Chapter 1: Faith and Fertility in the 21st Century

Laurie F. DeRose, Georgetown University

W. Bradford Wilcox, University of Virginia

Andrés Salazar-Arango, Universidad de la Sabana

Gloria Huarcaya, Universidad de Piura

Kuo-Hsien Su, National Taiwan University

Susana Ochoa, Universidad Panamericana

Javiera Reyes Brito, Universidad de los Andes, Chile

Abstract: Gender equality is increasingly thought to be the new natalism—the force that will bring about the reemergence of sustainable fertility from below-replacement levels of childbearing. Women who anticipate taking on a disproportionate share of childrearing responsibilities are more likely to opt out of childbearing than those who anticipate involved partners. Because religion often fosters traditional gender attitudes, its pronatalist influence could diminish in a world where gender equality is emerging as the new natalism. We use four waves of World Values Survey data from low-fertility countries in the Americas, East Asia, and Europe to show that religion’s positive influence on fertility has not, in fact, waned in recent decades. We suggest that marriage plays an important role in understanding religion’s continued positive influence: those with egalitarian gender role attitudes are less likely to be married and have slightly fewer children. Religion has become a stronger positive predictor of marriage and childbearing over time in low-fertility countries. Gender ideology and faith have interacted differently across world regions over time, but we found no region where the pronatalism associated with religion was tempered by a positive association between religiosity and gender traditionalism.

The world of the 21st century is one in which almost every country on the face of the globe has seen a decline in fertility rates and where a “retreat from marriage” is almost a near-universal as well—delays in marriage, increases in cohabitation, increases in the proportion who never marry, increases in divorce, plus various combinations of these factors. Economic affluence in general, and women’s economic independence in particular, reduce the “need” for families: individuals, both with and without state support, can live as individuals.1

This reality is a threat to sustainable fertility levels, currently manifested in a relatively small youth population. Fertility is well below the replacement level of 2.1 children per woman throughout most of the Americas, Europe, and East Asia. Ultimately, however, below-replacement fertility may prove to have been an “adjustment phase” in higher-income countries between unsustainable rapid population growth and long-term replacement fertility. That is, as countries become more egalitarian and adopt work-family policies that make it easier to juggle work and family responsibilities, fertility levels may rise to replacement levels.

This is exactly what leading population scientists thought was happening when fertility first dropped below two children per woman in Europe: below-replacement fertility was thought to be a temporary phase that might recur occasionally, but never continue for any extended period.2 Half a century later, there is no longer any reason to expect replacement fertility to reemerge out of some natural homeostatic force. Despite the economic and other costs associated with a relatively small youth population, below-replacement fertility has persisted in Europe, and it has emerged in the Americas, Eastern Asia, and scattered higher-income countries in areas of the Global South.3

The question then shifts from “when can we expect replacement fertility?” to “how can we expect replacement fertility?” If the current retreat from marriage and childbearing is in fact an “adjustment phase,” how do we need to adjust in order to emerge from it?

The leading answer to this question, at least in academic circles, is greater gender equality.4 Gender equality used to be seen as a fertility suppressant because women engaged in paid work had fewer children than others, but we have reached a time when most women in Europe, the Americas, and Eastern Asia have few children. In modern societies where women typically have high demands in the public (paid work) sphere of their lives, support from partners is necessary to make bearing two children commonplace. Today, this support often comes in the form of a father involved at home with his family. If women commonly carry a “second shift” of work after they get home from paid work, they are more likely to retreat from childbearing than if they have a supportive partner on the home front.5

For this World Family Map report, we fully embrace the notions that sustainable fertility requires men’s involvement in childrearing and work-family policies that make it easier for families to handle the challenges of juggling work and family responsibilities. The question we add is whether religion remains a pronatalist force, despite its association with gender traditionalism.6 If religion involves men in families by increasing their likelihood of marriage, decreasing their likelihood of divorce, and motivating them to be involved fathers, its positive effects on fertility may be much greater than its negative effects.

Also note that egalitarianism is not expected to be the new natalism if it means only workplace equality: it is men’s sharing of the second shift—their involvement at home—that is expected to support replacement fertility. Here religious men may have an advantage because their familism fosters involvement.7 Even a traditional gender orientation has been linked to greater paternal involvement, but only among religious men.8 In addition, domestic tasks like diaper changing are not necessarily incompatible with religious concepts like “male headship” that undergo reinterpretation in social contexts, even among those fully devoted to the concepts.9

We know that worldwide, people of faith have more children.10 What we ask is whether this has become less true in low-fertility countries where gender equality may have become increasingly crucial for sustainable fertility.

