Highlights

Senators Michael Bennet (D-CO) and Sherrod Brown (D-OH) are touting a new piece of legislation: the American Family Act of 2017. It represents a decidedly liberal approach to boosting the Child Tax Credit (CTC), a goal many conservatives share.

Today, the credit is worth $1,000 per child. It phases out for the upper-middle class and the wealthy, and it’s “refundable” only in certain circumstances, meaning that low-income families can’t always get it if they don’t have $1,000 worth of tax liability to offset.

The American Family Act would inject the current CTC policy with a truckful of steroids. The credit would be worth $3,600 annually for each child under age 6 and $3,000 for those 6 to 18—and while it would still phase out for higher earners, it would be fully refundable, no strings attached, for the poor. It would be paid out monthly instead of once a year, and it would automatically adjust with inflation.

To hear the bill’s sponsors tell it, the legislation will slash poverty and make kids better off in countless ways without causing any harm. I myself am a fan of expanding the CTC and making it refundable, but this particular formula for doing so raises serious concerns about unintended consequences.

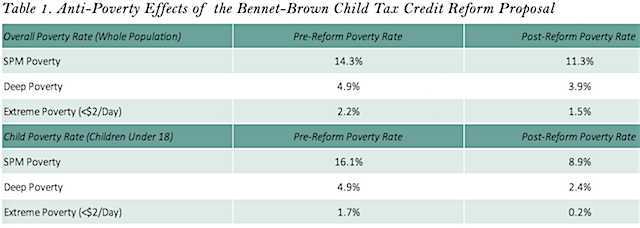

Let’s start with the effects on poverty, a major selling point. The sponsors had Christopher Wimer and Sophie Collyer, two highly respected Columbia University poverty researchers, work up estimates as to the effects, and they are striking:

Source: Wimer, C. and Collyer, S., “Expanding the Child Tax Credit Would Cut Child Poverty in Half,”

Columbia University Center on Poverty & Social Policy, October 2017.

The report announcing these findings is only a page long, though, so I emailed the authors for some extra details. Essentially, they explained that they took a 2016 survey from the Census that includes data on income and benefits, located the households that would be eligible for the expanded credit, added the new money to these households’ incomes, and re-calculated the various poverty rates. These estimates were made using the Supplemental Poverty Measure, which addresses a number of serious problems with the Official Poverty Measure, such as that the latter doesn’t count non-cash government benefits as income.

But there are some limitations to their analysis. For one, government benefits tend to be underreported in surveys like the one it relies upon. If these benefits were reported correctly, the current poverty rate would be modestly lower, and the deep-poverty rate significantly so, judging by estimates (based on 2012 data) from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. “Extreme poverty” might hardly exist at all once underreporting is taken into account, per Scott Winship’s report last year for the Manhattan Institute (which I summarized in this space). “Overall, underreporting might affect the pre-reform poverty rate estimate we report but would probably not have a substantial impact on the percent reduction in poverty we find after the reform,” Collyer and Wimer told me.

Second, and more important, the estimates don’t speak to the longer-term consequences of the policy. A $350 monthly check until a child turns six, and $300 monthly checks thereafter, could conceivably increase childbearing among the unmarried and married alike, and could also prod parents to reduce their work effort, both of which could affect poverty rates. “On the childbearing front, our read of the literature is that these effects are minimal to nonexistent,” Collyer and Wimer responded (citing this study from Germany and this one from the U.S.), though they described the literature on work-force participation as “not settled.”

In a fact sheet, the bill’s sponsors dismiss a number of potential unintended consequences, to their credit pointing to research and data to underscore each point. In their narrative, giving parents more money won’t cause them to work less; heck, it will help mothers work more by helping them pay for child care—and on top of that it might reduce the amount of money parents spend on alcohol and tobacco.

But the evidence on these points is messy and uncertain enough that policymakers should tread carefully, starting with smaller changes to the Child Tax Credit and guarding against possible backfires. The consequences of getting this wrong could be enormous if there’s anything at all to the conservative argument that government checks often subsidize and enable counterproductive behavior. Certainly, the explosion of welfare spending starting in the 1960s coincided with a dramatic rise in nonmarital childbearing, for example, even if we cannot scientifically prove that one caused the other.

Republican senators Mike Lee and Marco Rubio provide one alternative. They are pushing the GOP to boost the credit to at least $2,000. And rather than make the credit fully refundable, they would make the credit refundable against payroll taxes, including employer-side payroll taxes, in addition to income taxes. Since payroll taxes amount to 15.3% of income, someone making about $13,000 could take advantage of the full credit for one child, while someone who didn’t work could not receive it. This would subsidize work, in other words, rather than potentially substituting for it, at least among the lowest-earning parents.

There are other options as well for protecting against bad incentives from an increased and fully refundable Child Tax Credit. In the past, I have suggested cutting back welfare programs, such as food stamps, that give more benefits to people with more children. Not only would combining cuts to these programs with a refundable CTC replace a paternalistic in-kind benefit with cash, but unlike most safety-net programs, the CTC doesn’t phase out until workers are well into the middle class. (Earlier phase-outs effectively punish the poor for improving themselves: Get a better job, work more hours, or earn a raise, and you lose your benefits.)

A related alternative, especially attractive to those precious few of us who care about budget deficits, is to pay for an expanded credit by consolidating existing benefits that already go to families with children—the credit being a fairer, flatter, and more flexible way to distribute this money. Last year, Samuel Hammond and Robert Orr of the Niskanen Center pointed out that if you eliminated the dependent exemption, child food-stamp receipts, school nutrition programs, and the dependent-care credit, you could roughly fund a $2,000, fully refundable CTC.

The Bennet-Brown bill has essentially no chance of passing in a GOP-dominated Congress, so for the time being, its main purpose is to make Republicans think. One point comes through loud and clear: If the GOP is willing to increase the deficit by more than a trillion dollars over 10 years, as the party’s budget resolution implies, it wouldn’t be hard to give a lot of money to working- and middle-class families rather than funding tax cuts for corporations and high earners. But another intended message—that a huge, unconditional cash transfer to parents, piled on top of the entire existing welfare state, is the reform our family policy needs—is unlikely to convince.

Robert VerBruggen is a deputy managing editor of National Review.

Editor's Note: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or views of the Institute for Family Studies.