Highlights

If I had to describe my family life when I was a child, it would be complicated. I am the only child of my parents, who divorced when I was two. By the time I turned five, both my parents had remarried. From their new unions, I gained five half-siblings—three from my father’s marriage and two from my mother’s. Her new husband also had two sons from a previous union, so until they divorced, I also had two step-brothers. I love my half-siblings very much, but our relationship has sometimes been complicated by the reality that I have a different biological mother and father. Although both my parents went to great lengths to blend me into their new families, I always felt like a bit of an outsider in both.

I grew up in a community where this type of family complexity was common: many of my relatives also had remarried parents, half-siblings, step-parents, and distant (or absent) biological fathers, and some of my family members grew up to form complex families of their own. Perhaps that’s why I did not consider it all that unusual for my parents to “have biological children with more than one person”—a phenomenon family scholars call “multiple partner fertility” or MPF—nor did I connect the complexity of my family to the instability I experienced as a child.

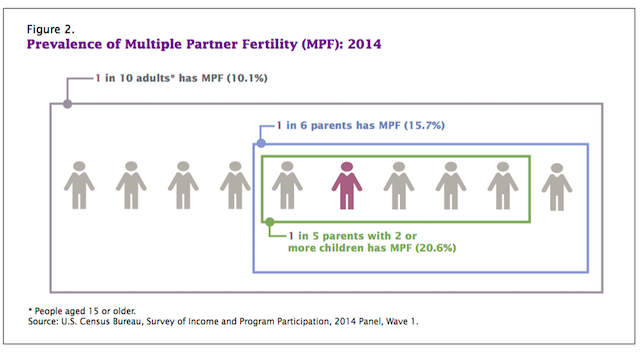

While MPF is certainly not new, it is increasingly common today due to the rise in divorce and nonmarital childbearing. Just how common has been difficult for researchers to track, mainly because of the complexity and instability associated with it. To better estimate its prevalence, a new U.S. Census Bureau research brief relies on data from the 2014 Survey of Income and Program (SIPP) Participation, the first nationally-representative survey to include a specific question about MPF.

The SIPP allowed the Census Bureau to examine the prevalence of MPF among different populations: adults (age 15 and older), parents of biological children, parents of two or more biological children, mothers and fathers, and cohabiting and married-parent families. The report notes that MPF is defined by biological children, not by custody, the living arrangements of the child, or the child’s age, and includes single, divorced, married, and cohabiting parents.

According to the report, one in 10 U.S. adults, or 10.1 percent of individuals aged 15 and older, has experienced MPF. The prevalence of MPF increases among parents (“adults with biological children”), where 15.7 percent have MPF. It is even higher (and possibly more accurate) among parents of two or more biological children: 20.6 percent have MPF (see figure below). Among men and women with two or more children, 21.6 percent of mothers have MPF, while 19.3 percent of fathers have MPF.

A Profile of the MPF Parent

While MPF does occur after divorce and remarriage, it is more common among unmarried couples. According to the Census report, 19.2 percent of married opposite-sex couples include “at least one partner” who has a biological child from another union, while in 27.6 percent of cohabiting opposite-sex couples, "one or both partners" has MPF.

A 2014 study by Karen Benjamin Guzzo found that men and women with MPF also tend to start having children earlier in life, and are significantly less likely to have an intended first birth and to have their first birth in a co-residential union. Moreover, a study by University of Wisconsin sociologist Marcia Carlson and Frank Furstenberg found that MPF is more common among low-income and less educated parents, Black/non-Hispanic men and women, parents who grew up in single-parent families, and fathers who have been incarcerated.

What Impact Does MPF Have on Children?

An extensive body of research has linked MPF with negative child well-being. One reason is that MPF can diminish a parent’s ability to parent well. For example, a recently published study by Paula Fomby found that mothers with MPF are more likely to experience depression and parenting stress than mothers who have biological children with only one father.

As to why mothers with MPF tend to be more stressed and prone to depression, it might be partly due to how having children with multiple partners can divide a mother’s loyalty. If her new partner mistreats her child from a previous union, or if the child and stepdad simply do not get along, the mother is understandably conflicted. If she sides with her child over her new man, it could cause problems between them, or, worse, result in her other children (the biological kids of her new partner) losing their father. Sadly, I’ve watched this division of loyalty lead stressed-out mothers to stay too long with men who are a danger to at least one of their children.

Another consistent finding related to child well-being in MPF families is that these children tend to have less involved fathers. In a presentation about her study, Marcia Carlson explained that the MPF fathers often spend less time and resources on their biological children from former unions:

Some people have called this 'swapping families,' the fathers have moved on in a certain way. There's less incentive to invest in your kids when you don't live with them; you don't know how the money you give is spent; you are not involved with your children daily.

Sometimes, a father’s relationship with his biological child is inhibited by the child’s mother and her new partner. I’ve seen mothers push their child’s biological father away (often under pressure from their new boyfriend or husband) so their partner can be the child's "new daddy." In addition to disrupting the child’s vital connection to his or her biological father, this can backfire when the mother’s new relationship ends, or if her partner does not end up being the stepfather she hoped he would.

For children, MPF is associated with a greater risk of behavior problems, poor academic performance, adolescent drug use, and depression. A recent study by Cynthia Osborne and Paula Fomby using data from the Fragile Families and Child Wellbeing Study found that MPF was “robustly related to self-reported delinquency and teacher-reported behavior problems” among children born to married mothers.

Another study found that the presence of half and step-siblings in a family is associated with a greater risk of depression, delinquency, and poor academic performance for children. Finally, a study by Karen Benjamen Guzzo and Cassandra Dorius found that a mother’s MPF has a “significant direct and moderated effect on adolescent drug use and sexual debut net of cumulative family instability and exposure to particular family forms like marriage, cohabitation, and divorce.”

Of course, MPF does not impact all children in the same way, and not every child growing up in an MPF family will experience these adverse outcomes (thankfully, I avoided most of them). But as I saw in my family, MPF can complicate parent and sibling relationships.

When we read that 1 in 6 U.S. parents has biological children with more than one person, we should remember the children behind those numbers—children growing up in often unstable families where they must navigate the complexities of their parents’ romantic relationships and the birth of half-siblings, while also potentially dealing with the loss of relationship with their other biological parent, often the father. Multiple partner fertility might be a reality for many families today, but it is one with troubling implications for the social and economic well-being of future generations.