We start by showing that even in low-fertility societies from the Americas, Europe, East Asia, and Oceania, people of faith have more children. We then test whether that association has weakened over time, as would be expected if religion depresses fertility by promoting traditional gender roles. Religion should have a dwindling pronatalist force if gender egalitarianism has become the dominant determinant of sustainable fertility. In fact, we find that religion supports fertility to a slightly greater degree than in the recent past. Low-fertility countries have experienced a profound retreat from marriage, but religious individuals have retreated from the institution far less. In short, we show that religion maintains an important direct positive association with fertility, plus that its encouragement of marriage may be an important way it contributes to higher fertility levels. We unpack the complex associations between gender roles, religion, and fertility to understand the persistence of faith as a pronatalist force at a time when egalitarianism seems increasingly necessary for replacement fertility.11

People of faith have more children

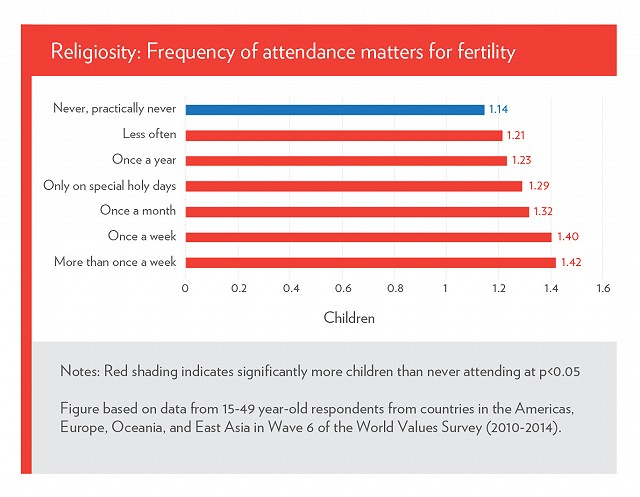

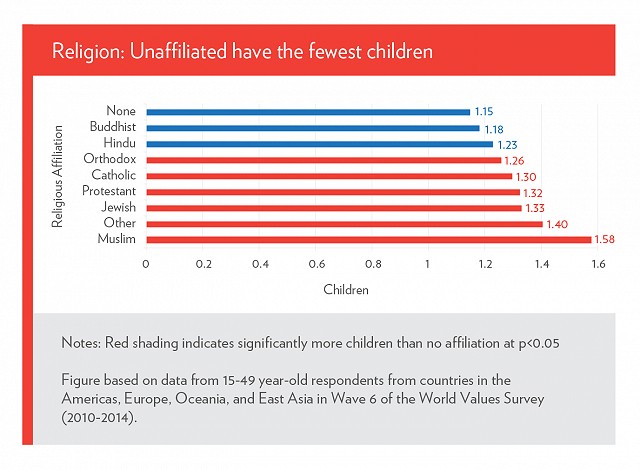

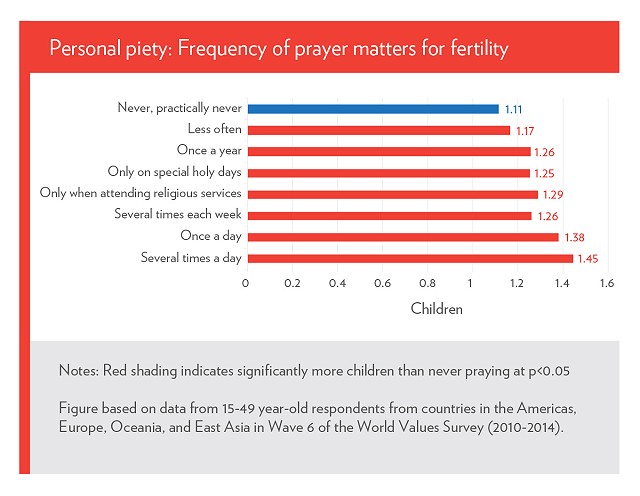

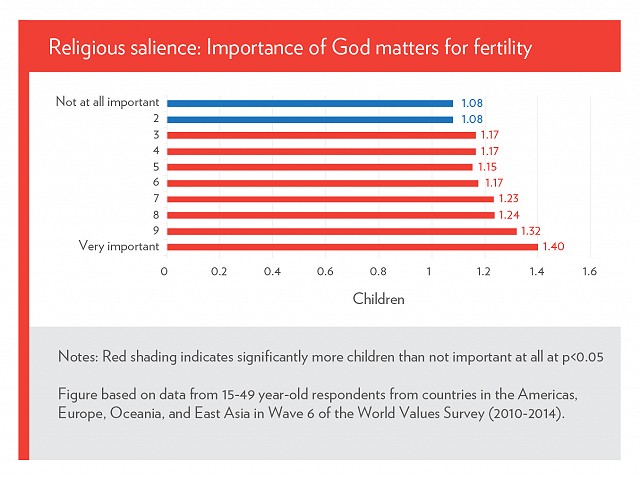

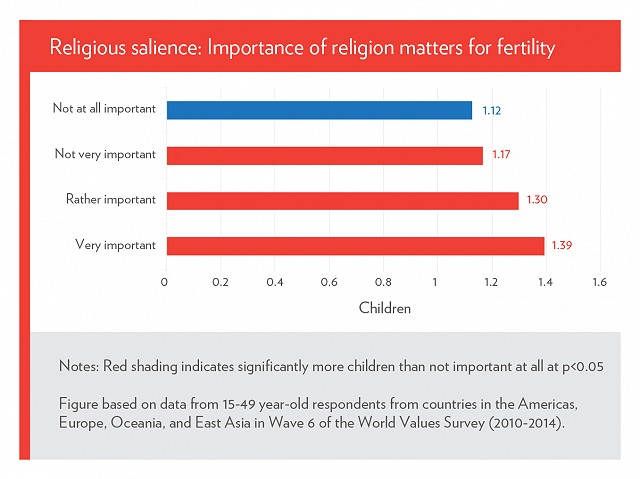

Whether we measure religion by religious affiliation, religiosity (frequency of service attendance), personal piety (frequency of prayer), or religious salience (importance of God and importance of religion), people of faith have more children, even in contemporary low-fertility societies.12 The figures below use data from 15 to 49-year-olds in the most recent wave of the World Values Survey (2010-2014) across countries in the Americas, Europe, Oceania, and East Asia.13 We predicted religious differences in fertility, controlling for age, education, and country. Individual faith matters for how many children people have.

