Highlights

- A sizable minority of women in the U.S. are using contraceptives despite not wanting to limit or delay childbearing. Post This

- About 25-35% of women are favorable towards permanent contraception for women who still want more children. Post This

- If these patterns hold in the real world, it’s likely that American women face a lot of pressure to conform to contraceptive norms regardless of their own fertility preferences. Post This

At the 1994 Cairo International Conference on Population and Development, a new global consensus formed around the idea that enhancing women’s individual health and rights was a more noble goal than controlling population growth. This then-new emphasis on reproductive autonomy had real life implications, e.g., the Indian Family Welfare Programme service stopped issuing its workers targets for contraceptive uptake. The new prevailing belief was that there was no need to push contraception because women who experienced empowerment in other walks of life could be trusted to make whatever contraceptive choice was right for them, without a push by the government.

So has the promotion of contraception stopped? After 30 years, do we now have a world where contraceptive use now matches individual reproductive goals?

Using data from the October 2023 Demographic Intelligence Family Survey, a twice-yearly survey of U.S. females ages 18-44, we reveal three facts that are odds with the idea that individuals are completely free to make their own reproductive choices.

- First, a sizable minority of women in the U.S. are using contraceptives despite not wanting to limit or delay childbearing.

- Second, many Americans hold attitudes supporting inappropriate contraceptive use (e.g., advocating sterilization for those who are unsure about their future childbearing goals).

- Our data do not prove that most women are still being pressured into using contraception, but they do introduce the possibility that pro-contraceptive norms may lead to excess use (and with it, excess side effects).

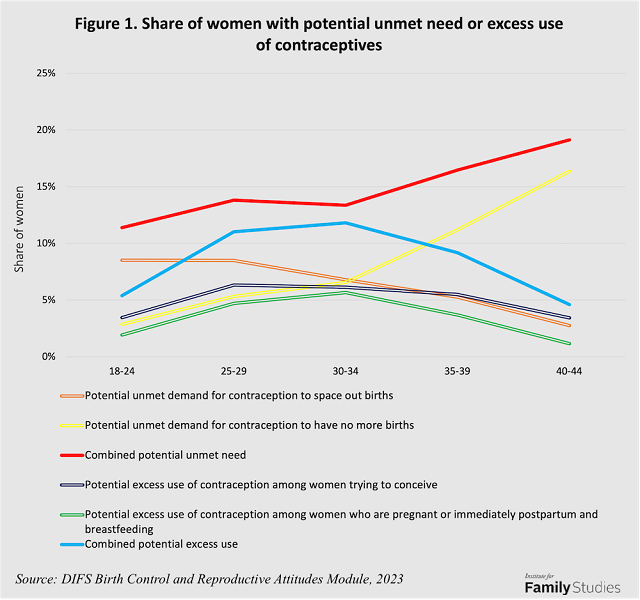

As figure 1 below shows, about 6% of women ages 25 to 34 are using contraceptives despite wanting to have a child soon, and another 5% are using contraceptives despite being pregnant or immediately postpartum and breastfeeding. This behavior isn’t necessarily contradictory: For example, condom usage may occur to prevent a sexually transmitted infection. Nonetheless, it shows that some women use birth control contrary to their reproductive desires. This same approach suggests that about 6% of women in this age range may have unmet need for contraceptives to end childbearing, and another 7% may have unmet need to space out their next birth. Thus, potential unmet need and potential excess use are similar in magnitude. And yet, the issue of excess use has not received the same kind of attention as women not using birth control when they want to stop or delay childbearing. Where could this “excess use” of contraception be coming from?

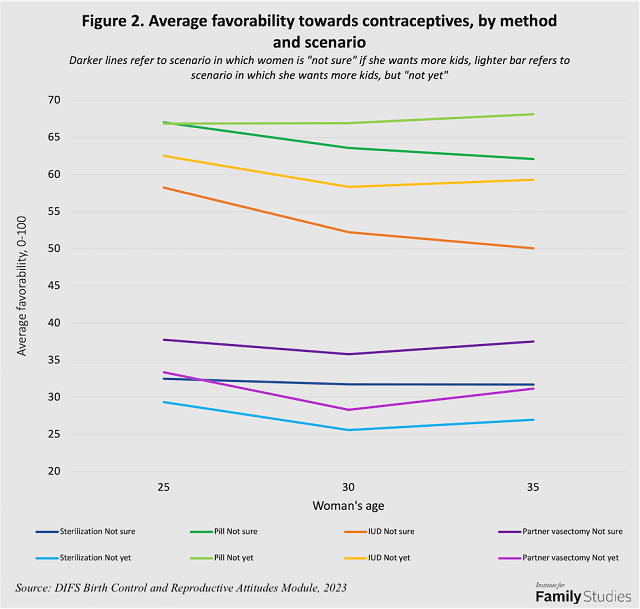

We also used the DIFS survey wave from October 2023 to explore attitudes towards contraception. Respondents were presented with a hypothetical scenario in which women of various ages (25, 30, or 35) and fertility preferences (e.g., not sure if they wanted more children, or wanted more but not yet) were presented, and respondents rated the appropriateness of various contraceptive options. Figure 2 below shows the average favorability women reported for each contraceptive option, by the hypothetical woman’s age and fertility preferences.

Several major facts stand out.

- First, American women are more favorable to reversible contraception (pills, IUDs) than either partner’s sterilization.

- Second, reversible contraception was more favored for women who wanted kids but “not yet,” while permanent methods were more favored for women who were “not sure” they wanted kids at all.

