Highlights

- An overwhelming amount of evidence now exists that regular engagement with porn is a risk factor for poor relationship health. Post This

- Religiosity, in particular, changed the nature of the relationship between pornography use and relationship stability, while some of the effects appeared to also be stronger for men. Post This

- Pornography use appears to be linked to less relationship quality, especially relationship stability. Post This

Getting “lost in the weeds” is a common expression that captures the idea of getting so focused on the minute details of an issue that the bigger picture gets lost. Pornography and its association with relationship health is one such topic where scholars have gotten lost in the “weeds” of increasingly complex and seemingly contradictory findings. Finding a clear and concise storyline in these research findings has become more difficult. While many states and other governmental agencies have begun to discuss and enact policies signaling the dangers of pornography use for both children and adults, scholars, clinicians, and other experts remain decidedly mixed on whether we can really say anything at all about the relationship effects of pornography. This has led some to argue that too many competing factors are at play to suggest pornography is addictive, harmful, or a risk to healthy relationship formation.

To that end, experts have noted that a long (and growing) list of contextual factors may alter, diminish, or even remove any potential consequences of viewing pornography on a romantic relationship. This list includes whether the person viewing pornography believes they are addicted to it, the content or type of pornography being viewed, whether pornography is viewed alone or with a romantic partner, whether masturbation accompanies pornography, and the religiosity of the person. In each case, experts have argued that these factors may be the reason any negative associations are found between pornography and well-being. To make any blanket statement about the negative or positive outcomes of porn use, they argue, simply ignores an ever-growing web of factors that may make the influence of pornography so personalized that social science will never be able to make clear conclusions. The debate has become so convoluted that some experts in the area have made passionate and empirically-backed pleas to simplify future research and avoid the temptation to “overcontrol” pornography research into the ground by trying to consider a dozen factors at once.

The net result of these increasingly complex studies is that it is difficult for the general public, let alone policymakers, to get a clear understanding of how pornography affects the health of romantic relationships. It was against this backdrop of increasing complexity and confusion that we sought to try to dig into the heart of this issue and understand if pornography use does, in fact, have any effect on relationship well-being.

In a recent study, we utilized a large U.S. sample of over 3,500 people in committed relationships and explored how pornography was associated with relationship quality. This large dataset had a few advantages over previous data used in the field. First, it included detailed and precise measures of pornography use. By asking direct questions about participants’ viewing habits tied to very specific types of material, we were able to examine both their individual pornography use across both traditional mainstream pornography and more aggressive forms (for example, pornography that involves physical violence or forced sex). In this study, we were able to examine the content of pornography used and if any associations found were changed after considering gender, whether the individual believed they were addicted to porn, and how religious they were.

There are two ways to interpret our findings. In keeping with the current dialogue in the field, one way would be to acknowledge that there is a complex web of interactions between pornography use, gender, belief regarding addiction, and religion. We found that to some extent, each of these factors altered the negative relationship between pornography and relationship quality. Yet there is also a simple message that emerged from our findings: pornography use appears to be related to negative indicators of relationship well-being regardless of these other factors.

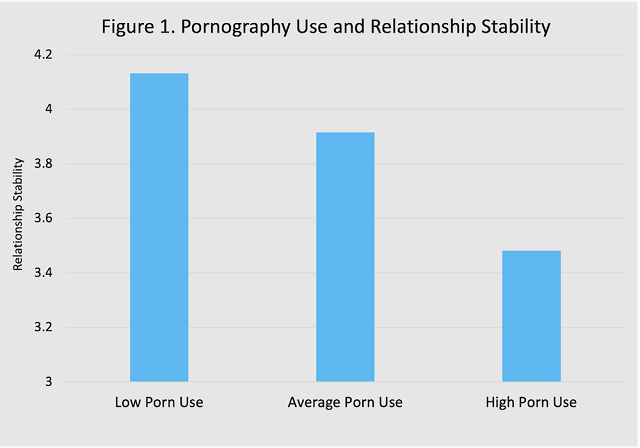

Take Figure 1, for example, which shows the simple relationship between relationship stability and pornography use. When isolated, this trend appears very clear and strong in our data. As higher pornography use was reported, lower relationship stability was also reported.

Source: B. Willoughby and C. Dover, "Context Matters," The Journal of Sex Research, Nov. 2022.

