Highlights

It’s election season, and so, of course, we’re talking about sexual misconduct. On the Republican side is a front-runner who matter-of-factly admits to an extramarital affair. On the Democratic side is a front-runner whose husband has been accused of multiple sexual improprieties (and who hasn’t always matter-of-factly admitted to them).

Sexual misconduct is also often discussed in the context of religion, perhaps to give journalists something to write between elections. So why not put all three topics forbidden in polite company—sex, politics, and religion—into one blog post?

I’ll focus on extramarital sex using a question from the General Social Survey (GSS): “Have you ever had sex with someone other than your husband or wife while you were married?” Obviously, this is only one type of sexual misconduct, and it does not apply to people who have never been married. Still, it’s misconduct that most Americans disapprove of.

The GSS first asked this question in 1991, and it’s been on each GSS survey (fielded every two or three years) since then. Pooling the data from 1991 to 2014, 13.2% of the GSS respondents who had ever been married reported having had extramarital sex. There’s a strong gender effect here, with 16.5% of men acknowledging it but only 10.7% of women. There is also an age effect, with older people reporting extramarital sex more often; this is to be expected because they have had more years to have ever strayed.

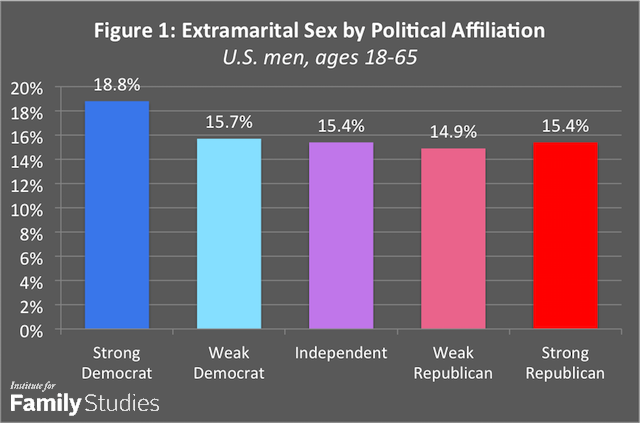

In analyzing the association between extramarital sex and politics and religion, I’ll limit my analyses to men between ages 18 and 65 interviewed in the GSS. Let’s start with politics. As shown in the first figure, there is some variation in extramarital sex by political identification. Who is most likely to have cheated in marriage? Strong Democrats. A full 18.8% of them have stepped out of their marriage at some point compared to only 15.4% of the strong Republicans.

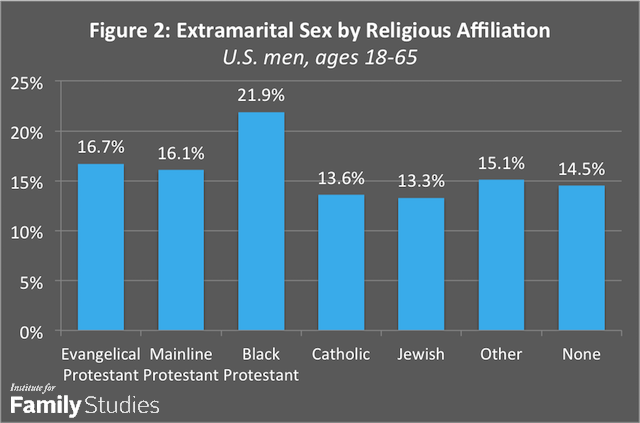

Analyzing the religion-cheating link is more complicated, since religion has multiple dimensions. Perhaps the most straightforward one is religious affiliation; i.e., does someone think of themselves as belonging to a particular religion? A commonly used framework for analyzing American religions is the RELTRAD classification, which categorizes seven distinct religious traditions in the U.S. As shown in the figure below, rates of extramarital sex vary across these traditions. At the low end are Jews (13.2%) and Catholics (13.6%). At the high end are black Protestants (21.9%). In between are evangelicals, mainline Protestants, members of other faiths, and the religious “nones” (those with no religion).

