Highlights

- Research suggests that multigenerational living could improve mental well-being for older members of the community. Post This

- The health and well-being risks of aging are exacerbated by living alone. Post This

- Many older Americans have no biological children, which means that they may have limited alternatives to living alone. Post This

Americans are having fewer kids, living longer, and living alone. Older people who live alone are more likely to suffer from loneliness and depression and have higher mortality rates. How might we better support older members of the community who are living alone but may not want to? One potential solution is to promote multigenerational living arrangements, where younger adults (ideally family or friends) live with people from older generations. Research suggests that multigenerational living could improve mental well-being for older members of the community. Living alone, in contrast, is associated with depression, loneliness, and higher all-cause mortality. The concept of intergenerational living, however, faces significant social and cultural obstacles and is only beneficial in certain circumstances.

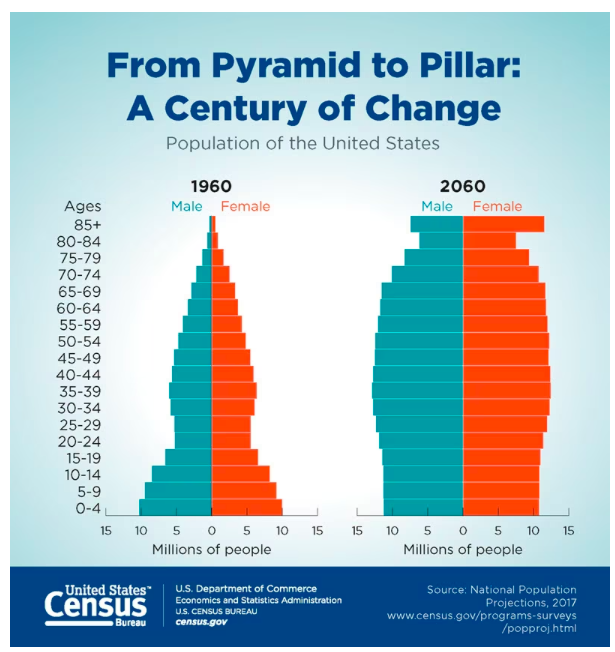

From Pyramid to Pillar

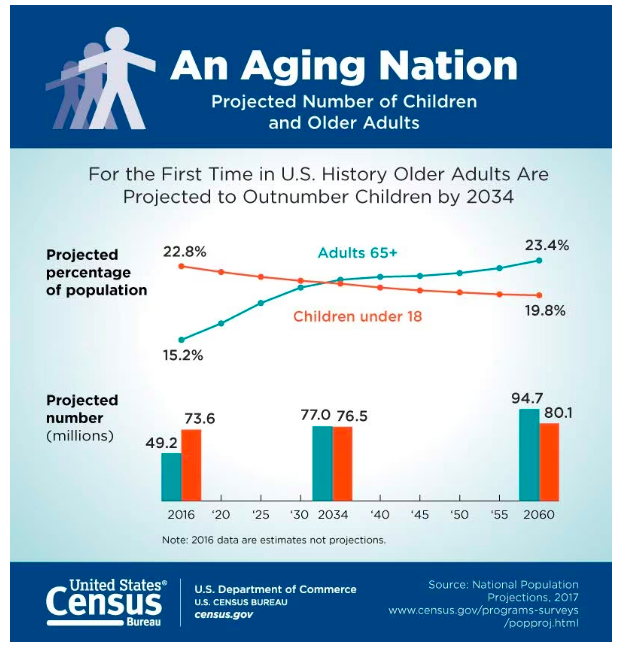

The U.S. Census Bureau notes that in 2020 about 16.8% of the population (1 in 6 people) in the United States were aged 65 or over. That’s up from 13% in 2010. In 2034, older Americans (65 years or older) will for the first time outnumber children under the age of 18. The 2018 US census infographic below provides an illustration of the scope of this demographic shift.

There is much that is concerning about an aging population, but we do well to attend especially to the increasing number of older Americans who are living alone. A 2019 Pew Research Center survey found that 27% of adults aged 60 and older in the US are living on their own. This percentage is more or less on par with Canada and Europe but far above the global average of 16% (based on 130 countries studied). Older women are much more likely than men to live alone. Roughly one-third of women ages 60 and older live alone in North America, compared with one-fifth of men.

Many older Americans have no biological children, which means that they may have limited alternatives to living alone. Of the 92.2 million adults aged 55 and older in 2018, 15.2 million (16.5%) were childless. Childless adults are particularly likely to live alone, according to the Census Bureau, as they “are also less likely to have gotten married and, therefore, less likely to be living with a spouse.”

The Risks of Living Alone in Later Life

Older people are already more vulnerable to depression and loneliness and have a higher mortality risk. The Surgeon General’s recent report on loneliness noted that older adults are among those with the highest prevalence of loneliness and isolation.

The health and well-being risks of aging are exacerbated by living alone. That is to say, living alone is associated with an increased mortality risk, and older men and women who live alone are more likely to suffer from depression, loneliness, and decreased mobility. Interestingly, living alone is not directly associated with poor cognitive function, though social isolation is. One study notes that those who live alone are “more likely to experience greater social isolation and smaller social networks, which are predictive of a negative impact on cognitive function.”

The relationship between living alone and well-being is complicated by the reasons why older people live alone. For example, we know that people who move from living with others to living alone because of divorce or widowhood are more vulnerable. There may be others who have strong family relationships, good health, and very high levels of social connectedness but who also choose to live alone.

But living alone in later life can put people in a vicious cycle. Older people often have less agency to change their living arrangements due to declining health and the experience of ageist stigma. It may be harder to find a housemate in later life than in early adulthood. For those who want to live with others, the options may be limited.

The Value of Multigenerational Living

Promoting opportunities for multigenerational living is one solution to this problem. Multigenerational living is, in at least some cases, associated with higher life satisfaction and decreased mortality. Multigenerational living arrangements also facilitate caregiving for older adults. Benefits appear to be strongest when older people are living with family, and not just their children but also their grandchildren. It stands to reason that occupying the social role of a grandparent gives older people meaning and purpose.

Multigenerational living may not always be of benefit to older members of the community and may even come with risks. Living in a multigenerational household, for example, was a risk factor for contracting COVID-19 during the pandemic. But we should also bear in mind that lonely people had higher rates of anxiety, depression, and suicide during the pandemic. Other studies have found no increase in short-term illness risk in multigenerational households.

Opportunities and Obstacles

Multigenerational households are becoming more common. Part of this is a function of an aging population. It is also related to rising housing prices and the difficulty of younger people entering the property market.

There is also an intentional focus in some jurisdictions on creating opportunities for multigenerational living. Experimental communities bringing together college students with older adults have been trialed in Canada, California, and the Netherlands, with mixed results.

A range of social factors make it difficult to promote such households. Some may live alone for complex personal reasons and may be averse to forming households with younger people. North American culture is also more individualistic than Asian cultures that emphasize filial piety and have a stronger cultural expectation that younger people will look after their older family members.

The shrinking number of young adults also presents a problem for multigenerational households. For the childless, the best form of multigenerational living—living with children and grandchildren—is not an option.

If multigenerational households have modest to significant benefits for older Americans, we should seek to make multigenerational living arrangements a viable option. Governments should consider financially supporting multigenerational living such that families have the opportunity to live together if they wish to do so. Younger generations ought to consider whether they can live closer to, if not with, their older family members. Older members of the community deserve meaningful options rather than diminished agency and attention in later life. Facilitating multigenerational living is one way to meet this social obligation.

Xavier Symons is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the Human Flourishing Program at Harvard University.