal-breakers before you even, say, look into their eyes and say hi—things like whether someone is looking for a serious relationship, whether they want kids, etc.

On the other, it could be a bad thing for relationships to start completely outside of existing social connections, and perhaps there’s such a thing as too much choice—especially if it leads people to waste a lot of time sampling the possibilities. In Cheap Sex, Mark Regnerus notes that online dating might work as an incentive to end existing relationships as well, by making new partners easily available. It’s further possible that online information can’t predict the romantic chemistry that it takes to get a relationship off the ground and keep it going. And just in general, given all the ways that smartphones can degrade our personal interactions and relationships, including by keeping married people in touch with their exes, we certainly shouldn’t assume that the good will win out in the specific case of online dating.

However, while the research in this area is hardly dispositive, in general, it suggests that online dating might be a good thing, or at least a neutral development. A 2013 study, also in PNAS, found that “marriages that began on-line, when compared with those that began through traditional off-line venues, were slightly less likely to result in a marital break-up (separation or divorce) and were associated with slightly higher marital satisfaction among those respondents who remained married.” A 2017 study by Rosenfeld similarly found that “meeting online does not predict couple breakup,” even though it did predict “faster transitions to marriage for heterosexual couples.” There’s also some evidence that online dating increases interracial marriage.

In the first two studies mentioned in the paragraph above, though, it’s difficult to rule out “selection effects.” In other words, it’s possible that people who date online disproportionately have other, unmeasured traits that make them less likely to have fragile marriages—and the studies may be picking up the effects of those traits rather than the effect of online dating itself. (The interracial-dating study, by contrast, looked at the rollout of broadband technology, treating it as a natural experiment, a somewhat stronger method.)

But even if we can’t definitively rule out the possibility that online dating increases the risk of tumultuous relationships, certainly there is little actual evidence in favor of it. If anything, the correlation seems to run in the opposite direction.

It’s worth studying the issue much more, and also looking at the many other outcomes that online dating could affect—including promiscuity, age at first marriage, divorces among older people wanting to play the field, etc. But for the time being, there’s no need to fret about your 24-year-old’s OKCupid account. Perhaps it will even lead to a happy marriage and grandkids one day.

Robert VerBruggen is an Institute for Family Studies research fellow and a deputy managing editor of National Review.