Highlights

America’s kids are unhappy: 3.5 million teenagers experienced major depression in 2018, continuing a surge since 2012. Rates of teen suicide have increased steadily since 2007. And new data indicate that rates of depression and anxiety are also up among college students, suggesting that unhappy teens do not cheer up when they leave home.

These disturbing trends have prompted a robust debate about underlying causes and, in particular, the role that smartphones, screens, and social media all play. Has our national experiment with widespread tech use made our kids miserable?

Although heated, the current debate suffers in many ways from a paucity of data. Just a handful of big data sets—predominantly the Monitoring the Future and Youth Risk Behavioral Surveillance surveys—contain any indicators at all about teens’ screen use. These do more than their share of work as objects of dispute. There have been a number of longitudinal studies, but these follow only a few measures. Neuroimaging research, although promising, is still in its infancy.

The real problem is, as psychologist Jean Twenge and others have compellingly argued, that the American experience of being a teen has been radically transformed, and we have very little insight into how teens are experiencing that change. Today’s teens are what linguist Gretchen McCulloch recently labeled, “post-internet people,” or kids who have grown up fully immersed in the new digital culture. Whether or not screens caused the depression spike is just the tip of the iceberg; more research is desperately needed into how tech is changing every aspect of teen life.

Enter the fine folks at the Pew Research Center, who last year released a survey of 743 teens (ages 13 to 17) and their 1,058 parents, asking about their experience of adolescent screen use. The raw data are not yet available, Pew told me, but the original two reports and a second analysis released in late August provide invaluable insight into how today’s teens actually feel about screens.

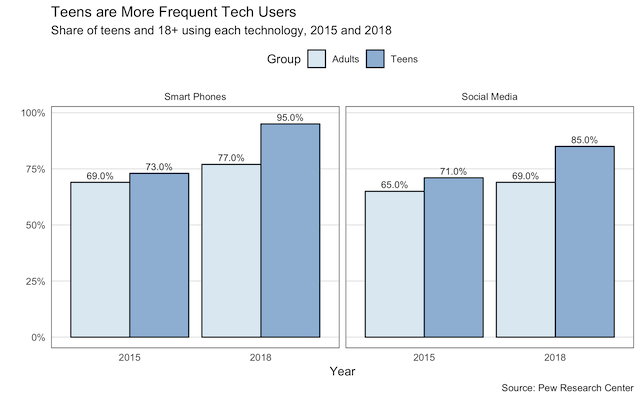

First, some raw numbers. Pew has helpfully tracked smartphone ownership among the general population since 2011. Then, 35% of U.S. adults owned smartphones; as of 2018, 77% did. Teens, however, are more aggressive adopters. In 2015, 73% of teens owned a smartphone compared to 69% of adults; in 2018, 95% of teens had a smartphone, 18 percentage points more than adults.

The gap is similar for social media.1 In 2015, 65% of adults used social media compared to at least 71% of teens; in 2018, the gap widened to 69% versus at least 85 percent.

Within the 13-to-17 age group, smartphones are pervasive. For example, teens whose parents make in excess of $75,000 a year are 1.3 times more likely to own a desktop or laptop computer than those whose parents make less than $30,000, but only 1.04 times as likely to own a smartphone. The same disparity persists when looking at standard educational or racial inequities—as of 2015, in fact, Pew found that “African-American teens are the most likely of any group of teens to have a smartphone.” Social media usage is similarly constant across racial, educational, and economic lines.

Smartphones and social media, then, are basically ubiquitous among teens, regardless of socioeconomic status. How do they actually feel about that? The answer, the Pew data suggest, is “mixed.”

