Highlights

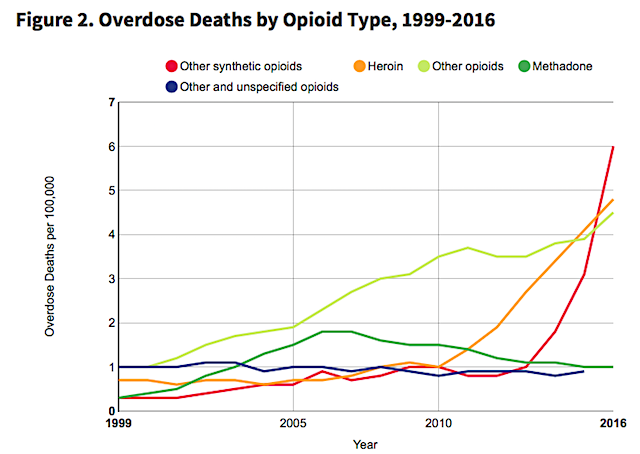

A new report from Utah Senator Mike Lee’s Social Capital Project takes a deep dive into the available data on opioid addiction and offers a bleak, but sadly, unsurprising look at the present disaster. Opioid-related deaths quadrupled in the years between 1999 and 2015, the report says. In the single year 2015 and 2016, the number of deaths from fentanyl and other synthetic opioids more than doubled. Indeed, opioids are now the top cause of accidental death for all Americans under age 50 and “have surpassed the all-time peaks of annual deaths caused (individually) by car crashes, H.I.V, and guns.”

Source: Social Capital Project, "The Numbers Behind the Opioid Crisis," October 2017.

The numbers are in line with the ghastly details in journalistic accounts: Mobile trailer morgues, jammed small town emergency rooms, a grandmother and her partner passed out in a car as her grandchild sits quietly behind them – for safety reasons –strapped in a car seat. This, as Chris Caldwell noted in First Things, is the real “American Carnage.”

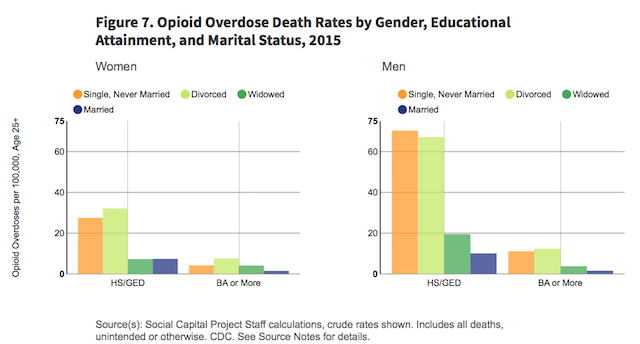

Senator Lee’s new report also reveals a less familiar finding—though it may not surprise those of us who study family matters: addiction is most common among young single and divorced men. Sixty-one percent of the adult population is married; that population makes up 28% of opioid overdose deaths. Never-married and divorced adults are a much smaller percentage of the population, 32% to be precise, but accounted for—take a deep breath—71% of opioid deaths.

Source: Social Capital Project, "The Numbers Behind the Opioid Crisis," October 2017.

While family breakdown had long seemed to be a crisis largely confined to poor minority groups, family scholars have come to realize high divorce and nonmarital birth rates in the white working class. In 1970, 70% of moderately educated adults were in intact first marriages, but by the 2000’s only 45% were. By the years 2006-08, 44% of children in that demographic were born to unmarried mothers, compared to 13% in 1982. As of 2013, 30% of all white babies arrived home from maternity wards to unmarried parents; the great majority of them among the working class.

Given what we know about how single men fare on a variety of measures compared to their married peers, it makes sense that they would be more likely to succumb to America’s current pharmaceutical scourge. All in all, married men live longer and they are less likely to commit suicide. They typically take fewer risks than single men: they have fewer car accidents. get into fewer fights, and more generally engage in less thrill-seeking behaviors, including taking drugs. (Married men in treatment for addiction are also less likely than singles to relapse.) Some of this is no doubt age-related: young men are more likely to be single. But as the age of marriage has risen and as the number of men—and women—who are not married has increased, single status is no longer largely limited to young twenty-somethings—and neither are some of its associated risks.

Adding to the social isolation of young single men is their poor job prospects in a postindustrial economy. In the past, the blue-collar workplace was not just somewhere you went every day to earn a paycheck; it was also a place you could be seen and known, where you could make friends or wave to a new neighbor, and find baseball or bowling leagues. Now, with historic numbers of working-aged men completely cut off from the labor market, and many of those who are working struggling through irregular hours or churning through temporary jobs, the solidarity of the factory floor has given way to the atomization of the gig economy, or even worse, freedom with nothing left to lose.

How are all of these trends related? Did a lousy economy lead to fewer intact families because men were no longer “marriageable”? Was it a poor economy or family breakdown— or both—that led more people to look to opioids for sustenance? Do women, in particular, avoid marrying the sort of man who might become addicted? To put it a little differently, is marriage itself protecting people from addiction and overdose, or are potential addicts the sort no one wants to marry or who themselves can’t make a commitment?

The exact causal dynamic between a poor labor market, family breakdown, and now the opioid crisis will no doubt be a subject of intense scholarly dispute for years to come. But whatever explanation wins, the new reality is that many white working-class communities now resemble the inner city ghettoes of the 70’s and 80 (though, at least for the time being, violent crime remains at manageable levels.) Fractured families, idle men, drug-addicted parents, babies born with opioids in their systems, neglected children. State foster care systems are overwhelmed. Maine alone had a 45% increase in children in foster care in the five years between 2011 and 2016. Fourteen states experienced a 25% rise or more between 2011 and 2015.

“The Numbers Behind the Opioid Crisis” is the second publication on the subject from Senator Lee’s Social Capital Project. The purpose of the unusual project is “to better understand the health of our associational life,” meaning, families, communities, workplaces, and congregations. In many places in the United States that health is poor. So is the prognosis.

Kay S. Hymowitz is the William E. Simon Fellow at the Manhattan Institute and a contributing editor of City Journal. She writes extensively on childhood, family issues, poverty, and cultural change in America.