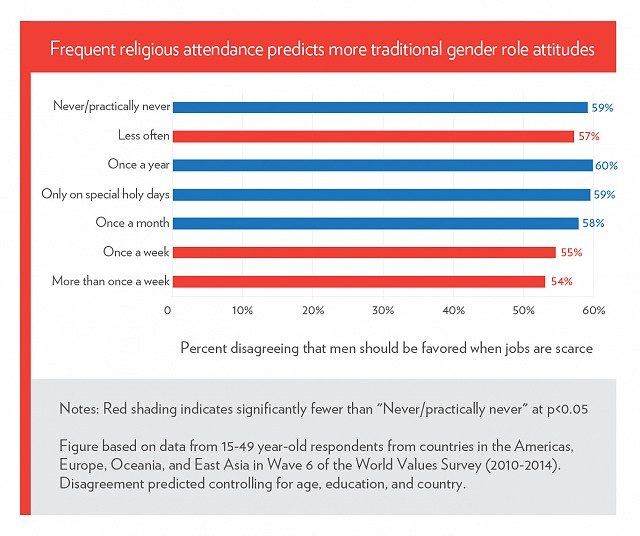

People of faith have more traditional gender role attitudes

We use attendance at religious services as the measure of faith in our subsequent analyses. All measures were strongly related to fertility, and we chose attendance to be consistent with the other chapters of this report that use data from

the Global Family & Gender Survey (GFGS)14 from countries where few people adhere  to religious traditions that do not include corporate worship.

to religious traditions that do not include corporate worship.

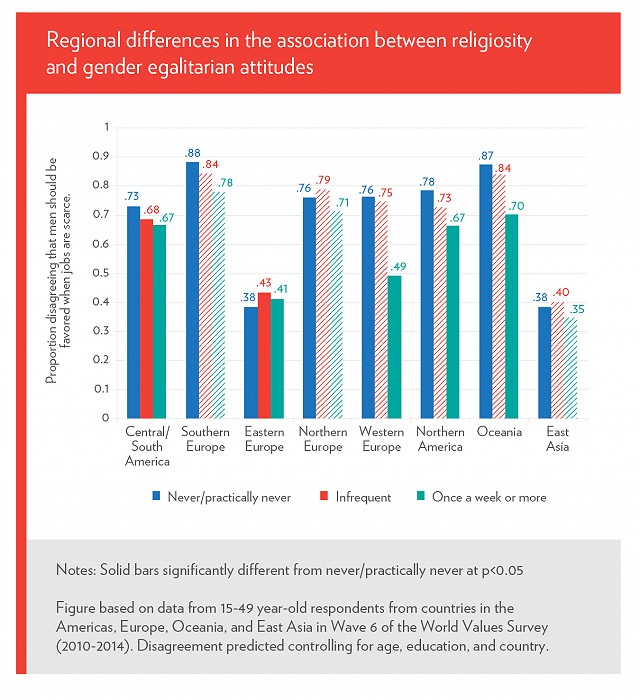

We therefore used service attendance when assessing the relationship between faith and gender traditionalism. Among various options for measuring gender role attitudes, we used responses to the statement: “When jobs are scarce, men should have more right to a job than women.”15 Only respondents who disagreed with this statement fully supported workplace equality; others were likely sympathetic with the idea that men have a greater need to provide for their families than women do. Previous work has shown that people of faith express more traditional gender-role ideology in response to numerous WVS questions, including this one.16 We confirmed that was true among the countries we focus on here: among those who reported attending religious services once a week or more, 53% to 55% endorsed workplace equality compared to 59% of those who never attended (values predicted controlling for age, education, and country).

