Highlights

- Increasingly postponed marriage can account for at least half of the increase in the fertility gap over the last decade and for virtually 100% of the increase since 2000. Post This

- For two working-class people with similar incomes, there’s a very real tax on marriage. Post This

- To make family life more achievable: fix the massive government bias against marriage and especially working-class marriage. Post This

Editor's Note: The following essay is an edited version of IFS research fellow Lyman Stone's oral testimony before the Joint Economic Committee on September 10, 2019.

Thank you, it’s an honor to be here today to testify on topics that are important to American families. I’m affiliated with the American Enterprise Institute and the Institute for Family Studies, however for my testimony today, the views offered are solely my own.

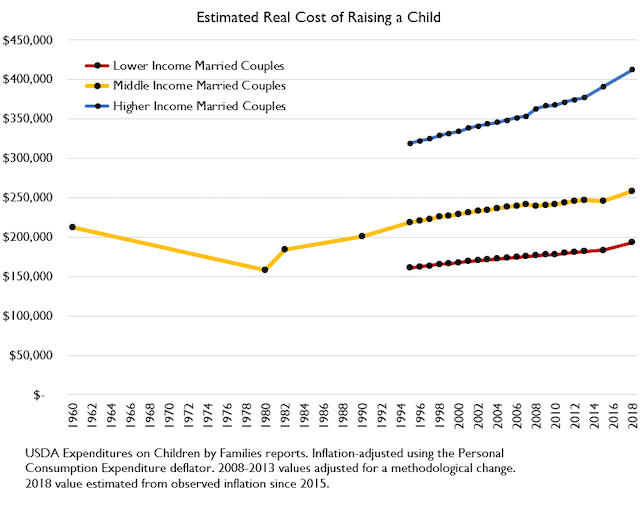

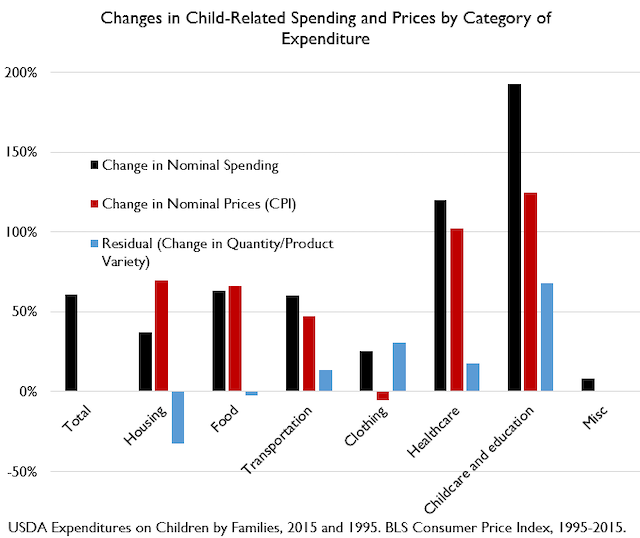

Most of my written testimony discusses concrete questions of family affordability. The upshot is: contrary to popular narratives, child-rearing in America is not really any more expensive than in the past.

Some elements of raising a family have gotten more expensive, but the evidence suggests that the problem facing families is not simply a budget crunch.

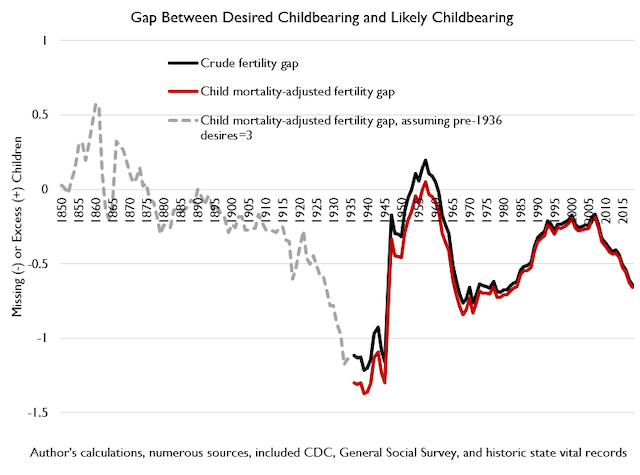

According to a wide variety of surveys, the average American woman says she wants to have around 2.3 to 2.5 children. This value has been approximately stable for 30 years. And yet, if current birth rates hold, the average young American woman today will only end up having 1.7 children. That means that for every 10 women in America, there will be 6 missing children. This is a new problem: from 1990 to 2007, the fertility gap was consistently just one third as large.

So what’s going on? Instead, of “affordability,” we should discuss “achievability.” What is holding people back from having the family they reliably say they want in surveys?

The answer is basically “marriage.” Increasingly postponed marriage can account for at least half of the increase in the fertility gap over the last decade and for virtually 100% of the increase since 2000.

But incentivizing marriage is a tricky question in a diverse society. Americans are justifiably uncomfortable with being lectured about getting hitched, by anyone, especially the Federal government!

But luckily, there are some good policy options available.

First of all, it must be said, the federal government already has a marriage policy. And that policy is this: working-class people should not get married, but middle-class and wealthy people should. This is the policy stance of the tax code, of our welfare programs, of almost everything the government does. The tax code gives you a handy marriage bonus if you have a CEO in the family, as their spouse is unlikely to earn an equivalent amount, and our tax brackets are of greatest benefit to families with the most lopsided spousal incomes. But if you get the EITC, getting married could reduce your benefit by thousands of dollars. For two working-class people with similar incomes, there’s a very real tax on marriage. In my written testimony, I show how the marriage penalty can amount to 15% or even 25% of a family’s income. It’s no mystery why working-class Americans are getting married less.

To be clear, the problem here is not “government benefits” per se but their eligibility rules that discourage working-class Americans from marrying. And the result is neighborhoods with scattered families, inconsistent fathers, overworked mothers, and diminished opportunity for children. And, additionally, fewer kids overall.

So there’s a very real way to make family life more achievable. Fix the massive government bias against marriage and especially working-class marriage.

The second response to the “marriage first” explanation for decreased family achievement is to reconsider our justifications for policies like the Child Tax Credit. The justification for the Child Tax Credit is not that parents are inherently cash-strapped, but rather that parenting is inherently valuable to society.

In other words, we should have a parenting wage because parenting is important work, and workers deserve to be paid. How we provide such a wage may vary, but we, as a society, should treat parents more generously than we presently do, and in a way that explicitly communicates to parents that we see parenting as worthy labor.

When societies provide a “parenting wage,” the fertility gap shrinks! Now, if there’s not also a change in marriage norms and behavior, fertility rates won’t rise by a lot. So the best strategy is a one-two punch: for family achievability to improve in America, it’s vital that we, 1) end penalties for working-class marriage, while 2) increasing our social commitment to the work of parenting by providing a parenting wage. And whatever happens to fertility rates, the children who are born are born into a society of greater opportunity and healthier families—one that engages in a valuable public catechesis: parenting matters.

Lyman Stone is a Research Fellow at the Institute for Family Studies, and an Adjunct Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute.