Highlights

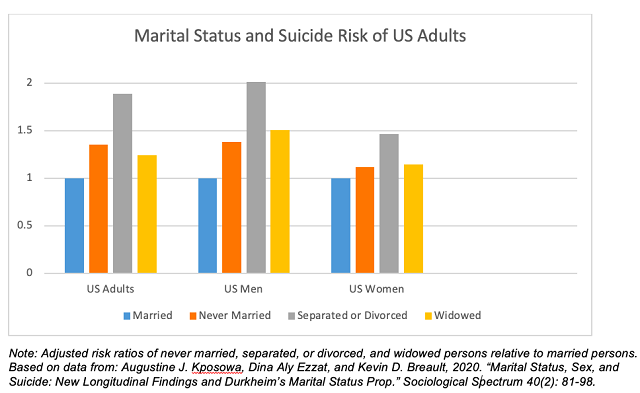

- In the US, the risk of suicide for separated or divorced people is nearly twice that for married people. Post This

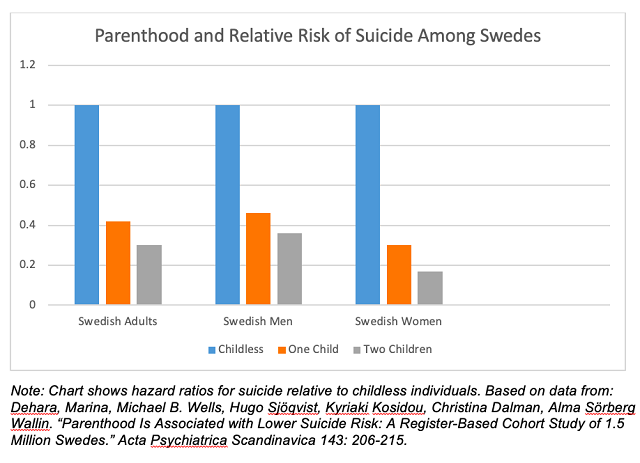

- A study of a birth cohort of 1.5 million Swedes found that parenthood lowered suicide risk for both men and women, and that having two children lowered the risk more. Post This

- While abusive or dysfunctional relationships are dangerous, the evidence shows that the bonds of marriage and parenthood generally reduce the risk of suicide. Post This

Life expectancy in the U.S. has declined, driven by so-called deaths of despair, including suicide. Between 1999 and 2018, the suicide rate rose by 35%, from 10.5 per 100,000 to a peak of 14.2 per 100,000 before declining slightly in 2019. Suicide now kills about 45,000 Americans per year. The increase brings new attention to the social factors that might shape a person’s decision to end their own life. Among these, family relationships stand out.

For over a century, at least since the pioneering work of French sociologist Emile Durkheim, we have known that social bonds—or their absence—plays a crucial role in suicide. Durkheim famously found married people had lower rates of suicide than the unmarried and that parents had lower rate than the childless. He explained this as part of a larger pattern in which people’s integration into social relationships and institutions acted as a protective factor against suicide. He claimed that the bonds of social life, including family life, made the suicidal inclination less likely to arise in the first place. And if it did arise, it gave people more reasons to resist it–something bigger than themselves to justify life’s struggles.

Modern research shows that Durkheim’s idea about the protective effects of family life is still largely accurate, though with a few wrinkles and caveats. One caveat is that the quality of family relationships matters. As I have argued elsewhere, various sorts of interpersonal conflict are more likely to cause suicide when they occur within the family, and stormy or abusive relationships increase the danger of suicide. In some times and places, this is a big enough problem as to make marriage a risk factor, especially for women. For instance, in such places as Afghanistan, marriage is often a kind of harsh patriarchy that results in frequent and severe domestic violence. Some married women in these countries increasingly kill themselves by burning, a dramatic means chosen to both escape their suffering and protest their treatment. Where forced marriages and abuse by husbands and in-laws is common and largely accepted, the age of first marriage carries a high suicide risk for women.

This sort of extreme is much rarer elsewhere. Studies of various countries in Europe, Asia, and the Americas find that marriage generally has a protective effect. Evidence for this includes the results of large-scale longitudinal studies that track hundreds of thousands, or in some cases millions, of individuals over time. For instance, a national-register study of all Norwegians between the ages of 35 and 54 found that risk of suicide was significantly lower among married men and women than among their unmarried counterparts. Likewise, an analysis of over one million US adults included in the National Health Interview Survey found that never-married persons were 48% more likely to commit suicide than those who were either married or living with a partner. Another study of nearly a half-million US adults found similar results, as seen in the chart below.

Notably, this study found that protective effect of marriage was only strong and statistically significant for men. Marriage, it seems, is especially important in men’s lives. Given that American men are about four times more likely than women to commit suicide, it has a substantial effect on suicide overall.

Marital stability also matters. Whoever said “it is better to have loved and lost than to never have loved at all” might never have tried it. Losing a spouse to death raises the risk of suicide, such that widowed people have higher rates than those whose spouses are still alive. But being widowed is less dangerous than being divorced: Studies commonly find that the divorced and separated have higher suicide rates than any other marital status. In the U.S., the risk of suicide for separated or divorced people is nearly twice that for married people. This is not merely a selection effect, with depressed individuals more likely to have unsuccessful marriages. Research that examines the timing of suicide reveals that the period just after the divorce, or the initial separation, is most dangerous. Likewise, aggregate changes in the divorce rate predict later changes in the suicide rate. Notably, despite the fact that women initiate most divorces, divorce increases suicide risk for both men and women. But just as marriage often has greater benefits for men, divorce and widowhood hit them particularly hard.

The effect of parenthood is less studied, but here, too, research is generally consistent with the protective effect of family integration. In a national study of Norwegians, having at least one child led to a significant decline in the odds of suicide. A study of a birth cohort of 1.5 million Swedes found that parenthood lowered suicide risk for both men and women, and that having two children lowered the risk more than only having one. Those with two children had a risk of suicide 70% less than their childless peers. The chart below, based on data from this study, shows this dramatic relationship.

We have less information on the role of parenthood in U.S. suicide, though there is evidence that having a larger family is associated with lower suicide risk: One study estimates that each additional member reduced the subject’s suicide risk by 15 percent. And being a parent might be especially protective for women. A large-scale comparison of suicide fatalities to matched controls in Denmark found that having children lowered the suicide risk for both sexes, but more so for women. Similarly, research in Australia found that having children was more protective for women.

While abusive or dysfunctional relationships are dangerous, the evidence shows that the bonds of marriage and parenthood generally reduce the risk of suicide. One upshot of these findings is that suicide prevention need not be limited to providing mental health services. Policies that encourage family formation, family stability, and family harmony are, in effect, policies that prevent suicide.

Jason Manning is Associate Professor of Sociology at West Virginia University, and author of Suicide: The Social Causes of Self-Destruction.