This means that religious people continue to be more likely to support  traditional gender role ideology at a time when egalitarianism is emerging as an important component of sustainable fertility. It would then seem that faith might have a positive association with fertility despite common gender role ideologies among the faithful suppressing fertility. However, we show in the next section that traditional gender role ideology among individuals was not, in fact, associated with lower fertility.

traditional gender role ideology at a time when egalitarianism is emerging as an important component of sustainable fertility. It would then seem that faith might have a positive association with fertility despite common gender role ideologies among the faithful suppressing fertility. However, we show in the next section that traditional gender role ideology among individuals was not, in fact, associated with lower fertility.

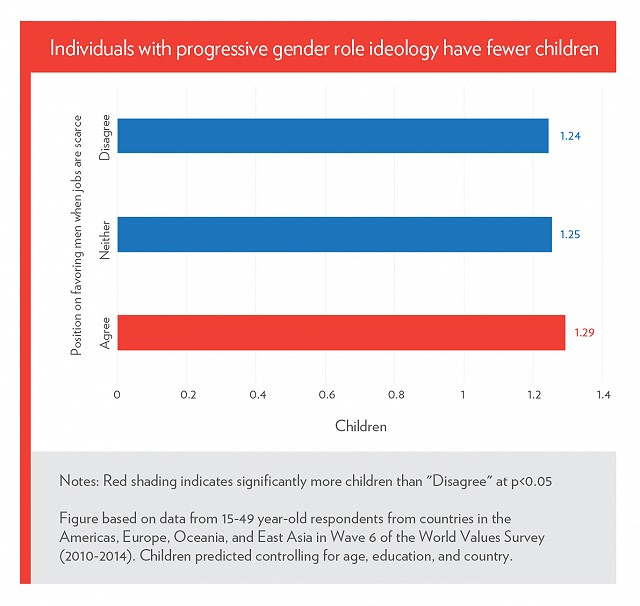

Egalitarian gender role attitudes are associated with fewer children

Individuals who support workplace equality, those who embraced a progressive gender role ideology, actually had significantly fewer children than those who supported favoring men when jobs were scarce.

At first blush, this might seem to discredit the idea that gender equity is “the new natalism”: if progressive families were sharing paid and domestic work equally, this should make having children more practical than in more gender-traditional families, where children increase the length of the “second shift” for working women. However, across our sample, those who agreed with favoring men when jobs were scarce were 23% more likely to be married than those who disagreed.17 This is an important explanation for the higher fertility of people with less egalitarian gender-role attitudes, as married people averaged 0.76 children more than their unmarried peers.18

disagreed.17 This is an important explanation for the higher fertility of people with less egalitarian gender-role attitudes, as married people averaged 0.76 children more than their unmarried peers.18

Moreover, we stress that both traditional gender roles and egalitarianism can be means of coping with the demands of childrearing. Couples adopting more traditional gender roles (she does less paid work) and couples adopting more progressive gender roles (he shares fully in domestic work) would be better positioned to have at least two children than couples in which the woman faces the prospect of an arduous second shift. This perspective

was also reflected in Austrian data showing that couples were more likely to proceed from the first birth to the second if either the woman specialized in childcare or fathers had higher levels of involvement at home.19

Thus, it is not surprising that we have established that a higher frequency of traditional gender role attitudes among the more religious does not reduce their fertility. We have also suggested that gender egalitarianism would support sustainable fertility to a greater extent if it didn’t contribute to the retreat from marriage.20

What about the opposite question: would religion be more pronatalist if it didn’t contribute to gender traditionalism? Here the answer is no. Holding other variables constant, the most religious had 0.27 more children than the least religious, and that gap was not altered by statistically controlling for gender role attitudes.

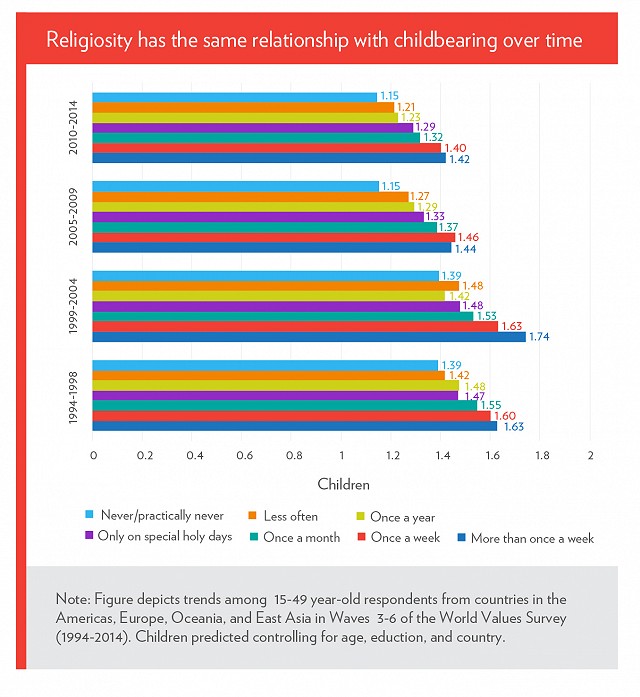

Religion has actually become more important for family size over time

Has the importance of religion as a determinant of fertility dwindled over time? Even though religious people today still have more children, that could be true even if faith had become increasingly less relevant for fertility over time, e.g, if the fertility differential of 0.27 children between those with low and high religiosity shown above was far smaller than in previous decades. Here, we use World Values Survey data since 1994 (Waves 3-6)21 to describe whether the magnitude of the association between religion and fertility has changed across 57 countries in the Americas, Europe, Oceania, and East Asia.

