Highlights

Go ahead. Admit that you occasionally look at the magazines at the check-out counter of your local supermarket. Given all the how-to tips for the bedroom and breathless accounts of celebrity hookups on the magazine covers, you might be forgiven for not knowing that Americans have become less sexually promiscuous in recent years. Is this equally true for both men and women, and does it matter whether you’re a college graduate? The answers to these questions may speak to the social class divide in marriage.

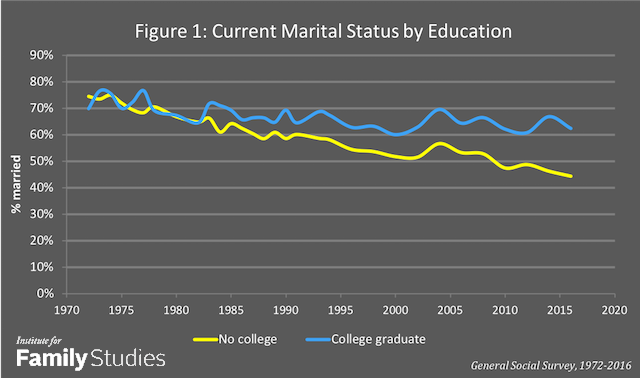

This divide, gradually emerging over the past few decades, has become a commonly acknowledged feature of American inequality. Almost 50 years of data from the General Social Survey show that over 70% of survey respondents were married in the 1970s. Back then Americans with and without four-year college degrees were equally likely to be married. In the following decades marriage rates plummeted for people who hadn’t finished college but only declined modestly for their college graduate peers. By 2016 the marriage gap was about as large as it’s ever been: 62% of Americans with four-year college degrees were married, compared to 44% of those without degrees. The gap is even larger for younger Americans.

Note: N = 62,292. Results are weighted.

The retreat from marriage has both cultural and economic roots, as W. Bradford Wilcox and I contend in our book Soul Mates: Religion, Sex, Love, and Marriage among African Americans and Latinos. Some of the cultural roots stem from the introduction of modern contraception in the 1960s and the concomitant liberalization of sexual mores. As economists George Akerlof and Janet Yellen have observed, contraception undermined men’s obligation to marry the women they had impregnated; a woman’s fertility became her responsibility. At the same time, ambassadors for female sexuality like Helen Gurley Brown called for women to enjoy sex on its own merits, whether or not they were married. The late James Q. Wilson posited that these cultural trends were more likely to be consequential for less prosperous Americans, often those without four-year college degrees.

Questions remain about how declining marriage rates and the rise of nonmarital sexuality might be related. Conservative sociologist Mark Regnerus contends that the ready availability of sex—in his words, “cheap sex”—destroys much of the incentive men have for marriage. If that’s the case, we would expect to see a surge in male sexual activity in recent years that’s focused on men without college degrees; that is, the men now less likely to tie the knot. The secular decline in marriage should be mirrored by a steady increase in sex, and men who didn’t graduate from college should be having more sex than in the past.

But that doesn’t seem to be the case. Using data from the 1989-2014 General Social Survey, psychologist Jean Twenge and her colleagues have found that unmarried adults’ sexual frequency hasn’t changed much over time. What has changed, according to Twenge, is who they’re having it with: Millennials have had fewer sex partners on average than the generations of Americans born in earlier years.

Assuming a relationship between the foregoing trends in sex and marriage, the decline in sexual partners shouldn’t be evenly distributed across education groups. Instead, numbers of sex partners should have declined more for younger Americans with college degrees, based on the fact that most college graduates will get married and stay married (and a large and growing majority of marriages are monogamous).

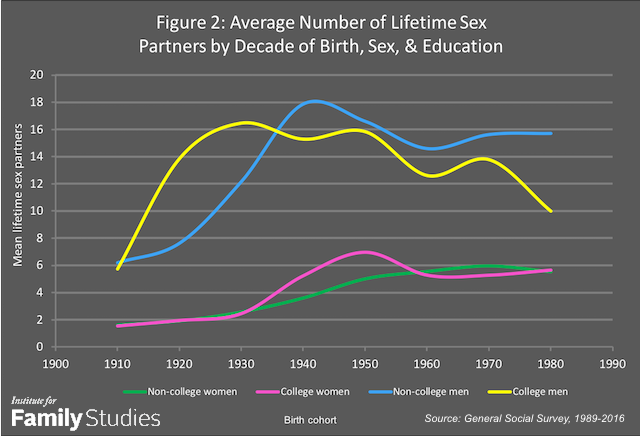

This supposition about declining sex partners is only partially borne out by the facts. I organized 27 years of data from the 1989-2016 GSS by decade of birth—earlier surveys don’t ask about sexual biographies—then plotted the average number of lifetime sex partners by respondent sex, education, and decade of birth. The tally of sex partners ignores sexual orientation. Respondents younger than 24 years old were excluded from the analysis in order to ensure adequate time for college completion. Finally, too few GSS respondents were born in the 1990s to include them in the data analysis.

Note: N = 28,317, GSS 1989-2016. Results are weighted.

Overall, the trend for Americans born since 1910 is towards more sex partners over time. Figure 1 shows that men have always had more sex partners than women. Education has made little difference in women’s sexual behavior, except for women born in the 1940s and 1950s. Presumably, attending college at the height of the sexual revolution increased women’s sexual adventurousness. Men born before 1940 had more sex partners if they had college degrees. The reasons for this are difficult to discern from my analysis of retrospective data in 2018.

The most interesting development concerns the declining number of sex partners for college-educated men born after the 1960s. They have had almost four fewer partners than their peers without four-year college degrees, a difference that is statistically significant. Over the same years, average sex partners held steady for the other population groups under consideration here.

