Highlights

- Higher-income households are more likely to rely on non-parental care, while working-class families are just as likely as not to take part in any non-parental care. Post This

- A massive child care push would put a federal thumb on the scale in favor of families with two earners over those that choose to have a parent at home. Post This

The $1,400-per-person checks and one-year introduction of a child allowance got all the headlines in coverage of the recently-passed American Rescue Plan (ARP). But the lines may have been drawn for future battles in some provisions that went under the radar.

The ARP is boosting funding for child care by previously-unknown amounts: $24 billion will go towards new “stabilization grant,” aimed at helping child care centers pushed to the brink by the pandemic. (This comes on top of $3.5 billion allocated towards child care providers in the original CARES Act, and another $10 billion in December’s previous COVID relief bill.) In addition, states will receive an additional $14.9 billion in the Child Care and Development Block Grant, which funds child care services for low-income families, and $3.5 billion for general state child care assistance.

In the tax code, the ARP will also make the Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit much more generous, allowing families to claim up to $8,000 in expenses for one child (up from $3,000), deducted from their taxes at up to 50% (up from 35% previously).

Make no mistake—this was a back-up-the-Brinks-truck approach to policymaking, without much emphasis on reform. To be fair, the child care industry got hit relatively hard during the pandemic, and some of the additional money, similar to those directed at restaurants and the entertainment industry, may have been necessary and appropriate.

But conservatives should be alert to the seeds being planted for something larger down the road. On the campaign trail, then-candidate Biden proposed universal pre-kindergarten for three- and four-year-olds with a price tag of $775 billion. Democrats will get a second bite at the budget reconciliation apple later this summer, and some reports suggest that large-scale provision of child care may be included in a mammoth infrastructure package.

At first blush, including child care in an infrastructure bill seems like a category error—building bridges, airports, and train stations are examples of large capital expenditures that can pay dividends over their decades of use. Setting up large-scale national child care, on the other hand, would entail an ongoing outlay that would likely increase over time.

For their part, child care advocates argue a large-scale approach would be worth it, and may even pay for itself. Some envy the labor force participation of moms in countries with universal child care, and tally up the lost GDP from moms who choose to stay home with their kids rather than enter the labor force.

But conservatives should resist the push for a federal child care program on grounds other than just the large price tag. Primarily, a massive child care push would put a federal thumb on the scale in favor of families with two earners over those that choose to have a parent at home.

New data from a nationally representative study illustrates how families differ in their need for child care. The latest round of the Early Childhood Participation Survey, a subset of the National Household Education Survey, recently came available (it was fielded in 2019, so all numbers are pre-pandemic.)

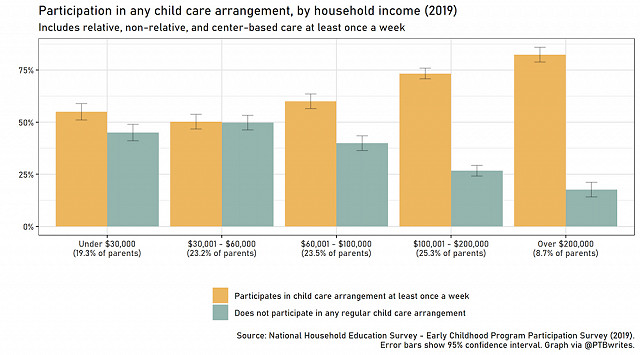

Its findings are intuitive—higher-income households are more likely to rely on non-parental care, such as relatives, child care centers, daycares, or other arrangements, while working-class families are just as likely as not to take part in any non-parental care (the lowest-income parents are slightly more likely to have a child care arrangement reflecting their higher rate of single parenthood.)

Some of this is a mechanical relationship—having two earners in the household automatically raises your total income, so families making less than $60,000 tend not to have multiple parents in the labor force. But it also reflects some rational tradeoffs—after child care expenses and taxes, a working-class family may end up only slightly better off monetarily with both parents working as opposed to one. And income, after all, is only one dimension of family life. In public opinion surveys, a majority of mothers say their ideal work-life situation would be to work part-time or not all.