Fertility actually decreased the most among those who do not attend religious services  over time. Overall fertility decreased by 0.25 children between Waves 3 and 6, but the decrease was greater among the less religious, resulting in a slightly wider gap (0.27 children in wave 6 compared to 0.24 in wave 3). The difference is too small to matter statistically, but religion certainly is not becoming less important for fertility, when its influence is growing slightly rather than shrinking significantly.

over time. Overall fertility decreased by 0.25 children between Waves 3 and 6, but the decrease was greater among the less religious, resulting in a slightly wider gap (0.27 children in wave 6 compared to 0.24 in wave 3). The difference is too small to matter statistically, but religion certainly is not becoming less important for fertility, when its influence is growing slightly rather than shrinking significantly.

Marriage is part of this story. Service attendance (a measure for religiosity) became a significantly stronger predictor of marriage from 1994-2004. In wave 3, 50% of those with the lowest self-reported religiosity were married, compared to 59% of those who attended weekly or more—a 9 percentage point spread.22 The retreat from marriage by 2010-14 (wave 6) was evident across all levels of religiosity, but the difference between groups grew enormously: 41% reporting low religiosity versus 57% reporting high religiosity were married.

Religion should have a dwindling pronatalist force if gender egalitarianism has become the dominant determinant of sustainable fertility. Instead, religion became a more important determinant of both fertility and marriage over this  20-year time period. We cannot tell whether this occurred because religion became a more important determinant of marriage, since having children can promote both marriage23 and church-going.24 Nonetheless, the observed change over time is consistent with religion promoting fertility through encouraging marriage.

20-year time period. We cannot tell whether this occurred because religion became a more important determinant of marriage, since having children can promote both marriage23 and church-going.24 Nonetheless, the observed change over time is consistent with religion promoting fertility through encouraging marriage.

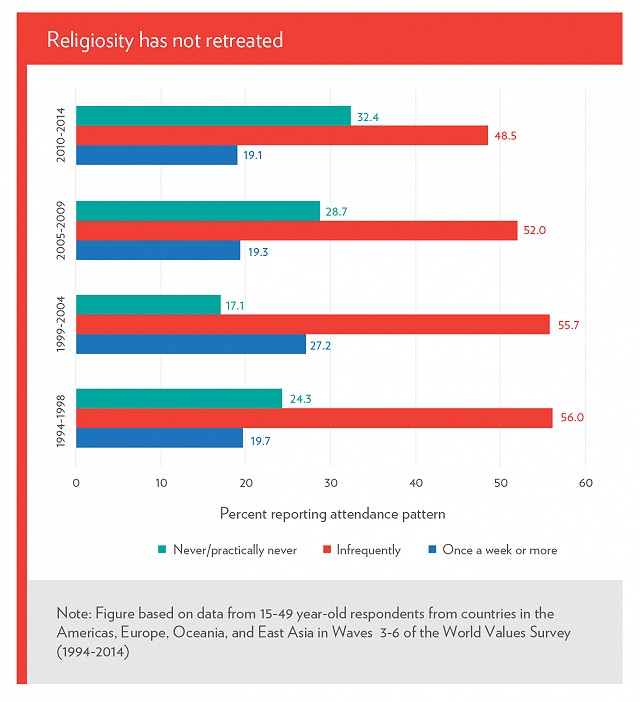

Trends in religious salience over time

There is one final question to be answered in establishing that faith continues to be positively associated with fertility: Are highly religious people becoming an increasingly irrelevant minority with respect to total fertility production? Quite simply, no. Although particular denominations have seen declining numbers, the proportion attending services at least weekly has been fairly consistent across time. The proportion of never-attenders has, in fact, grown over time, but their share has increased at the expense of infrequent attenders rather than regular attenders.

Does religion matter consistently across regions?

Research seeking to understand the determinants of low fertility in low- and middle-income countries is starting to develop as below-replacement fertility is not just emerging but becoming firmly established. Evidence already indicates that gender equity depressed fertility in the past, but seems to be producing a new natalism in  Brazil.25 We repeated our investigation of gender ideology, faith, and fertility separately for North America, Central and South America, Northern, Western, Eastern, and Southern Europe, East Asia, and Oceania to document whether gender ideology and faith interact differently in influencing fertility in these contexts that vary in multiple historical, religious, cultural, and economic ways.

