Highlights

- In a new paper published in Social Science Research, we find that premarital sex indeed reduces the chances of marriage, but only in the short term. Post This

- There’s a strong correlation between premarital sex partners and marriage rates. Post This

- Some adults have seasons of sexual activity, periods of behavior that have no bearing on whether they’ll eventually get married. Post This

Would you “buy the cow if you got the milk for free”?

That offensive bit of folk wisdom, based on the premise that heterosexual women trade sex for commitment, is the thesis of sociologist Mark Regnerus’ controversial 2017 book, Cheap Sex. Dr. Regnerus, who teaches at the University of Texas, proposed free milk-commitment-free sex as a major cause of the well documented decline in marriage rates over the past half century. Yet he never actually tested his hypothesis with national data.

This is a strange omission. The free milk-and-cows aphorism has been around for centuries. Previous studies have explored just about every other aspect of the relationship between premarital sex and marriage. Writing for the Institute for Family Studies, Wolfinger has shown that premarital sex partners reduce marital happiness and increase the odds of divorce (albeit not uniformly), but to date, no one has used national data to ascertain whether multiple sex partners really do make getting married less likely.

In a paper just published in Social Science Research, we provide a more definitive answer to this question. And it’s fairly straightforward: premarital sex indeed reduces the chances of marriage, but only in the short term. In the long term, your full sexual history doesn’t matter.

To be sure, the purported abundance of free milk was always based more on aspiration than reality. Nowadays the median American man has five premarital partners, while the median woman has three. Promiscuity is fairly rare, especially for women: 5% of women have had 16 or more partners; 5% of men have had 50 or more. In Regnerus’ telling, casual sex is bolstered by masturbation and pornography, another form of commitment-free sexual activity. Yet Perry has shown that porn use makes men more desirous of marriage (this same paper also finds that men who report frequent hookups and onanism are no less desirous of marriage).

To test the free milk hypothesis, we analyzed two national data sets. The National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) offered a large sample and the information necessary for causal modeling, but it is cross-sectional and limited to female respondents. The 1997 cohort of the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY) offers panel data on both men and women that allow us to test hypotheses about the timing of sex partners and marriage rates.

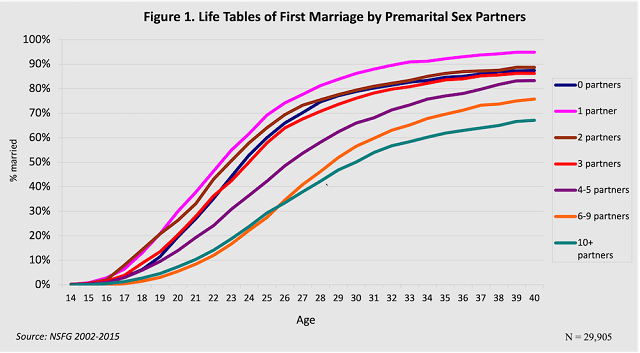

The NSFG establish that there’s a strong correlation between premarital sex partners and marriage rates. Women are most likely to get married if they have exactly one premarital sex partner, no more and no less. Ninety-five percent of such women have tied the knot by age 40. The corresponding number for virgins is eight percentage points lower, at 87 percent. And past one partner, there’s a steady decline in marriage rates. This ranges from 89% for women with two premarital sex partners, all the way down to 67% for women who report 10 or more partners. That’s a big difference.

Does correlation equal causality in this case? To address this question, we estimated bivariate probit models that account for unobserved differences between respondents.1 The answer is straightforward: premarital sex partners have a causal effect on marriage.

Since the data are retrospective, the NSFG tells us nothing about whether the timing of sex partners matters. This is a sensible possibility: shouldn’t early sexual activity, perhaps in college, have less bearing on marriage rates than more recent multi-partner frivolity?

To address this question, we turn to 15 waves of panel data2 from the NLSY. These respondents were first interviewed in 1997, when they ranged from 14-22 years old. Thereafter they were re-interviewed annually or biennially, meaning they were in their 30s and 40s by the end of our study. This left us with data for all the years in which first marriage and casual sex—sex that might not lead to a lasting union—are most common.

We used two different measures of sexual activity for the NLSY: sex partners in the year of each interview, and lifetime sex partners. On their own, each is negatively correlated with marriage. But here’s the catch: put them both in a regression model, and only recent partners matter. In other words, it matters what you’re doing, not what you’ve done. Moreover, this finding holds for both men and women, and persists even after a laundry list of statistical controls: age, race/ethnicity, region of the country, urban vs. suburban vs. rural residence, family structure of origins, parental education, premarital childbirth, cohabitation, respondent education, and religion.

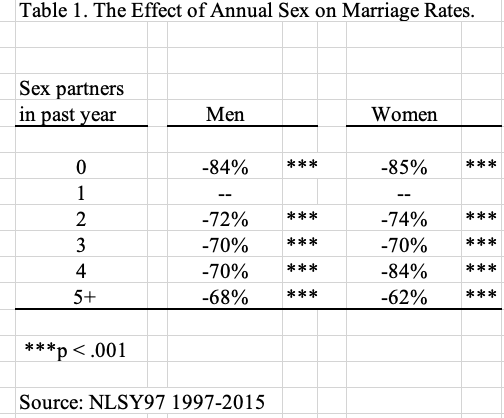

How large are the effects of annual partners? Table 1, below, has the answers. Having anything other than one partner in a given year leads to much lower odds of marriage. The lowest marriage probabilities are for respondents with no partners, and the effects for men and women are virtually identical: compared to their peers with just one sex partner, adults who have not had sex in the previous year are 84-85% less likely to tie the knot. These figures are even larger than are the reduced chances of marriage for anyone having two or more sex partners in a given year. Compared to a single partner, having two or more sex partners reduces the probability of marriage by anywhere from 62% to 84%, with no clear trend or gender difference in these results.

The upshot of these results is that some adults have seasons of sexual activity, periods of behavior that have no bearing on whether they’ll eventually get married. This result casts doubt on the Regnerus notion that cheap sex is responsible for the declining marriage rate, at least in the main. It’s possible it holds true at the margins—that some people are eschewing marriage for easy access to sex—but it’s not the main story.

Our results are equally clear about the short-term consequences of cheap sex: it makes marriage far less likely. It’s normal for people to become monogamous when a relationship becomes serious and when marriage becomes a possibility.

The upshot: Contrary to the common aphorism, marriage is a possibility for people irrespective of their earlier relationship to free milk.

Nicholas H. Wolfinger is Professor of Family and Consumer Studies and Adjunct Professor of Sociology at the University of Utah. He is the author of Thanks for Nothing: The Economics of Single Motherhood since 1980, coauthored with Matthew McKeever, forthcoming from Oxford University Press. Samuel L. Perry is an associate professor of sociology at the University of Oklahoma. He has written widely on the intersections of religion, sexuality, and family life. His two books in this area include Growing God's Family (NYU 2017) and Addicted to Lust (Oxford 2019).

Editor's Note: The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or views of the Institute for Family Studies.

1. These models are identified using age at menarche, a predictor of sexual behavior that has no logical relationship to marriage rates. Please consult our paper for further details.

2. The analysis is limited to heterosexual marriages due to data limitations.

Appendix