Highlights

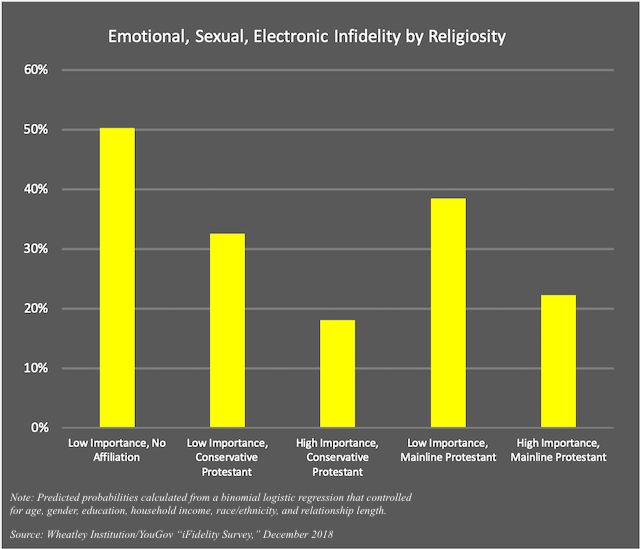

- Those with no religious affiliation and low personal religious importance were about 30 percentage points more likely to be unfaithful to a spouse than either Conservative or Mainline Protestant individuals with high personal religious importance. Post This

- When granted high importance in our lives, faith can serve as a type of watch tower, warning us of the threats that wait beyond the walls of our family. Post This

As documented in the New York Times, “national surveys indicate that 15% of married women and 25% of married men have had extramarital affairs” with occurrences “about 20% higher when emotional and sexual relationships without intercourse are included.”1 It is clear that infidelity is penetrating the “walls” surrounding marriage relationships today. In our online world, opportunities for infidelity are as close as our fingertips.

In an analysis of The Wheatley Institution’s 2018 iFidelity survey, a nationally representative dataset, we found that a combination of flirting in real life with someone other than one’s spouse, following an old flame online, and consuming online pornography increase an individual’s likelihood of cheating on their spouse by nearly 70 percentage points.2

Advances in technology continue to increase opportunities for infidelity related behaviors, and as a result, our very understanding of fidelity is being altered. Social networking has particularly become a catalyst for infidelity, as online sites often act as “vehicle[s] for communicating with alternative partners.”3

While there are differing opinions4 as to what constitutes infidelity, most would agree that fidelity in relationships is worth protecting. Not only can the lack of fidelity increase the risk of divorce, it can also result in decreased relationship satisfaction,5 and is “reliably associated with poorer mental health, particularly depression/anxiety and PTSD.”6 Additionally, according to a 2017 study of married parents, engaging in unfaithful behaviors on social networking sites is “significantly related to... greater ambivalence as well as greater attachment avoidance and anxiety in both men and women.”7

Fueled by an understanding of these potential costs of infidelity, researchers have sought to better understand protective factors, and in recent years, have consistently found that religion can be a powerful defensive tool.8 Based on these studies, we know that religious worship service attendance,9 the perception of the marriage as sacred or blessed,10 and a sense of shared values by one’s congregation11 can all contribute to the fortification of the marriage relationship by lowering risks of infidelity.

A further analysis of the iFidelity survey sheds additional light on these previous findings by demonstrating that personal religious importance also plays a significant role in protecting couples from infidelity. As seen in the chart below, those with no religious affiliation and low personal religious importance were about 30 percentage points more likely to be unfaithful to a spouse than either Conservative or Mainline Protestant individuals with high personal religious importance. Even among those affiliated with a religion, those with low personal religious importance were 15 to 16 percentage points more likely to be unfaithful to a spouse than those who reported high personal religious importance.12

Why is personal religious importance such a significant deterrent in the face of infidelity? Perhaps part of the answer lies with the view of marriage as a sacred union. Religious individuals may view marriage as not only signifying commitment to one’s spouse, but also commitment with the divine or with a higher power.13 An individual with a high level of personal religious importance may therefore prioritize those commitments over other competing values in order to defend such a bond.

As New York Times columnist David Brooks has explained, in a society that prioritizes individuality above all else, “Marriage . . . which relies on a culture of fidelity, is now asked to survive in a culture of contingency” and “is now more likely to be seen as an easily canceled contract.”14 When marriage is viewed in this way, infidelity-related behaviors, such as forming an emotional relationship with an online user, may be viewed as less serious than when the relationship is viewed as a sacred union with commitments both between the individuals and a higher power. When religion is seen as a central part of life, relationships may come with an added “sense of accountability to obey . . . commandments regarding issues relating to marriage;”15 thus adding to the relationship’s fortification.