Although Twenge and other scholars have looked at mean trends in sexual partners, this approach has a disadvantage. Arithmetic means are artificially inflated by outliers, those unusually adventurous folks who’ve had 50, 100, or more partners. Ninety percent of women have had 10 or fewer partners; 90% of men have had 30 or fewer. But the data go as high as 367 for women and 750 for men (the latter value seems to imply a Lothario prone to rounding). These high values mean that averages will be artificially inflated, and therefore fail to capture typical patterns of American sexuality.

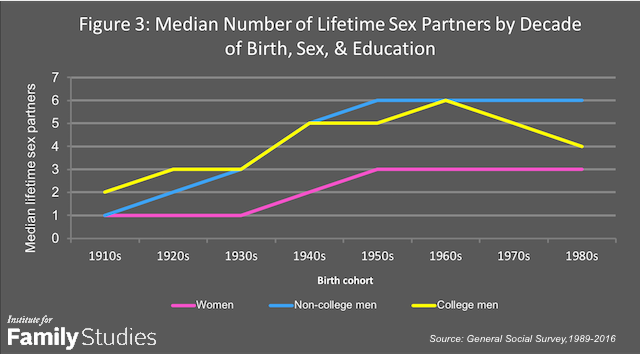

Note: N = 28,317, GSS 1989-2016. Results are weighted.

Predictably, medians suggest much more modest American sexual biographies. College hasn’t had any effect on women’s partner counts. The median woman born after the 1940s has had three sex partners in her lifetime. Men have always been more promiscuous, with medians as high as six. This number hasn’t changed for men born after the 1940s who don’t have four-year college degrees. However, college-educated men born after the 1960s have steadily fewer partners. The median for those born in the 1980s is four; for men born in the same years who didn’t finish college, the corresponding number is six. Thus, medians show the same decline in sex partners for college-educated men as do averages.

Multivariate analysis of the education-partner gap for men born since the 1960s did not reveal a statistical smoking gun, a single responsible cause. One thing that does appear to play a part is a person's family structure of origin. Social science has long known that the offspring of two-parent families have fewer sex partners and are more likely to attend college. This is the case for the data analyzed here, and controlling for family structure partially accounts for the partner gap between college-educated and non-college-educated men. But it’s far from being the only thing that matters.

People are waiting longer than ever to get married for a variety of reasons. The median American groom is almost 30; the median bride is about 28. Modern sexual mores, abetted by contraception and now attended to by a multitude of dating websites and apps, mean that young adults don’t have to marry quickly to avoid languishing in celibacy. But this all seems to matter less now for college-educated men, who now typically report having fewer lifetime sex partners than men born between the 1940s and the 1970s. Perhaps they’re pursuing demanding careers that preclude adventurous sexuality (or any sexuality at all, in some cases) prior to marriage. It’s also possible that new digital entertainments, from video games to porn, are proving more compelling than dating. None of this holds true for college-educated women, whose sexual adventurism hasn’t changed much for decades. Although women spend almost as much time as men playing video games, they only watch one third as much porn.

The flipside is men without four-year college degrees, who are marrying at historically low rates. In recent decades they’re less likely to have demanding careers, instead subsisting on a thin gruel of low paying service-sector employment. This is one of the reasons they’re marrying later and marrying less, although it’s not the only one. In lieu of marriage, these men apparently lack the incentive to cut down on their traditional male tomcatting.

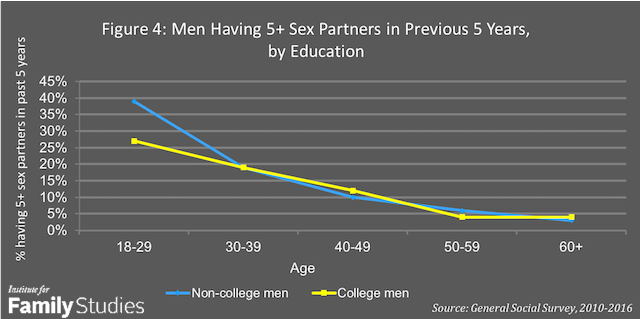

My estimates of promiscuity for recent birth cohorts are biased downward. These respondents are mostly on the young side: anyone born in the 1980s, for instance, is under 40 years old. Do decades of promiscuity lie in the future for these men? Probably not, according to the GSS data. The chances of having multiple partners go down considerably as men get older. This is demonstrated by Figure 4, which breaks down the percentage of men who’ve had five or more sex partners in the past five years.

Note: N = 3,061. Results are weighted.

Taken together, what do these results say about the relationship between promiscuity and marriage? Not much. Adults born in the 1980s have had had about as many sex partners as those born in the 1950s, but much lower marriage rates. Women remain about as (un)promiscuous as they have for decades, whether or not they have four-year college degrees. The exception has been college-educated men. Their marriage rates have fallen, albeit more slowly than their less educated peers, over the same years they became markedly less promiscuous.

It’s clear that the sexual revolution of the 1960s and 1970s permanently changed American sexual behavior. It’s easy to believe that the modern acceptability of premarital sex removed one strong rationale for youthful marriage. Nevertheless, the data presented here don’t really support the view that a substantial number of men are eschewing marriage thanks to easy access to sex. Promiscuity hit its modern peak for men born in the 1950s and never rose, but marriage rates continued to fall. If men came to eschew marriage for cheap sex, men should have had more sex partners over time. But they haven’t. The numbers just aren’t there.

Nicholas H. Wolfinger is Professor of Family and Consumer Studies and Adjunct Professor of Sociology at the University of Utah. His most recent book is Soul Mates: Religion, Sex, Love, and Marriage among African Americans and Latinos, coauthored with W. Bradford Wilcox (Oxford University Press, 2016). Follow him on Twitter at @NickWolfinger.

Editor’s Note: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or views of the Institute for Family Studies.