Highlights

- Ever-married shares today are at historic lows for 35-year-old and 45-year-old men and women. Post This

- Only about 60% of 35-year-old men are ever-married today, down from 90% in 1980. Post This

- Plausibly, one-third of men and women who turn 45 in 2050 (those who are about 18 or 19 today) will not have married. Post This

Editor's Note: Our 9th most popular blog post of this year is from Lyman Stone, Director of the IFS Pronatalism Initiative. This article, which projected the future share of unmarried young adults, was first published in February 2024.

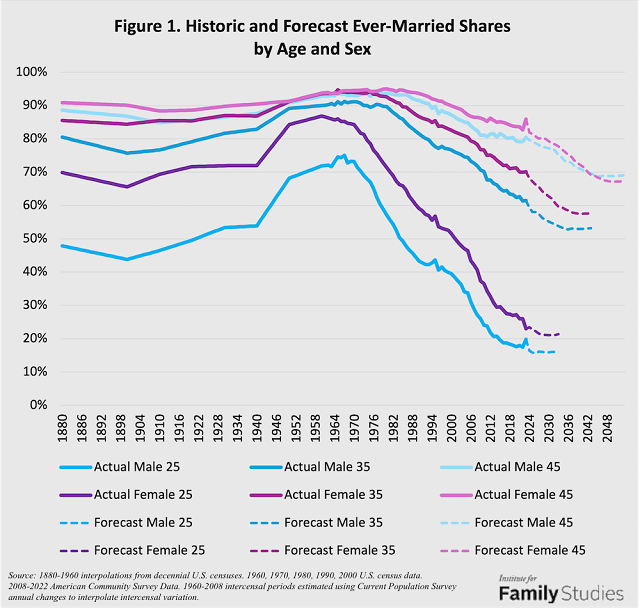

In 1967, about 85% of 25-year-old women had ever married, along with 75% of 25-year-old men. This was the height of the Baby Boom years. Unfortunately, these marriages also ended up having the highest divorce rates observed in American history. But those rates were also unusual: in 1920, just 70% of 25-year-old women and 50% of 25-year-old men had ever been married. There’s no reason to suppose young-adult marriage rates ever could have, or even should have, remained at Baby Boom-era levels.

Nonetheless, it is striking that just 20% of 25-year-old women and 23% of 25-year-old men have ever married today. These are close to the lowest levels ever observed for marriage rates. Many commentators will blame these declines on the increased delay in marriage. While there’s some truth to this, the situation is extreme at higher ages, too. As the figure below shows, ever-married shares today are at historic lows for 35-year-old and 45-year-old men and women. For instance, only about 60% of 35-year-old men are ever-married today, down from 90% in 1980. This trend also suggests that a growing share of Americans will not get married before their healthiest years are long past them.

This figure also shows dotted lines for forecasts (or future estimates). I forecast rates by taking younger Americans about whom we know at least some of their marital history, and assuming that their marriage rates in the future follow the trends of past birth cohorts, while also accounting for some degree of delay-and-catchup dynamics. The forecast period stretched further into the future for the ever-married share at age 45 because there are a greater number of birth cohorts under age 45 for which we have some observed marital history, enabling more confident forecasting into the future.

And in that future, marriage rates are likely to keep falling. The decline in marriage at age 25 may now be subsiding, but the effects of past delays will continue into older ages. This means that plausibly, one-third of men and women who turn 45 in 2050 (those who are about 18 or 19 today) will not have married.

This will have dramatic consequences for American society. It points to long-term fertility declines being hard to prevent, since marriage is a major factor shaping fertility behavior. These trends may also result in a whole slew of adverse outcomes as people age, including increased loneliness and isolation. The benefits of marriage for individuals and society are considerable, and thus the costs of falling marriage are, too.

Lyman Stone is a Research Fellow at the Institute for Family Studies and Chief Information Officer of the population research firm Demographic Intelligence.