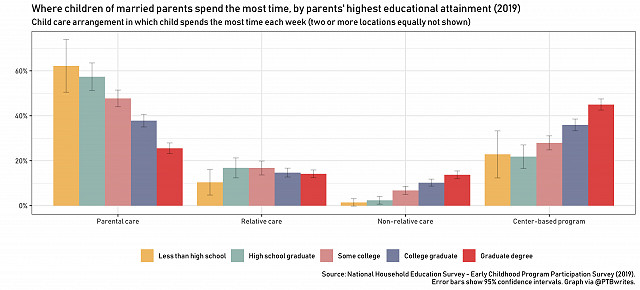

Single parents naturally have a greater need for child care, but even in looking only at married-couple families, the same relationship between earnings potential and child care presents itself. Married families with advanced levels of education are more likely to rely on center-based child care, while families with parents who don’t have a degree tend to keep their kids at home.

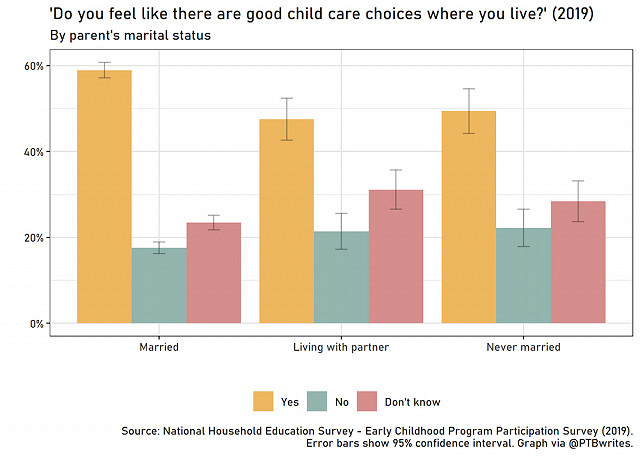

Like student loan forgiveness, a national child care push would be a regressive and heavy-handed way of catering to households with high incomes and advanced levels of education. Yes, some working-class parents would like to work instead of staying home with their children. But a recent YouGov/American Compass poll was the latest to suggest that just as many parents would appreciate a financial benefit that gave them the flexibility to choose the situation that best suited their families’ needs. Indeed, the ECPP itself asks families whether they feel like there are good child care choices near them, and only one-fifth of respondents replied “no.”

This is not to downplay the need for improvements in the child care market. Child care costs are a burden to many families (though not rising as fast as is so often breathlessly reported), with some attributing our nation’s stagnating fertility rate to concerns about cost. A report I authored for Congress’ Joint Economic Committee earlier this year suggested eliminating the Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit in favor of a boosted child credit for young children. Sen. Romney’s proposed Family Security Act also suggested a similar move.

Revisiting the regulations that have accumulated in the Child Care Development Block Grant, and more creative moves to boost supply, including by lifting regulatory barriers, should also be considered. Targeted injections, like the ARP’s stabilization funding, may be a bridge to an eagerly awaited post-pandemic world. But they are unlikely to be the final word.

The push for universal child care will continue, and conservatives who are not prepared for the discussion could get caught on the wrong foot. Debate will continue on whether the $3,000-per-child allowance was a step in the right or wrong direction. But no-strings-attached checks are the lightest-touch form of government intervention. They would pale in comparison to a large-scale effort to guarantee federally-funded child care slots around the country, resulting in a massive expansion in the federal government’s role and establish an implicit cultural expectation that families should have all parents in the workforce.

There is still time for conservatives to avoid being steamrolled by a massive expansion of child care this summer, but they must be ready with alternatives that recognize the diversity of American families’ needs. Plans like the JEC report or Sen. Romney’s Family Stability Act should spur more creative ways to improve the choice set for families and avoid both the progressive one-size-fits all mentality as well as the trap of reflexive opposition.

Patrick T. Brown (@PTBwrites) is a former senior policy advisor to Congress’ Joint Economic Committee and a policy fellow at the Institute for Family Studies.

*Photo credit: Erika Fletcher via Unsplash