Highlights

- In the online dating world, you are no longer just in competition with people in your social circles. You are also in competition with everyone in your city or region. Post This

- Online dating has become the premier way couples meet, now having a market share of nearly 40%, per a 2019 study. Post This

- The inequality of online dating gives the most attractive men enough options that there’s no incentive for them to commit, which also puts many women at a disadvantage. Post This

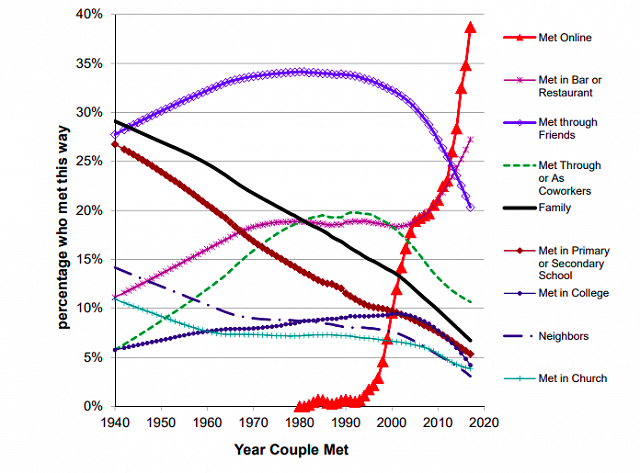

In recent years, online dating has become the premier way couples meet, now having a market share of nearly 40%, according to a 2019 study. All other ways of meeting besides bars and restaurants are in decline, as shown in the figure below:

Source: Rosenfeld, et. al. PNAS, Sept. 3, 2019.

Due to the inherently digital nature of online dating sites and apps, they provide significant amounts of hard data about how people behave on them. This allowed researchers to learn a great deal about the dynamics of online dating.

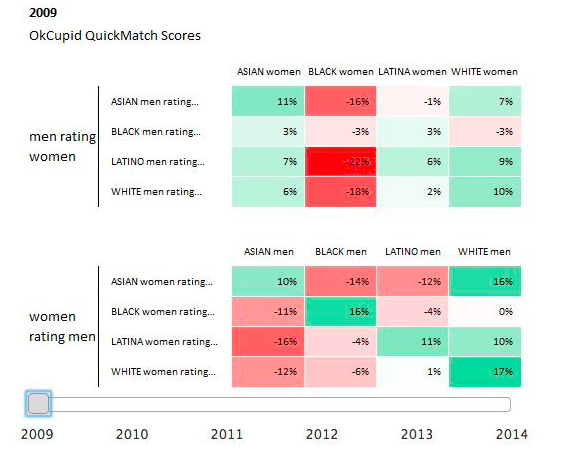

We now know, for example, many of the factors that affect subjective perceptions of attractiveness as revealed in user ratings or “likes.” At the macro level, this has revealed that people can be penalized based on their race. At the micro level, it seems that pictures with cats reduce the like rate of heterosexuals, while those with dogs raise their like rate.

It has also been discovered that the age of the men that women rate as most attractive scales roughly linearly with their own age, while men of all ages rate women in their early 20s as most attractive. And men tend to rate female attractiveness on a curve resembling a normal distribution, with most women rated around average, with fewer at the extremes. But women rate the vast majority of men as below average in attractiveness, and only a few as above average.

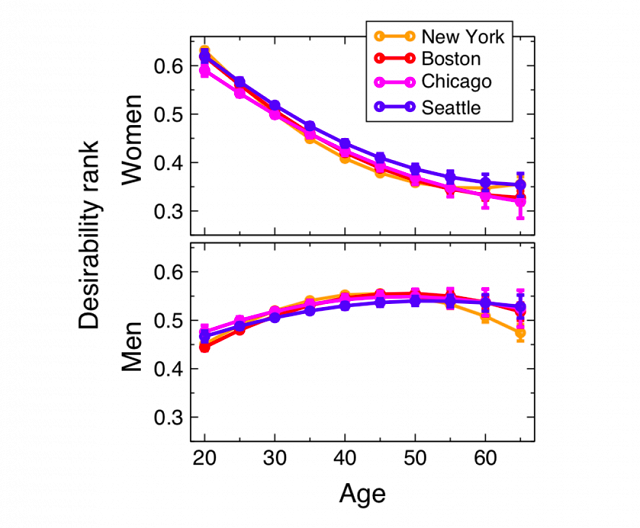

The dynamics of attraction also change over time, as a 2018 article on online dating in The Atlantic noted (the figure below, which shows how relative attractiveness changes by age, is from an academic study cited by the article, where researchers used Google’s page rank algorithm to rate the attractiveness of men and women on an undisclosed dating site in four cities). On average, users rate women as more attractive than men during their 20s, but in their early 30s, this reverses. From that point on, users rate men as more attractive than women on average.