Brazil.25 We repeated our investigation of gender ideology, faith, and fertility separately for North America, Central and South America, Northern, Western, Eastern, and Southern Europe, East Asia, and Oceania to document whether gender ideology and faith interact differently in influencing fertility in these contexts that vary in multiple historical, religious, cultural, and economic ways.

We uncovered marked regional variation, but we still find no evidence of a waning influence of religion on fertility. First, religiosity does not predict gender traditionalism everywhere. In the overall sample, those attending services once a week or more expressed less egalitarian attitudes, but this was not the case in East Asia, Northern Europe, nor Southern Europe. Higher religiosity actually predicts more egalitarian gender role attitudes in Eastern Europe.

Second, the association between religiosity and childbearing that grew only a little for the sample as a whole became significantly stronger in Western and Southern Europe as well as Oceania over time. Nowhere did it weaken significantly.

Finally, there was little evidence for the declining importance of religiosity within regions. Regular attendance became less common in the Americas and Southern Europe between waves 3 and 6; it became more common in Eastern Europe and East Asia.

Thus, gender role attitudes and faith have interacted differently across contexts over time. There is, nonetheless, no region where the pronatalist force associated with  religiosity is tempered by a positive association with gender traditionalism. There were only four regions where religiosity even had a positive association with gender traditionalism: Central/South America, North America, Western Europe, and Oceania. In the latter two regions, the positive association between religiosity and childbearing strengthened rather than weakened over time. In the Americas, the share attending religious services regularly declined over time, but traditional gender role attitudes predicted more—rather than fewer—children.

religiosity is tempered by a positive association with gender traditionalism. There were only four regions where religiosity even had a positive association with gender traditionalism: Central/South America, North America, Western Europe, and Oceania. In the latter two regions, the positive association between religiosity and childbearing strengthened rather than weakened over time. In the Americas, the share attending religious services regularly declined over time, but traditional gender role attitudes predicted more—rather than fewer—children.

Conclusion

Across low-fertility countries in the Americas, Europe, East Asia, and Oceania, highly religious people are not decreasing in number, and neither are their more traditional gender role attitudes impeding their fertility. We have shown higher rates of childbearing among the more religious, and that religion has become more relevant for childbearing during an era when gender equity was supposedly emerging as the new natalism. The “fertility gap” associated with the extremes of religiosity increased 15% from 0.24 children to 0.27 children across the last two decades.

All of this analysis was conducted at the individual level—it did not touch questions about state supports for work-family balance, nor did it interrogate how the prevalence of egalitarian gender role attitudes might benefit even those who do not share them. Nonetheless, we have shown that people of faith contribute toward sustainable fertility in modern low-fertility societies.

The two-child family remains a common ideal,26 but not one that couples, on average,  are realizing. Religious people have previously been shown to be more likely to realize their fertility goals.27 Moreover, married couples are coming closer to the widely shared ideal, and religion is increasingly associated with marriage. The story we tell about religion and fertility is not altered when we integrate gender role attitudes into our narrative. Despite traditional gender role attitudes being somewhat more common among the more religious, both marriage and fruitful marriages are more common among the religious. If anything, religion is gaining salience as a determinant of birth rates. In other words, faith remains an important force for natalism in the developed world.

are realizing. Religious people have previously been shown to be more likely to realize their fertility goals.27 Moreover, married couples are coming closer to the widely shared ideal, and religion is increasingly associated with marriage. The story we tell about religion and fertility is not altered when we integrate gender role attitudes into our narrative. Despite traditional gender role attitudes being somewhat more common among the more religious, both marriage and fruitful marriages are more common among the religious. If anything, religion is gaining salience as a determinant of birth rates. In other words, faith remains an important force for natalism in the developed world.

Data and Methods

Findings in this report are based primarily on two sources: the World Values Survey (WVS) and the Global Family and Gender Survey (GFGS).

The WVS started in 1981, and there are new waves every five years. Many questions are identical across waves. Participating countries comprise almost 90 percent of the world’s population. The seventh wave (2017-2019) is still in the field, and our report utilizes data from the first six waves. See www.worldvaluessurvey.org for a description of the global network of social scientists that makes the WVS possible. Their sampling methodology is detailed there as well.

The 2018 Global Family and Gender Survey (GFGS) was conducted September 13-25, 2018, by Ipsos Public Affairs (formerly GfK) on behalf of The Wheatley Institution and the Institute for Family Studies. The survey used samples of adults ages 18 to 50 from KnowledgePanel® in the United States and Toluna (opt-in panels) in Australia, France, Ireland, United Kingdom, Canada, Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru. Ipsos randomly recruited KnowledgePanel® members through probability-based sampling, and households were provided with access to the Internet and hardware if needed. Toluna is one of the largest and most diverse qualified online panels in the world. Individuals were recruited in real-time from a network of websites with which Toluna had developed referral relationships. This combination of sampling strategies means that, after weighting, the GFGS data from the United States are nationally representative of the 18-50-year-old population, but the GFGS data from other countries are not. Samples for other countries were weighted to match the distributions of age, gender, education, and region of the national population ages 18 to 50. We refer to levels of statistical significance in our description of the results to highlight effects of meaningful size throughout. This is technically correct for the United States sample, but it is only descriptive for the other countries that did not have probability samples.