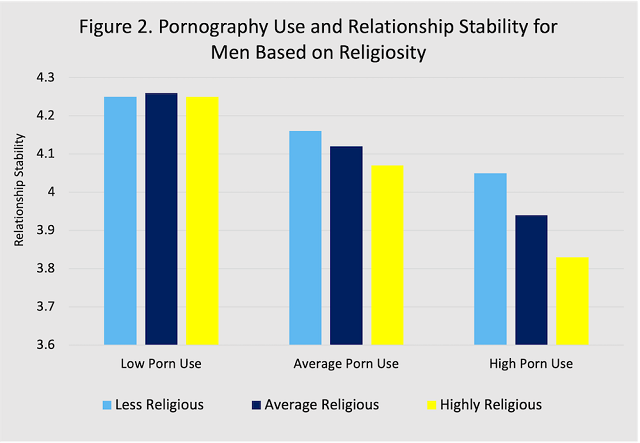

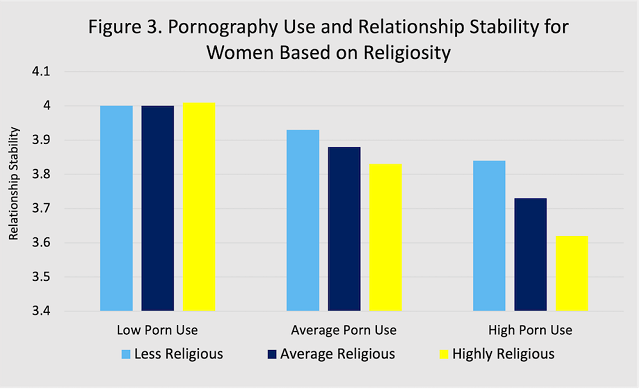

Figures 2 and 3 show this same association, but with differing levels of religiosity and gender factored in. In our study, we found that religiosity, in particular, changed the nature of the relationship between pornography use and relationship stability, while some of the effects appeared to also be stronger for men. In other words, it could be argued that the association between pornography use and relationship well-being in this study depended on one’s gender and level of religiosity. Figures 2 and 3 clearly illustrate that the drop in relationship stability appears to be stronger for those who are more religious for both men and women.

Source: B. Willoughby and C. Dover, “Context Matters,” The Journal of Sex Research, Nov. 2022.

But look at the figures again. While the pattern may become more pronounced for the highly religious, the same basic downward trend in relationship stability is still there for both men and women and for people of all levels of religiosity.

Source: B. Willoughby and C. Dover, “Context Matters,” The Journal of Sex Research, Nov. 2022.

The largest takeaway from our results is a simple yet sometimes overlooked aspect of the research on pornography. Just because a negative relationship becomes more or less negative when considering other contextual factors shouldn’t diminish the fact that the relationship is negative. While we found many interactions between different variables that suggested a range of changing effects, almost all of them were negative to one degree or another. And while we agree with our colleagues that the research is complex, we also found something basic and consistent: pornography use appears to be linked to less relationship quality, especially relationship stability. Negative effects tied to pornography do not exist solely because someone is religious, or a certain gender, or thinks they are addicted to porn.

A simple story does appear to exist in the scholarship: for the best chance of a healthy and long-term romantic relationship, trying to avoid using pornography is key.

While our study focused mostly on gender, perceived addiction, and religiosity, some scholars are beginning to note this same issue when exploring other factors sometimes believed to be contributing to a so-called spurious relationship between pornography and relationship well-being. In a recent letter to the editor at the Journal of Sex Research, prominent pornography scholar Paul Wright noted that while frequent masturbation is often discussed as the potential reason for why pornography is linked to lower relationship satisfaction, negative associations between pornography and satisfaction persist, even after controlling for masturbation rates. Wright argued that when considering the basic and simple relationship between pornography use and satisfaction, it is unlikely that masturbation is simply confounding the entire relationship between the two.

Whereas many experts and scholars seem content to debate what factors may reduce or change any negative association between frequent pornography use and relationship well-being, the fact remains that an overwhelming amount of evidence now exists that regular engagement with porn is a risk factor for poor relationship health. The patterns found in our study linking pornography to lower relationship stability have been found in other studies as well. Pornography use has been linked to an increased risk of divorce in large national datasets. Also, several meta-analyses have suggested that more pornography use is linked to lower relationship satisfaction. The evidence of a basic and clear negative relationship continues to grow.

There are a lot of weeds to sort through when it comes to pornography research. Yes, some pornographic content may have larger negative effects on individual and relationship well-being than others. Yes, being religious may compound the negative effects of pornography due to feelings of being out of step with one’s moral beliefs. Yes, men appear to be more impacted by watching pornography than women. However, these facts should not obscure the larger picture and trends in the research when it comes to relationship well-being and porn. A simple story does appear to exist in the scholarship: for the best chance of a healthy and long-term romantic relationship, trying to avoid using pornography is key.

Brian J. Willoughby, Ph.D., is Professor in the School of Family Life at Brigham Young University, and a fellow at The Wheatley Institute. Carson Dover is a graduate student in the School of Family Life at Brigham Young University.