Highlights

- Jean Twenge corrects several inaccuracies in a recent NPR article on teens, screens, and mental health. Post This

- When presented accurately, it’s very clear that adolescents are suffering from more mental health issues than they were 10 years ago, and these increases began in the age of the smartphone and ubiquitous social media. Post This

- If we’re not going to worry about technology use, then we might as well also write off heroin use, exercise, and obesity when it comes to teen mental health. Post This

In the years around 2010, something started to go wrong in the lives of American teens—the group I call iGen. Adolescent depression spiked, loneliness increased, and life satisfaction fell. It’s difficult to say definitively why this occurred, but technology use might have something to do with it. The first iPhone was introduced in 2007, and by 2013 the majority of Americans owned a smartphone. During this same time, social media moved from optional to virtually mandatory among teens. At the same time, face-to-face interaction among teens declined, and the number who weren’t sleeping enough increased.

National Public Radio (NPR) recently published a piece on this topic by Anya Kamenetz, who has her own book on kids and technology. I talked to Kamenetz for more than an hour and referenced a raft of papers on the trends in adolescent mental health. When her piece was released by NPR earlier this week, however, I was disappointed to see that it was filled with inaccuracies. When I e-mailed Kamenetz, I got a message saying she was away on vacation until September 3. I’d rather not let these inaccuracies stay uncorrected for that long, so I will lay them out here with five points.

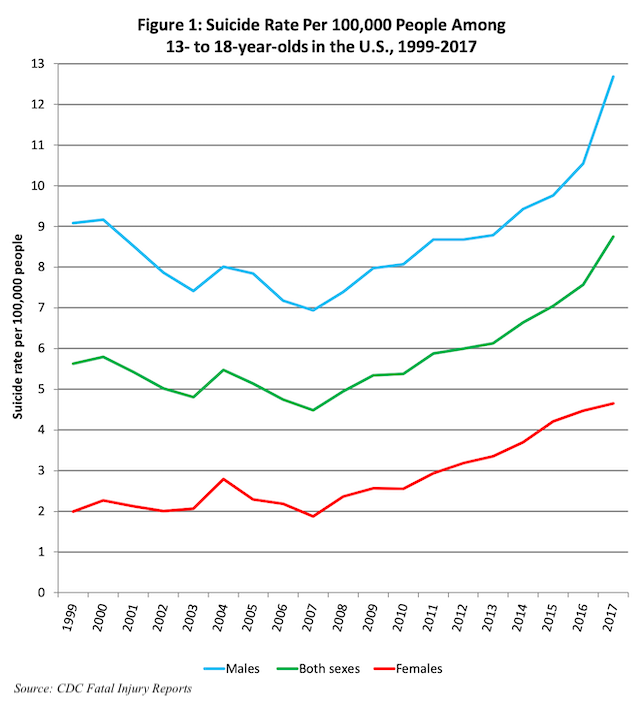

1. Kamenetz writes that “there are lots of numbers that don't necessarily fit Twenge's theory” (about teen mental health issues increasing around the same time smartphones and social media became popular). She mentions two trends as evidence. First, she says, “The uptick in suicides started in 1999.” Not true. Here is the CDC data on suicides among 13- to 18-year-olds in the U.S. from 1999 to 2017:

This figure clearly shows some decline or no consistent change between 1999 and 2007, and then a consistent rise beginning in about 2008. How, then, could Kamenetz write that suicide began to rise in 1999? My best guess: She confused the starting year of the data (1999) with the year the increase began (2008). It’s also possible that she’s referring to the increase in suicide among adults, but since the rest of the article is about adolescents, I can’t see why that would be the case.

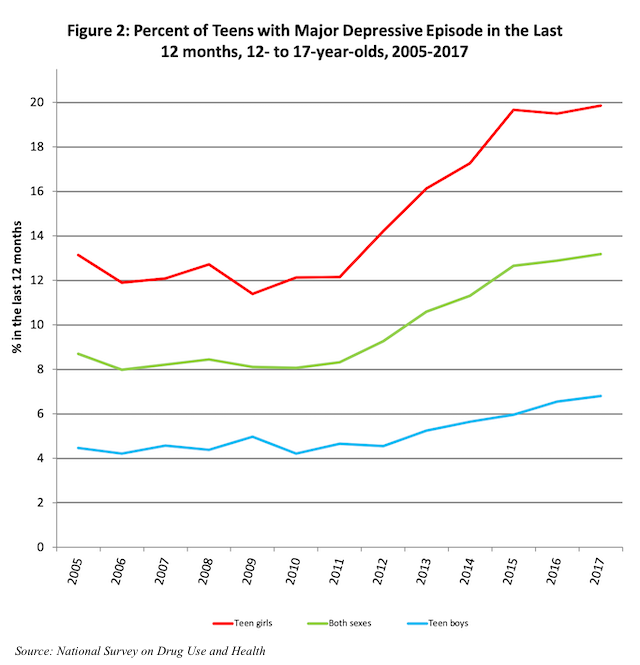

2. Second, Kamenetz writes that “The downturn in teen mental health started in 2005.” This is also not accurate. Here is the data on clinical-level depression from a national screening study:

This clearly shows little change between 2005 and 2011, and then increases starting with 2012, especially among girls. Again, I suspect she confused the starting year of the data (2005) with when the increase began (2012).