Survey interviews were conducted online in English, Spanish, and French languages (depending on the languages used in each country). A total of 16,474 interviews were completed. Sample sizes for each country are as follows: Argentina—668, Australia— 2,420, Canada—2,200, Chile—1,240, Colombia—620, France—1,215, Ireland—2,420, Mexico—677, Peru—645, United Kingdom—2,344, and United States of America—2,025. Our pooled regressions are most heavily influenced by Mexico and the United States because we weighted countries according to their relative population sizes.

For this 2019 World Family Map report, we addressed questions of relationship quality (Chapters 2 and 3) using 9,566 men and women in heterosexual relationships (6,104 married and 3,462 cohabiting). Men and women in LGBTQ relationships (n=589) were not included in the analyses. Processes of selection into and out of religious participation are likely to vary greatly with sexual orientation, and patterns of religiously assortative mating may also vary with sexual orientation.

Both chapters use the same definitions of couple religiosity and the same control variables when predicting outcomes.

Couple religiosity:

- Shared secular couples are married or cohabiting men and women who report they “never” attend religious services and that their partner or spouse is “as religious” or “less religious” than they are.

- Less/mixed religious couples are defined as those who report that both they and their partner engage in fairly minimal religious service attendance (once a month or less), plus respondents who attend religious services regularly themselves, but have partners who are less religious than they are. Of these less/mixed religious couples, 87% reported shared minimal religious attendance, while 13% were couples where the respondent was a regular church attender partnered with a less devout spouse or partner.

- Highly religious couples are respondents who attend religious services regularly (2-3 times a month or more) and whose spouse or partner is as religious or more religious than they are.

Control variables:

- Individual characteristics at interview

- Gender is self-reported.

- Age is measured in continuous years, 18-50.

- Education uses four categories: less than high school; high school graduate; some tertiary education (whether college/university or vocational); and a completed degree (bachelor’s or higher).

- Race/ethnicity. US sample only. Five categories: Hispanics and four categories of Non-Hispanics (White, Black, Other, and two or more races).

- Individual history

- Native-born status.

- Parental relationship is whether or not the respondent lived with both biological parents at age 16.

- Ever divorced measures whether the respondent has personally experienced divorce.

- Couple/household/area characteristics

- Legal status of current union is married or cohabiting.

- Relationship duration is how long the couple has been together in months (with durations of longer than 12 months reported in years and converted to months).

- Presence of children means that a child under age 18 lives with the couple, regardless of that child’s relationship to either of them.

- Financial circumstances is measured by the respondent’s subjective report using four categories: Don’t have enough to meet basic expenses; Just meeting basic expenses; Living comfortably; and Living very comfortably.

- Country of residence.

- Place of residence is defined as rural or urban.

We used a linear regression model with all controls predicting the overall relationship quality index in Chapter 2. All of the other outcomes in Chapters 2 and 3—satisfaction with sexual relationship with current partner (strongly agreeing)1, joint decision-making, victim of intimate partner violence, perpetrator of intimate partner violence, and infidelity—used logistic regression, again with the full set of controls. Statistical significance is estimated by the p-values (p<0.05, two-tailed tests) of the logistic regression coefficients.

For all three chapters, our figures show predicted probabilities from our regression models with control variables set at their means. Full regression tables for all chapters are available at http://ifstudies.org/the-ties-that-bind.

Footnotes

1 J. Kotkin, A. Shroff, A. Modarres, & W. Cox, The Rise of Post-Familialism: Humanity’s Future (Singapore: Civil Service College, 2012).

2 N.B. Ryder (1967), “The Character of Modern Fertility,” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 369, no. 1 (1967): 26-36.

3 United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, “World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision,” as found at: https://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/

4 Even research emphasizing that overall development leads to reversals in fertility decline nonetheless notes that the absence of institutions that facilitate work– family balance and gender equality might explain countries that are exceptions to the rule. See, for example: M. Myrskylä, H.-P. Kohler, & F. C. Billari, “Advances in Development Reverse Fertility Declines,” Nature, 460, no. 7256 (2009): 741.

5 F. Goldscheider, E. Bernhardt, & T. Lappegård, “The Gender Revolution: A Framework for Understanding Changing Family and Demographic Behaviour,” Population and Development Review, 41, no. 2: (2015): 207-239.

6 R. Inglehart & P. Norris, Rising Tide: Gender Equality and Cultural Change Around the World, (Cambridge University Press, 2003). L. Schnabel, “Religion and Gender Equality Worldwide: A Country-level Analysis,” Social Indicators Research, 129, no. 2 (2016): 893-907. S. Seguino, “Help or Hindrance? Religion’s Impact on Gender Inequality in Attitudes and Outcomes,” World Development, 39, no. 8 (2011): 1308-1321.

