Highlights

- Married individuals consistently reported better mental health—fewer days of depression, anxiety, worry, and loss of interest in life—throughout the pandemic than their unmarried counterparts. Post This

- Also, mental health among married individuals did not decline nearly as much in response to deteriorations in the labor market and job prospects as it did among their unmarried counterparts. Post This

2020 set the record for the year with the most negative emotions, according to Gallup. While everyone went through the same storm last year, and even though that storm rages on, not everyone experienced the trials and tribulations in the same way.

In a recently-released study published in Social Science Quarterly, we use data from the Census Household Pulse Survey and find that married individuals consistently reported better mental health—specifically, fewer days of depression, anxiety, worry, and loss of interest in life—throughout the pandemic than their unmarried counterparts. Moreover, mental health among married individuals did not decline nearly as much in response to deteriorations in the labor market and job prospects as it did among their unmarried counterparts.

Why might we see such benefits? For starters, marriage has often been linked with psychological benefits by conferring greater purpose and structure. Results like this also highlight the important economic advantages of marriage: sharing risk, sharing goods, and specializing in household tasks. For example, married individuals generally pool their income, so if one spouse is laid off, the household may still rely on some income from the other spouse. These benefits of marriage tend to increase with the wealth of the couple—something economists have called “collateralized marriage” to explain why wealthier individuals are more likely to be married today.

There’s no doubt about it—people who get married are different from those who do not. This is especially true today, when marriage is more of an “option” for both men and women than ever before. Researchers have long been interested in studying how marriage affects mental health, but it has been difficult to isolate the effects of marital life from the preexisting differences between individuals who seek out marriage and those who do not.

Our study addresses these differences among married and unmarried individuals in two ways. First, our data allowed us to control for a wide array of characteristics: income, education, sex, race, and age. Second, we explored how changes in mental health responded to changes in income induced by state-level layoffs.

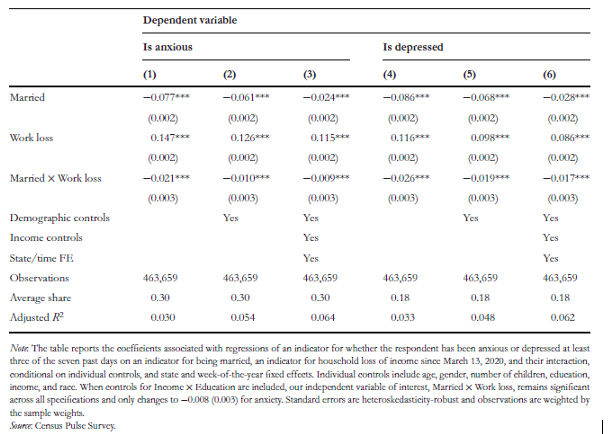

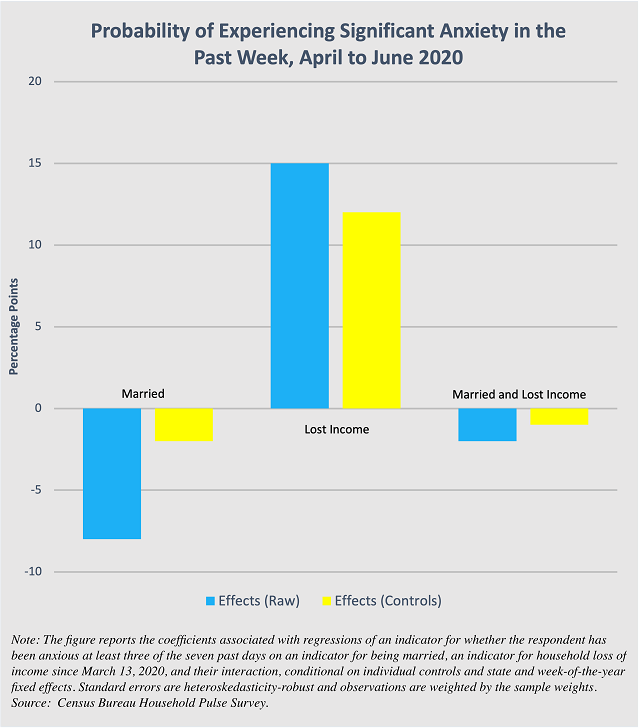

Compared to unmarried respondents, we find that married respondents were 2.1 percentage points less likely to report feeling overwhelmed by anxiety following a decline in household income. Since those experiencing an income loss were 14.7% more likely to feel anxious in general, marriage itself seemed to protect against 14.3% of income declines. These results are illustrated in the figure below, comparing the coefficients from our raw specification to those with the full set of controls (i.e., demographics, income, and state and time fixed effects).

If we investigate these effects by comparing respondents with a college degree to those without, the results are striking. Under our strictest specification, we find that married college graduates were 2.3 and 2.7 percentage points less likely to feel anxious and depressed (respectively) following a decline in income, compared to their unmarried, college-educated peers.

The results change when we focus on those without college degrees. While we find that married adults without a college degree were 2.9 and 3.5 percentage points less likely to report anxiety and depression (respectively), our results show no significant protective effect of marriage for these households if they have lost work-related income. One explanation behind these results might be that those without a college degree were simply so adversely affected over the pandemic that it overwhelmed any potential protective effects.

Evidently, not everyone benefits the same from marriage. For example, many individuals in abusive relationships experienced even harsher treatment during the pandemic with more people unemployed or trapped at home.

While we cannot distinguish the quality of a marital relationship from our data, we explored how the protective effects of marriage to income declines might vary across different demographic brackets. We found that the mental health of white, working-class men is most likely to be fortified by marital life. For example, although men in general are more likely to feel anxious following a loss of work, married men were 2 percentage points less likely to feel frequent anxiety in this situation, relative to their unmarried counterparts. Considering that economists have documented an increase in deaths of despair for men aged 15-55 during the pandemic, marriage seems to be an important barrier against such tragedies.

Married women also reported better mental health when compared to unmarried women. These benefits seem especially strong when we focus on serious mental health issues like depression. For instance, the likelihood that a married woman reported frequently feeling depressed following a loss of work-related income was 1.4 percentage points lower than for an unmarried woman in the same circumstance.

What do these results about the protective effects of marriage imply for children? While time will tell, they suggest that children with the benefit of both parents fared better during the pandemic than their counterparts who had only one parent present. If one parent was laid off, he/she could reallocate time to child care, while the other parent continued working. If only one parent is available, then he/she could be forced to take time off, especially since the child care sector was hit so hard.

In sum, our results confirm the intuition that marriage protects individuals in times of distress—whether with additional financial or emotional resources. This protective effect of marriage, however, varies by demographic group. Marriage seems to have the strongest effect when protecting the mental health of white, working-class men.

Christos A. Makridis is a research professor at Arizona State University and an adjunct scholar at the Manhattan Institute. Clara E. Piano is an assistant professor at Samford University.

Appendix