Highlights

- Couples where the husband’s total income was more than $38,000 per year greater than his wife’s income were the least likely to divorce by 2021. Post This

- More than half of all marriages in the U.S. are now dual-earner marriages and the share of women who earn as much as or significantly more than their husbands has roughly tripled over the past 50 years. Post This

- The negative effect of a husband’s higher income relative to a wife’s income on the chances of divorce has not changed since the 1990s. Post This

Research in evolutionary psychology suggests that financial prospects are more of a priority for women than men when choosing a spouse, and that this is the case around the world.1 There is also evidence for the U.S. that marriages are less stable when the wife out earns the husband, especially when the husband is unemployed or underemployed.2 Yet recently, The Wall Street Journal reported that while in the past marriages where the wife earned more than her husband were more likely to end in divorce, this was no longer the case. The article cited research from sociologists at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, which found that while couples married in the late 1960s and 1970s were more likely to divorce if the woman earned more, this was no longer true for such couples who married in the 1990s. The authors argued this was a result of a cultural change away from norms favoring the male breadwinner family model toward norms favoring more egalitarian dual-earner marriages.

It is true that more than half of all marriages in the U.S. are now dual-earner marriages and the share of women who earn as much as or significantly more than their husband has roughly tripled over the past 50 years. According to the PEW Research Institute, in 1972 the wife was the primary or sole breadwinner in only 5% of marriages, but by 2022, this had risen to 16% of marriages. There was also a decline in marriages where the husband was the primary or sole provider, from 85% in 1972 to 55% in 2022, and an increase in marriages where both spouses earned about the same, from 11% in 1972 to 29% of marriages in 2022.

But is it accurate to state that a wife out earning her husband is no longer associated with an increased chance of divorce?

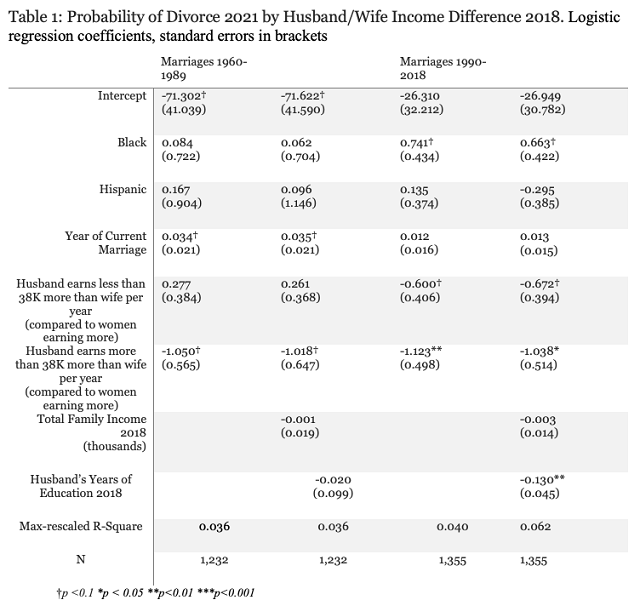

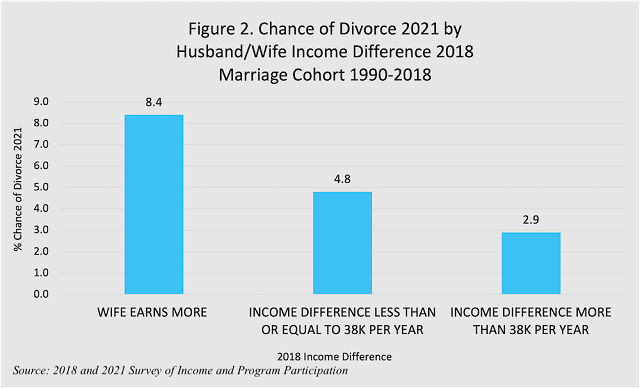

To investigate this, I examined data from the longitudinal cohort of the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) for 2018-2021. I looked at the effect of the difference in income between husbands and wives in 2018 on divorce in 2021 for people from two groups—those married from 1960 to 1989, and those married from 1990 to 2018. Figure 1 shows that for those married between 1960-1989, couples where the wife had a higher income than the husband had a 3.3% chance of divorce by 2021; couples where the husband’s income was $38,000 or less more per year than the wife’s had a 4.4% chance of divorce by 2021; and couples where the husband’s income was more than $38,000 per year greater than his wife’s had a 1.2% chance of divorce ($38,000 was the midpoint of the range of positive husband/wife income differences in 2018). Thus, couples where the husband’s total income was more than $38,000 per year greater than his wife’s income were the least likely to divorce by 2021.