7 F. Goldscheider, C. Goldscheider, & A. Rico-Gonzalez, “Gender Equality in Sweden: Are the Religious More Patriarchal?” Journal of Family Issues, 35 no. 7 (2014): 892-908.

8 W. B. Wilcox, Soft Patriarchs, New Men: How Christianity Shapes Fathers and Husbands, (University of Chicago Press, 2004).

9 M. L. Denton, “Gender and Marital Decision Making: Negotiating Religious Ideology and Practice,” Social Forces, 82, no. 3 (2004): 1151-1180.

10 C. Hackett, M. Stonawski, M. Potančoková, B.J. Grim, & V. Skirbekk, “The Future Size of Religiously-Affiliated and Unaffiliated Populations,” Demographic Research, 32, no. 1 (2015): 829-842.

11 B. Arpino, G. Esping-Anderson, & Lea Pessin, “How Do Changes in Gender Role Attitudes Towards Female Employment Influence Fertility? A Macro-level Analysis,” European Sociological Review, 31, no. 3 (2015): 370-382.

11 B. Arpino, G. Esping-Anderson, & Lea Pessin, “How Do Changes in Gender Role Attitudes Towards Female Employment Influence Fertility? A Macro-level Analysis,” European Sociological Review, 31, no. 3 (2015): 370-382.

12 Almost all of the countries in our sample had fertility below replacement (2.1 children per woman) in the most recent WVS wave, but the number of children shown in our graphics is still lower because many respondents were still in their childbearing years and would ultimately have more children.

13 North America: Mexico, United States; Latin America and the Caribbean: Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Trinidad and Tobago, Uruguay; Northern Europe: Estonia, Sweden; Western Europe: Germany, Netherlands; Southern Europe: Slovenia, Spain; Eastern Europe: Azerbaijan, Armenia, Belarus, Georgia, Poland, Romania, Russia, Ukraine; Oceania: Australia, New Zealand; East Asia: China, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore (Hong Kong omitted because it did not collect children ever born).

14 A full description of this survey will be provided in Chapter 2.

15 A measure of attitudes favoring workplace equality lacks explicit reference to our variable of greatest interest—men’s involvement at home. It is, however, the same variable that Arpino et al. (2015) used when they showed a curvilinear relationship between gender role attitudes and fertility at the national level, i.e., that greater acceptance of workplace equality was correlated with lower fertility only up to a point, after which higher levels predicted higher fertility. Our sensitivity analysis showed that our results did not depend on our choice of gender attitudes measures, though none of the alternatives directly measured men’s involvement at home.

16 S. Seguino, “Help or Hindrance? Religion’s Impact on Gender Inequality in Attitudes and Outcomes,” World Development, 39 no. 8 (2011): 1308-1321.

17 Controlling for age, education, and country.

18 Controlling for age, education, and country.

19 F. Luppi, “When Is the Second One Coming? The Effect of Couple’s Subjective Well-Being Following the Onset of Parenthood,” European Journal of Population, 32, no. 3: (2016): 421-444. For similar findings from the U.S., see also: B. M. Torr & S.E. Short, “Second Births and the Second Shift: A Research Note on Gender Equity and Fertility,” Population and Development Review, 30, no. 1 (2004): 109-130.

20 Findings from the U.S. and Sweden indicate that men’s egalitarianism contributes to the stability of marriage (Kaufman 2000; Oláh 2001), but in our data, less marriage seems to dominate any affect from more stable marriage.

21 We do not use data from the first WVS wave, 1981-1984, because it did not ask the religious salience question; in wave 2, only 2 countries had comparable education data.

22 Values predicted controlling for age, education, and country.

23 B. Perelli-Harris, M. Kreyenfeld, W. Sigle-Rushton, R. Keizer, T. Lappegård, A. Jasilioniene, et al. “Changes in Union Status During the Transition to Parenthood in Eleven European Countries, 1970s to Early 2000s,” Population Studies, 66, no. 2 (2012): 167-182.

24 C. Schleifer & M. Chaves, “Family Formation and Religious Service Attendance: Untangling Marital and Parental Effects,” Sociological Methods & Research, 46, no. 1 (2017): 125-152.

25 H.C. Castanheira & H.P. Kohler, “Social Determinants of Low Fertility in Brazil,” Journal of Biosocial Science, 49, no.1 (2017): S131-S155.

26 T. Sobotka & E. Beaujouan, “Two Is Best? The Persistence of a Two-child Family Ideal in Europe,” Population and Development Review, 40, no. 3 (2014): 391-419.

27 D. Philipov & C. Berghammer, “Religion and Fertility Ideals, Intentions, and Behaviour: a Comparative Study of European Countries,” Vienna Yearbook of Population Research, 5 (2007): 271-305.