Amidst the changing definitions of sexual loyalty and commitment, valued religious beliefs and morals may also serve as a foundation for couples to stand on. Regular church attendance and religious study may result in frequent refreshers on the importance of values that can protect a marriage relationship, such as temperance and honesty. According to Chris Esselmont and Alex Bierman in a 2014 study, “when religion is highly salient to individual identify, religious beliefs shape the meanings attached to various behaviors and enhances the value placed upon these behaviors.”16 Thus, a foundation of faith may provide spouses with additional tools to decipher or recognize the meaning of and potential danger in various behaviors, both online and in real life, which could weaken their marriage relationship.

These research findings provide additional evidence of the significant contribution religion can make to fortify fidelity in marriage. An impenetrable fortress requires a culmination of protective factors. When granted high importance in our lives, faith can serve as a type of watch tower, warning us of the threats that wait beyond the walls of our family. Faith can remind us of the sacredness and value of what we are defending. Faith can unite loved ones together through shared values and beliefs, helping them work together to protect the relationship they have built. Perhaps with a clearer understanding of how faith can fortify a marriage, we can be better prepared to defend it against both the off line and online attacks it faces in the modern world.

Mariah Sanders is a senior undergraduate student in the Human Development program at Brigham Young University’s School of Family Life and worked as a summer intern with the iFidelity project. Julie H. Haupt is an Associate Professor in the School of Family Life at Brigham Young University and actively mentors students to share contemporary and crucial research findings on the family. Dr. Jeffrey Dew is an associate professor in the School of Family Life at BYU, a fellow at the National Marriage Project, and a visiting fellow at the Wheatley Institution.

1. Brody, J., "When a partner cheats," The New York Times, 1/22/18.

2. Wilcox, W. B., Dew, J. P., & VanDenBergeh, B. State of our Unions 2019. iFidelity: Interactive technology and relationship faithfulness. (Charlottesville, VA: National Marriage Project, 2019).

3. McDaniel, B. T., Drouin, M., & Cravens, J. D. (2017). Do you have anything to hide? Infidelity-related behaviors on social media sites and marital satisfaction. Computers in Human Behavior, 66, 2.

4. Guitar, A. E., Geher, G., Kruger, D. J., Garcia, J. R., Fisher, M. L., & Fitzgerald, C. J. (2017). Defining and distinguishing sexual and emotional infidelity. Current Psychology: A Journal for Diverse Perspectives on Diverse Psychological Issues, 36(3), 434-446; Wilson, K., Mattingly, B. A., Clark, E. M., Weidler, D. J., & Bequette, A. W., "The gray area: Exploring attitudes toward infidelity and the development of the Perceptions of Dating Infidelity Scale," The Journal of Social Psychology, 151, no. 1 (2011): 63-86.

5. McDaniel, B. T., Drouin, M., & Cravens, J. D. "Do you have anything to hide? Infidelity-related behaviors on social media sites and marital satisfaction," Computers in Human Behavior, 66 (2017): 88-95.

6. Fincham, F. D., & May, R. W., "Infidelity in romantic relationships," Current Opinion in Psychology, 13, no. 70 (2017).

7. McDaniel, Drouin, & Cravens (2017).

8. Dollahite, D. C., & Lambert, N. M., "Forsaking all others: How religious involvement promotes marital fidelity in Christian, Jewish, and Muslim couples," Review of Religious Research, 48 no. 3 (2007): 290-307; Esselmont, C., & Bierman, A., "Marital formation and infidelity: An examination of the multiple roles of religious factors," Sociology of Religion, 75, no. 3 (2014): 463-487.; Jeanfreau, M. M., & Mong, M., "Barriers to marital infidelity," Marriage & Family Review, 55, no. 1 (2019): 23-37.

9. Fincham, F. D., & May, R. W., "Infidelity in romantic relationships," Current Opinion in Psychology, 13 (2017): 70-74.; Jeanfreau & Mong (2019).

10. Esselmont, C., & Bierman, A., "Marital formation and infidelity: An examination of the multiple roles of religious factors," Sociology of Religion, 75, no. 3 (2014): 463-487.

11. Esselmont, C., & Bierman, A. "Marital formation and infidelity: An examination of the multiple roles of religious factors," Sociology of Religion, 75, no. 3 (2014): 463-487.

12. Wilcox, W. B., Dew, J. P., & VanDenBergeh, B., State of our Unions 2019. iFidelity: Interactive technology and relationship faithfulness. (Charlottesville, VA: National Marriage Project, 2019).

13. Dollahite, Lambert, (2007); Jeanfreau & Mong (2019).

14. Brooks, D. "The power of marriage," The New York Times, 11/22/03.

15. Dollahite & Lambert (2007).

16. Esselmont, C., & Bierman, A. "Marital formation and infidelity: An examination of the multiple roles of religious factors," Sociology of Religion, 75, no. 3 (2014): 468.