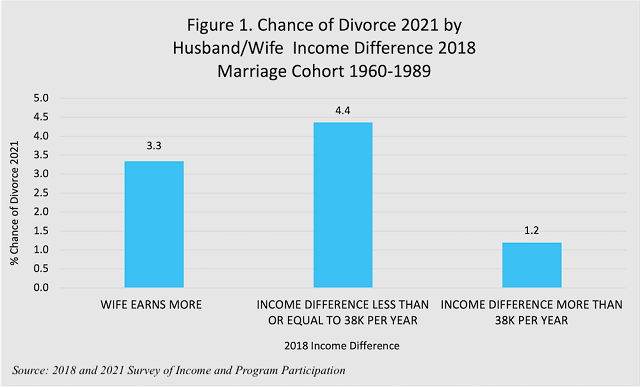

Figure 2 shows that for those married between 1990 and 2018, the chance of divorce by 2021 was higher than it was for couples married from 1960 to 1989, which is to be expected since most divorces occur in the early years of marriage, and those who married from 1960 to 1989 had been married at least 29 years by 2018. For the more recent marriage cohort, those couples where the wife’s income was greater than the husband’s had an 8.4% chance of divorce by 2021; couples where the husband’s income was $38,000 or less more per year than the wife’s had a 4.8% chance of divorce by 2021; and couples where the husband’s income was more than $38,000 per year greater than the wife’s had a 2.9% chance of divorce by 2021. Thus, men whose income was more than $38,000 per year greater than their spouse’s income were the least likely to be divorced by 2021, and they were significantly less likely to be divorced than men in couples where the wife’s income was higher (see Table 1).3 Other analyses showed that the effects of the husband/wife income difference on the chances of divorce did not differ significantly by marriage cohort, suggesting that the negative effect of a husband’s higher income relative to a wife’s income on the chances of divorce has not changed since the 1990s.4

These findings contradict those reported in The Wall Street Journal that when wives earn more than their husbands, they are no longer more likely to divorce. Those couples least likely to divorce were those where the husband had a much larger income than his wife, which includes couples where the wife does not work outside the home.

It seems that the traditional male breadwinner family is still very much a reality in the U.S., and those couples where the wife has a higher income than the husband still have a greater chance of divorce than couples where the husband has a substantially higher income. This is not only true in the United States. In highly egalitarian Sweden, a higher share of income earned by the wife creates an increased risk of divorce, per one study, and another study found that even an unexpected windfall (winning the lottery) leads to a greater chance of divorce for female winners and a lower chance of divorce for male winners. These results suggest that the spouse who provides the most financially in the marriage matters differently to husbands versus wives, and they are consistent with the claim that women still value the financial prospects of a spouse more than men do.

Rosemary L. Hopcroft is Professor of Sociology at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. She is the author of Evolution and Gender: Why it matters for contemporary life, (Routledge 2016) and editor of The Oxford Handbook of Evolution, Biology, & Society (Oxford, 2018).

1. Buss DM. (1989). Sex differences in human mate preferences: evolutionary hypotheses tested in 37 cultures. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 12(1):1–14; Buss, D. M., & Schmitt, D. P. (2019). Mate preferences and their behavioral manifestations. Annual Review of Psychology, 70, 77-110.

2. Teachman, J. (2010). Wives’ economic resources and risk of divorce. Journal of Family Issues, 31(10), 1305-1323; Killewald, A. (2016). Money, work, and marital stability: Assessing change in the gendered determinants of divorce. American Sociological Review, 81(4), 696-719.

3. In the model with all respondents for both marriage cohorts, the dummy for husbands earning 38k or less more is not significant, while the dummy for husbands earning more than 38k more is significant ( p < 0.01).

4. The SIPP is a large-scale sample survey of the civilian, noninstitutionalized population of the United States fielded by the U.S. Census. SIPP data requires specialized software and weighting to account for the fact that it uses a multistage stratified sample of the U.S., but when analyzed correctly gives information for a representative sample of the U.S. population, so these results apply to the U.S. as a whole. To do the analysis, I matched husbands and wives who were married and living together in 2018 and who had never been divorced and determined the difference in their incomes in 2018. Then, I examined if those married and living together in 2018 were divorced by 2021, and if this was associated with the 2018 difference in income between husband and wife. I also controlled for race, ethnicity, and year of marriage (see Table 1 in the Appendix). The SIPP measure of income I used is a comprehensive one that includes income from all sources, not just earnings from a job, including wages, rental property, government programs, pensions, annuities, trust funds, and business income so it may include losses as well as gains. As such, it is a very comprehensive measure of the financial resources each spouse brings to a marriage.

Appendix