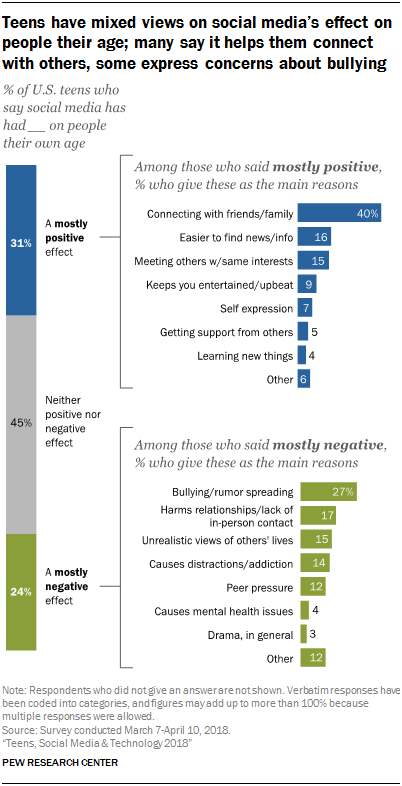

When asked how social media has impacted people their age, 31% of teens said it had a “mostly positive” effect, 24% a “mostly negative” effect, and 45% “neither positive nor negative effect.” In other words, while many researchers are certain that screens definitely are a negative, or positive, force in teens’ lives, adolescents themselves are far more equivocal.

Where teens say social media is positive, it is largely because of the connections it fosters. Those who responded “mostly positive” cited not only connecting with family and friends but also “meeting others with the same interests.” The same is true of smartphones: 83% say they use their phones for “connecting with other people.”

“I feel that social media can make people my age feel less lonely or alone,” one 15-year-old girl told Pew. “It creates a space where you can interact with people.”

While that connection seems like a benefit, Pew’s data also reveal many costs. For many teens, screens might be habit-forming: 45% say they are online “almost constantly;” 54% say they spend too much time on their phones, and 41% say they spend too much time on social media. Additionally, 72% often or sometimes check their phones immediately upon waking up, and more than half have taken steps to limit their own phone and social media use.

That compulsive behavior flows naturally into self-reported negative psychological experiences. For example, 56% say they are lonely, upset, or anxious if they don’t have their phone; only 17% say that they are relieved or happy. But that may not be because screens directly cause mental health issues—only 4% of those who thought social media were mostly negative suggested such a cause—but because of social experiences it facilitates. Among those who disliked social media, the modal respondent said it was “mostly negative” because it facilitated “bullying/rumor spreading.” Others thought it harmed relationships, or lead to a lack of in-person contact.

Teens’ overall ambivalence about screens occludes an important underlying divergence. Specifically, the negative effects of screens seem to more strongly affect girls than boys. Roughly half of girls are near-constantly online, anxious without their phones, say they spend too much time on social media, and use their phones to avoid other people. In each of these categories, they outpace their male peers by 11, 14, 12, and 13 percentage points, respectively.

To the extent that screens affect mental well-being, then, it is likely that the effect concentrates among girls. Teen girls experience more anxiety, depression, and loneliness, and attempt suicide more frequently than their male counterparts (although the latter complete suicides more frequently). It isn’t clear why, although one possibility is that social media is more conducive to negative manifestations of female social interaction than male social interaction.

Beyond that distinction, the picture these data paint is more complicated than screens simply making teens happy or depressed. Rather, what they seem to be experiencing is a normal adolescent experience—a desire for connection, anxiety about rejection, a fear of bullying—refracted through the novel medium of smartphones and social media. These platforms, which facilitate more connections than have been historically available to humans, might “supercharge” both the positives and negatives of adolescence, rather than just one or the other.

The other important takeaway is that systematically talking to teens matters. The underlying causes of the spike in teen depression remain largely a mystery, but their effects—including more than 2,000 suicides a year—are obvious. Robust studies and neuroimaging matter to understanding the long-run effect of screen culture. But just as important, and much easier, is the sort of comprehensive survey work Pew is trying to do, work which tries to understand what is happening to our kids by actually asking them.

Charles Fain Lehman is a staff writer for the Washington Free Beacon, where he covers crime, law, drugs, immigration, and social issues. Reach him on twitter @CharlesFLehman.

1. Pew did not report total rates of social media use across all sites for teens; rather, the “at least” figures represent the share that uses the most popular social media site in each year. The true proportion is therefore almost certainly higher.