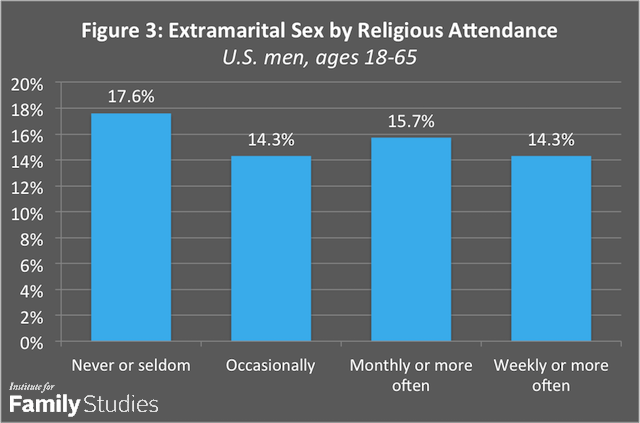

Based on just affiliation, religion does not make much difference in men’s odds of having extramarital sex. But, as is often the case, this changes when we move to other measures of religion. When it comes to attending religious services, a little religious involvement goes a long way. Close to 18% of men who rarely if ever attend church services have engaged in extramarital sex. Men who attend services weekly (14.3%), monthly (15.7%), or even just yearly (14.3%) show lower rates.

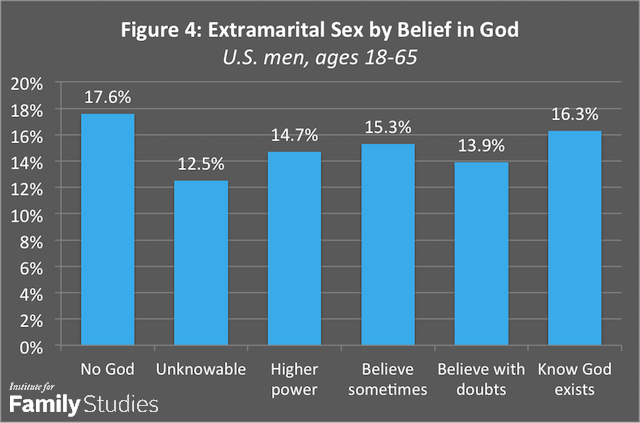

An uneven pattern emerges when we look at extramarital sex and various religious beliefs. Men who do not believe in God have the highest rates of extramarital sex (17.6%), but those who are certain that God exists have the next highest (16.3%). At the low end are those who think it is not knowable whether God exists (12.5%), and the remaining categories of belief are at about 14% and 15%.

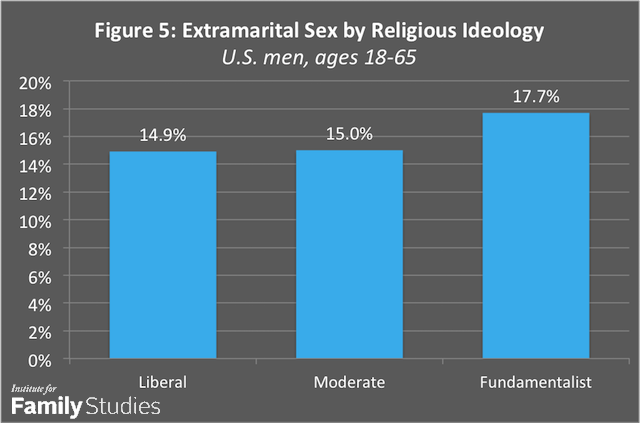

When it comes to religious ideology, liberals and moderates have modestly lower rates (14.9% and 15%) than religious fundamentalists.

However, men who view the Bible as just a book of fables have higher rate of extramarital sex (16.1%) compared to those who view it as the inspired word (15.7%) or the word of God (14.3%).

