Highlights

- Our analysis of a new AEI survey indicates that marriage acts as a buffer against loneliness for Americans stuck at home, shielding many men and women from feelings of isolation. Post This

- Young children do not appear to buffer against loneliness in the time of coronavirus. In fact, parents are more likely to report feelings of loneliness than non-parents and those with adult children. Post This

- It looks like parenting amidst the pandemic is more bearable for those with a married partner at home. Post This

The stay-at-home orders issued in connection with the coronavirus pandemic are exacting unprecedented costs not only on the United States economy but also on the emotional and social welfare of millions of Americans. Because human beings are social animals, prolonged social distancing is taking a toll on millions of men and women across the nation.

The costs of social distancing are moderated by many factors, including employment, geography, and income. Here we focus on another critical factor: family. A recent survey fielded in late March 2020 by our colleagues at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI) offers unique insights into how marriage and parenthood are associated with feelings of loneliness and isolation amidst the pandemic. The “American Perspectives Survey,” conducted from March 26-30, 2020, asked 2,560 adults questions how frequently they have felt lonely or isolated amidst social distancing practices, as well as questions about their relationship and parental status.

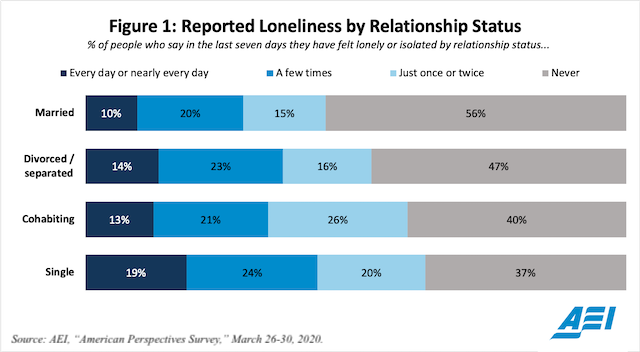

Our analysis of the survey indicates that marriage acts as a buffer against loneliness for Americans stuck at home, shielding many men and women from feelings of isolation. Whereas 43% of single people and 37% of divorced or separated people reported they felt lonely or isolated a few times or more in the previous seven days, only 30% of married people gave the same answer (figure 1). Even those who were in a cohabitating relationship were more likely to report feeling lonely or isolated at least once than married men and women. Because it supplies people with not only another adult to with whom to ride out the pandemic but also higher levels of commitment, marriage may engender a heightened sense of connection for men and women in this difficult time.

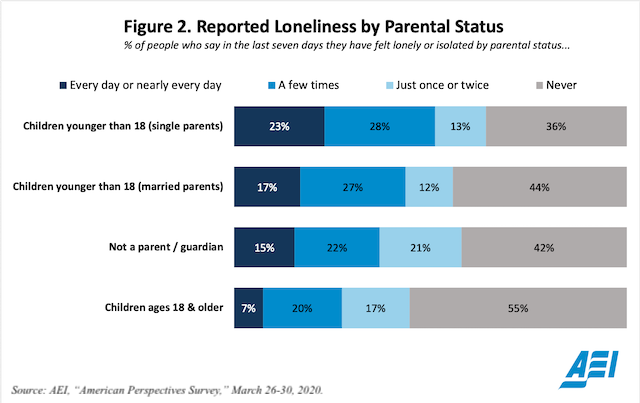

But young children do not appear to buffer against loneliness in the time of coronavirus. In fact, as shown in figure 2, parents are more likely to report feelings of loneliness than non-parents and those with adult children. Among different parental groups, the survey indicates that those least likely to report loneliness were those with at least one child aged 18 or older. Of these respondents, only 27% said they felt lonely or isolated at least a few times in the past seven days. Meanwhile, parents with children under the age of 18 were more likely to struggle with feelings of isolation than those who did not have any children at all. Though here again, single parents were more likely to report loneliness than others in this group.

Note: “Single parents” in the above figure were defined as respondents who identified their

relationship status as “single,” “divorced,” “separated,” or “in a relationship but not living together.”

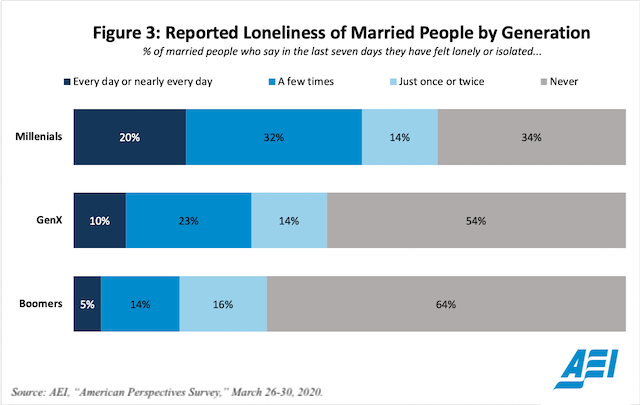

Finally, this loneliness divide also varies across different generations. When we accounted for marital status across age groups, we found that older generations consistently reported lower levels of loneliness when compared to their younger peers. For example, only 5% of married Boomers said they felt lonely or isolated every day or nearly every day, compared to 20% of married Millennials who said the same (figure 3).

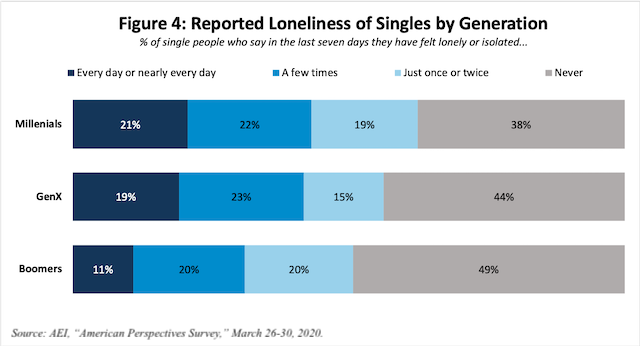

There was also a generational divide in loneliness for single adults, with Boomers reporting loneliness at much lower rates when compared with Millennials, as figure 4 indicates.

One surprising pattern we noticed when comparing figures 3 and 4 was that Millennials appear to be standouts among other generations in how deeply their social lives have been hit by this crisis. For GenXers and Boomers, marriage seems to be effectively insulating people from feeling lonely. However, among Millennials, marriage does not appear to have this same effect. In fact, married Millennials were even more likely than their single peers to report feelings of loneliness. This generational story deserves further study.

In general, however, this research brief suggests that family cuts in two different ways for Americans now living under pandemic-related stay-at-home orders. Marriage seems to buffer men and women against feelings of loneliness, whereas parenting young children increases the odds that they struggle with feelings of loneliness or isolation. In other words, it looks like parenting amidst the pandemic is more bearable for those with a married partner at home.

W. Bradford Wilcox is professor of sociology at the University of Virginia and a visiting scholar at the American Enterprise Institute. Peyton W. Roth is a research assistant in poverty studies at the American Enterprise Institute.