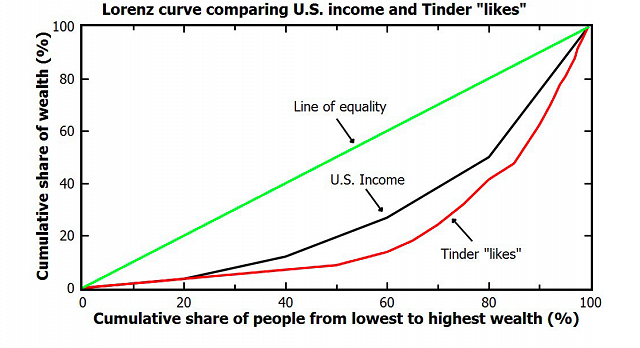

These sites also generate significant levels of inequality, especially for men. One analyst found that “like inequality” for men on Tinder is higher than income inequality in the United States (he created the chart below). An analyst at Hinge found that women’s inequality on that site was roughly equal to the average income inequality for the world’s countries (a Gini coefficient of 0.376), similar to Western Europe. But men’s like inequality (a Gini coefficient of 0.542) would rate as the eighth most unequal country in the world in terms of income inequality.

Inequality may result from a process similar to globalization. Prior to globalization, economic markets in most goods and services were primarily domestic, or even local in nature. These markets each had their own champions, their own winners and losers. Globalization merged these into a single, global market. This had profound effects on winners and losers. A few of the best or cheapest competitors reaped significant gains while many former domestic champions or viable competitors lost out.

Online dating has had a similar effect. If not the actual globalization of dating, then it is at least the metropolitanization of it. Prior to online dating, men and women met each other primarily in physical spaces and through social circles in the real world: school, work, church, family, friendship circles, and neighborhoods. The markets were very fragmented. You could certainly meet someone outside of that, even intentionally, such as by looking at old-school personal ads in a newspaper, but the number of potential matches you could meet that way was very limited.

Because every school, neighborhood, church, etc. was in essence its own market, that meant they each had their own local marketplace winners. And people would often match up within that based on their relative value in the market.

But with online dating, all those old local relationships markets have been merged. Now everyone has access to a large number of singles throughout his or her area. That means in the online dating world, you are no longer just in competition with people in your social circles. You are also in competition with everyone in your city or region. It may be true that your pool of prospects is also bigger. But the dynamics of these global type markets have in practice tended to produce more extremes of winners and losers. (The extremely high levels of inequality for men in particular may also be driven by the highly-imbalanced gender ratios on these sites, with far more male than female users).

Online dating also skews very strongly towards appearance as an initial screening criterion. This is particularly true on today’s swipe apps like Tinder. Nobody has time to wade through all the singles listings in their area, and that tends to promote heavy filtering. And after setting filters like age, etc., the easiest and quickest thing to filter is looks. Apps like Bumble even severely restrict the amount of text you are allowed to put in your profile.

This benefits people who are very good looking but hurts those whose best qualities are in other areas. This is particularly the case for men, because while men do tend to find women attractive based on looks and age, women look at a much broader set of characteristics that don’t show as well in online dating apps.

In summary, online dating has a number of characteristics that work against most people. People are penalized based on things like cats in photos that might have nothing to do with them as people. It’s not great for people who are not very good looking. The sites also generate high levels of inequality, especially for men. This puts most men at a disadvantage. But the same inequality gives the most attractive men enough options that there’s no incentive for them to commit, which also puts many women at a disadvantage, too.

Lots of people did meet their spouse or significant other through online dating. If it’s a tool that works for you, there’s no reason not to use it. But especially for men who aren’t in the top 10 to 20% in looks, going back to the physical world and social circles of yesteryear may be a better option. Not only does this allow men to avoid the globalization effect of online dating, it also allows them to look for opportunities to let their best male attributes shine.

For example, when I wanted to ask my now wife to move from Indianapolis to New York to be with me, I invited her to attend a large event in Indiana where I was speaking. I wanted her to have the opportunity to see me stand up in front of hundreds of people and confidently and competently delivery a half-hour keynote address.

As with so many other things about being a man, from being a musician to having a great a sense of humor and being a great conversationalist, there’s no way to convey the reality or impact of something like public speaking through an online dating profile. In the online dating world, you are going to be judged overwhelmingly by your looks. In the real world, there’s more opportunity to convey who you really are and showcase your best attributes as a man (or a woman, for that matter). In a world of low marriage rates, those looking for a lasting relationship rather than a hookup should perhaps rethink the virtues of meeting people in the offline world again.

Aaron M. Renn is the publisher of the Masculinist, a newsletter about Christianity, masculinity, and the modern world. This article was adapted from “The Truth About Online Dating,” originally published in the Masculinist.