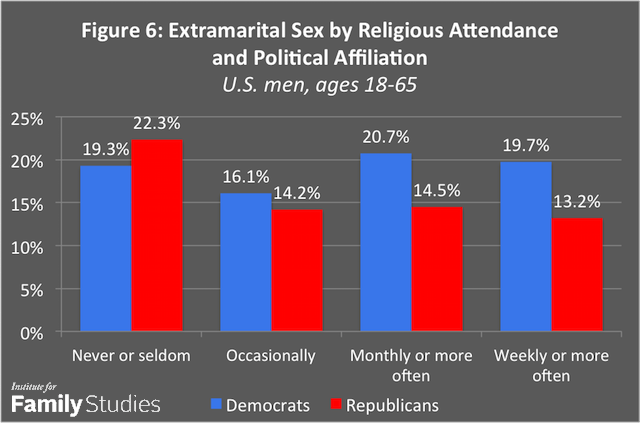

When I set out to write this blog post, I was going to look at politics and religion separately and leave it at that. But as I started analyzing the data, I wondered if there is an interaction between them. That is, does the relationship between religion and extramarital sex vary by political affiliation? To test for this interaction, I plotted the relationship between religious service attendance and extramarital sex separately for men who identify themselves as strong Democrats versus those who are strong Republicans. As you can see in the next figure, there is something going on here. Among strong Democrats, there is little relationship between attending religious services and extramarital sex. Non-attenders have high rates (19.3%) as do frequent attenders (19.7%). Among Republicans, however, service attendance means much lower rates of extramarital sex. Who is most likely to have extramarital sex? Republicans who don’t go to church (22.3%). Who is least likely? Republicans who go to church often (13.2%)

How do we interpret this relationship between religion, politics, and extramarital sex? To take a more in-depth look at the interaction between religion and politics, I estimated a logistic regression equation that had politics, religion, and the interaction between them predicting extramarital sex. The interaction term is significant. It remained significant, and about the same size, when I controlled for age, education, gender, and region. However, when I controlled for race, the magnitude of the interaction term dropped by about half and became statistically insignificant.

In laymen’s terms, the relationship between religious service attendance and extramarital sex does vary by politics, as shown above, and the explanation appears to have something to do with the different racial composition of the two political parties. Among the strong Democrats that I’ve been analyzing (i.e., men between 18 and 65), a full 32% are black. Among strong Republicans, just 2% are. Why does controlling for race nullify the interaction between political affiliation and religious attendance? I don’t know. It could be due to several things. Maybe religion affects sexual behavior differently across race. Or maybe politics affects sexual behavior differently across race. Or maybe the meaning of race itself varies by political affiliation. Or by religious affiliation. Maybe something else. We’re inching our way to a possible three-way interaction: politics by religion by race, and those are difficult to tease apart in a full journal article, let alone a humble blog post.

Now a couple of caveats. The analyses above are simply descriptive. Stronger statements about possible causality would require more sophisticated multivariate models. Also, it’s possible that people reply differently, more or less honestly, to questions about extramarital sex as a function of their politics and/or religion. Maybe Christians are less likely to admit to doing it, or, conversely, maybe Christians are more likely to “confess” their wrongdoings to a survey-taker. Finally, I’ve assumed that religion influences sexual behavior, but the reverse could equally be true. Maybe someone engaged in extramarital sex would be less motivated to be involved in religion.

These qualifications notwithstanding, the analyses here give us a better sense of the social patterning of extramarital sex. These patterns roughly fit the political actors described at the start of this post. Donald Trump is not an active member of a church, and so he fits the profile of Republicans who have affairs. Bill Clinton is perhaps more active in his faith, but it hasn’t seemed to change his sexual behavior much, as seems to be the case with Democrats.

Bradley Wright is an associate professor with the Department of Sociology at the University of Connecticut. He blogs at brewright.com on spirituality, well-being, and data. Follow him on Twitter @bradley_wright.