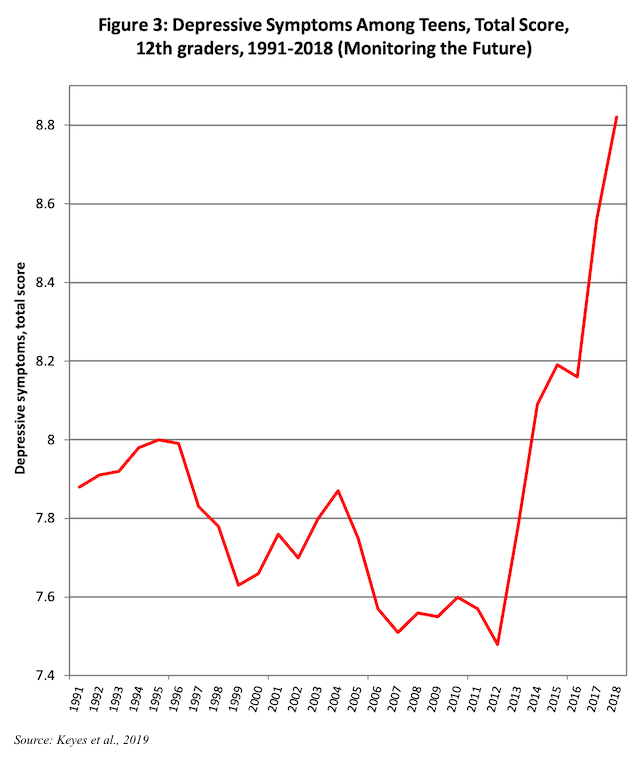

3. Next, Kamenetz interviewed Katherine Keyes, an epidemiologist at Columbia University who has studied trends in adolescent mental health, and summed up the trends this way: “Adolescent mental health isn't in ‘free-fall,’ says Keyes, but seems to have leveled off since a dip in 2012.”

But that is not what Keyes’ own research shows. Here’s a direct quote from Keyes’ recent paper on trends in mental health among adolescents: “Symptoms of depression are increasing among US students aged 13–18 years through 2018, with the largest increases occurring among girls since 2012.”

Thus, the statement that adolescent mental health has "leveled off" since 2012 is completely false, based on Keyes’ own paper. Here is the trend for all 12th graders, which I graphed using the means from Keyes’ Supplementary Table 1:

The increase in depressive symptoms after 2012 could not be more clear; there is no “leveling off.”

4. Furthermore, Kamenetz interviewed Amy Orben, a graduate student at Oxford, who offered an alternative explanation for the trends in adolescent mental health: “And, [Orben] adds, there's a chance that young people today may simply be more open in surveys when asked about mental health challenges. ‘A lot of teenagers are a lot more OK to say they're not OK.’” Importantly, Kamenetz does not include the evidence that completely refutes this argument: Hospital admissions for self-harm, self-poisoning, and suicide attempts have also increased since 2010, and these trends in behaviors can’t be explained away by self-report tendencies on surveys—and neither can the increase in completed suicides. These studies have received extensive press coverage, and I mention the point about behaviors vs. self-report in my book ( iGen ) and in all of my journal articles on the topic. We likely discussed this during the interview as well.

5. Then, there’s this: “‘A teenagers' technology use can only explain less than 1% of variation in well-being,’ Orben says. ‘It's so small that it's surpassed by whether a teenager wears glasses to school, or rides a bicycle, or eats potatoes.”

More children and teens are being seriously hurt or dying due to mental health issues.

As I told Kamenetz in our interview, these types of comparisons can be chosen arbitrarily, so they are not very useful as objective measures of importance. One can easily choose other comparisons that give a very different impression. For example, the correlation between mental health issues and electronic device use is larger than the correlation between mental health issues and heroin use, exercise, or obesity. I provided these exact comparisons to Kamenetz in our interview, yet they are nowhere to be found in her article. But this is clearly relevant: If we’re not going to worry about technology use, then we might as well also write off heroin use, exercise, and obesity when it comes to teen mental health. I doubt many people would want to do that.

The less than 1% figure is also inaccurate—it’s based on comparisons including TV, which is not the same as “technology use” or relevant to the recent increase in mental health issues. In addition, the whole concept of “percent variance explained” went out of style several decades ago, and for good reason. As David Funder and Daniel Ozer explain in their recent paper, percent variance explained is “misleading” (their word) and “allows writers to disparage certain findings inconsistent with their own theoretical predilections.” As they and methods researcher Robert Rosenthal point out, the polio vaccine explained only .0001% of the variance in whether children get polio, but unvaccinated children were more than three times more likely to get polio. In the case of technology use, twice as many heavy users of social media (vs. non-users) are depressed (in a study by UK researchers using one of the same datasets Orben used). That is not a small effect.

Just as it’s difficult to definitively explain why adolescent mental health has suffered in recent years, it’s difficult to say why there appears to be an extreme level of denial that there’s a problem. When presented accurately, it’s very clear that adolescents are suffering from more mental health issues than they were 10 years ago, and that these increases began in the age of the smartphone and ubiquitous social media. These trends include large increases in self-harm and self-poisoning, as well as death by suicide, with the result that more children and teens are being seriously hurt or dying due to mental health issues. No matter what the cause of these trends, we need to pay attention to them. Our kids are depending on us.

Jean M. Twenge, Ph.D., is a professor of psychology at San Diego State University and the author of iGen: Why Today’s Super-Connected Kids Are Growing Up Less Rebellious, More Tolerant, Less Happy – and Completely Unprepared for Adulthood