- Third, as women get older, others seem to think not being sure about having kids no longer justifies the use of reversible contraceptives. Instead, for older women, they tend to favor either permanent contraception or no contraception.1

These overall trends make sense, but may obscure the startling fact that about 25-35% of women are favorable towards permanent contraception for women who still want more children. A woman still who wants more children, but just not quite yet, (especially at just age 25) is not even remotely a good candidate for a tubal ligation.

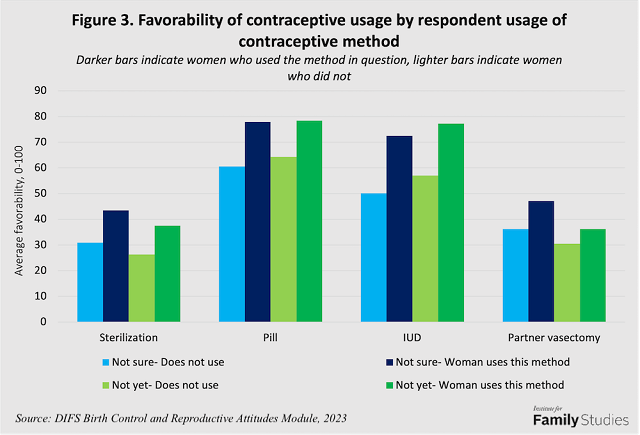

What drives women to ignore fertility preferences when making contraceptive recommendations? First, their own contraceptive choices. Figure 3 shows favorability of contraceptive methods by the scenario type (not sure vs. not yet) and whether respondents personally report using the method being asked about.

Regardless of method, respondents who personally used the method are about 10 to 20 points more likely to be favorable towards other women’s use of that method (the dark bars are higher than the light bars). More importantly, women’s own contraceptive usage is a much stronger predictor of their recommendations for other women than those other women’s actual fertility preferences (the contrasts between the blue-bar “not sure” scenario and the brown-bar “not yet” scenario are relatively modest within usage categories). In other words, women seem to decide what contraception to endorse, not based on what other women actually want as much as what they have decided is good for themselves.

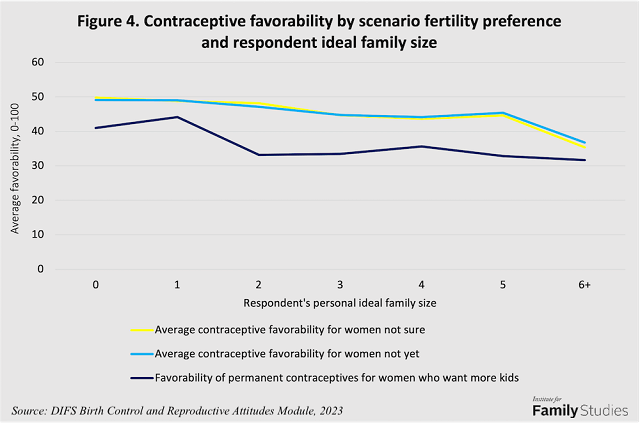

Second, women base recommendations on their own ideal family size rather than others’ fertility preferences. In Figure 4, the proportion of women favoring contraception declines as the respondent’s own ideal family size increases, but it does not vary across others’ preferences.

Turning to the extreme case of advising permanent contraception for women who do want more children, women with unusually low ideals (0 or 1 child) are much more likely to recommend this. In other words, low personal fertility preferences are associated with respondents explicitly advising “excess use” of permanent contraception. The idea that contraception can be good regardless of what women want did not end at the global conference in Cairo when the rhetoric shifted from population control to women’s empowerment. In the U.S., at least, low personal fertility preferences are associated with respondents explicitly advising “excess use” of permanent contraception.

Conclusion

In the United States today, many women are not using contraception even though, in theory, contraceptive usage is consistent with their family desires. This “unmet need” is widely studied and widely recognized as a possible public health concern.

Far less recognized is the also very-common issue of excess use: women using contraceptives which may not be appropriate for their situation. In this article, we showed that possible excess use is not atypical, and is most pronounced among women ages 25-34, during the key years shaping whether or not women achieve their fertility goals. Our findings are consistent with other recent publications pointing to significant “unwanted family planning” in many countries.

Contrary to the idea of empowering individual choice, we show that women’s favorability ratings for contraception largely ignore the actual reported preferences of other women they are putatively advising. Rather, in the DIFS survey, the main factors predicting how women advise other women about contraception are their own current contraceptive usage and their own desired family size.

The real world may differ from surveys. But if these patterns do hold in the real world, then it’s likely that women in America face a lot of pressure from wider society (including other women) to conform to contraceptive norms regardless of their own fertility preferences. This is a serious issue, so much so that the UNFPA’s 2023 State of World Population Report actually highlighted contraceptive pressures and advice at odds with fertility preferences as a globally significant public health issue. Even as policymakers continue to ensure that women who want non-abortive contraceptives are not unduly restricted from them, it seems they should also work to address the issue of American women being pressured into using contraceptives they may not want (especially methods that cannot be reversed, like tubal ligations, partner vasectomies, or IUDs).

Lyman Stone is a Research Fellow at the Institute for Family Studies and Chief Information Officer of the population research firm Demographic Intelligence. Laurie DeRose is a senior fellow at the Institute for Family Studies, Assistant Professor of Sociology at the Catholic University of America, and Director of Research for the World Family Map Project.

1. This could have two explanations. Some respondents may presume that older women without children are infertile or menopausal and so do not need contraception. Other respondents may believe that women at all interested in childbearing as they get older should forego contraception.