Highlights

- If the American political system were to decide on dramatically increased welfare-state spending, the “Family Fun Pack” would be a much stronger blueprint than other proposals. Post This

- Our desired end destination may differ, but family-policy fellow travelers can salute the “Family Fun Pack’s” bold and coherent contrast to pallid centrism and the inadequate status quo. Post This

Centrist pastels are out. Bold, ideological colors are hot right now, and none hotter than the ideas documents being issued from potential candidates and think tanks in advance of what is sure to be a raucous Democratic primary.

Matt Bruenig, the founder of the crowd-funded People’s Policy Project, is influential among young, intellectual leftists, helping to popularize ideas like a sovereign wealth fund, Medicare for All, and a democratic socialist agenda. His latest contribution to the swirl of bold ideas on display is a dramatic re-envisioning of what federal policy could offer American families.

The “Family Fun Pack” deserves to be evaluated on its own merits without recourse to the easy, but insufficient, “how could we ever pay for all this” rejoinder. If the American political system were to decide on dramatically increased welfare-state spending, the “Fun Pack” would be a much stronger blueprint than other proposals to remake the American economy.

On policy grounds, much of the “Fun Pack’s” seven proposals merit some praise. Separating out the work-supporting component of the EITC from the family-related support, and condensing that with other child benefits (the Child Tax Credit, the Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit, etc.) into a flat $300-per-month benefit would be a more equitable way of supporting parents. Guaranteeing a spot for every child in a federally-funded, locally-run child care center, while a massive overreach, is smartly paired in the “Family Fun Pack” with a payment of equivalent value to parents who choose to stay home. The suggested “baby box” for expectant mothers should be a bipartisan deal by tomorrow. The reasonable design of Bruenig’s paid-leave plan also has much to recommend it.

These proposals would expand the choice set for young parents, allowing them to have more resources while also allowing them to more easily structure their family life in the way they best see fit. Bruenig also makes an interesting theoretical point, identifying the potential mismatch between income and child-related expenses over the lifecycle—young parents, who have had less time to establish themselves in the workplace or benefit from seniority, have lower wages, while older workers, who perhaps once were cash-strapped young parents, now bring home higher pay with fewer family expenses. He points out that child poverty rates fall as children age, and rightly pushes back against the too-facile advice to delay childbearing until later in life on both philosophical and practical grounds.

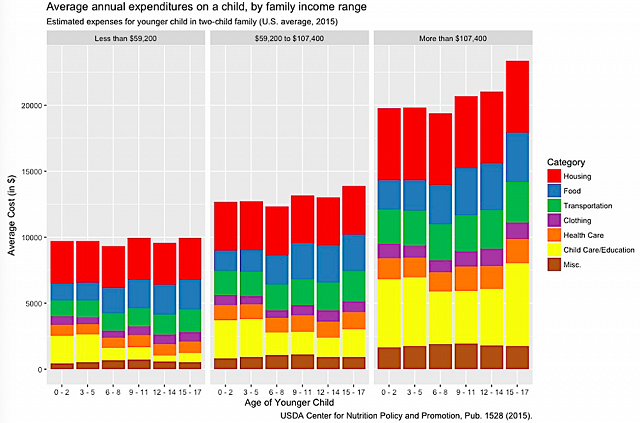

Yet Bruenig’s critiques often overreach. For example, the compelling “lifecycle” concerns may not be as fatal to a capitalist system as he suggests. If one takes the USDA’s estimated cost of having a child at face value (which I don’t, necessarily, but will do so for the sake of argument), child-related expenditures do not—in fact—fall with the age of a child:

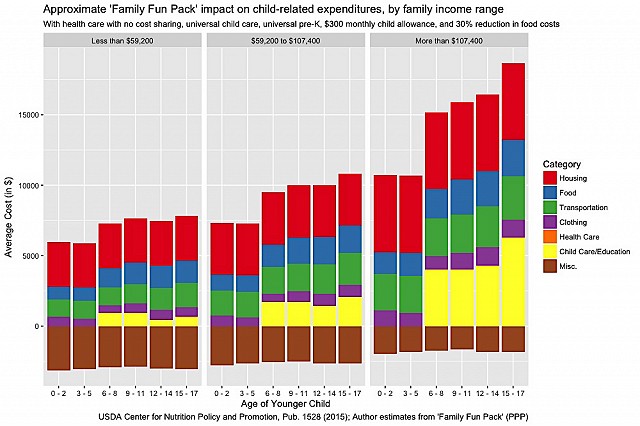

Expenditures, obviously, don’t capture what parents want to be spending, but if we treat wealthy parents’ spending as being relatively unconstrained, the case that child-related expenditures are highest in the early years is unproven. We can compare current spending to a back-of-the-envelope glance at Bruenig’s plan, fully implemented (as I’ve sketched out below). It would eliminate the orange health care spending and the yellow child care spending in early years and reduce the blue food expenditures by roughly a third, topped off with the $300-per-month allowance (note that the brown “miscellaneous” category dips below zero on the y-axis, reflecting the flexible child allowance).

This would undoubtedly subsidize the cost of having a child! But even with this favorable lens, we know nothing about the tax base necessary to support this kind of spending, and this kind of mechanical calculation ignores how people may change their behavior in response to new incentives (the same mistake Bruenig makes when calculating what adult poverty would be without poor children.) Universal programs, while presumably thought to be more politically palatable, would leave well-off parents with even more resources to spend on opportunity-hoarding endeavors, particularly as children get older. If we care about opportunity and economic mobility, the relative disadvantage poor children face in school quality and enrichment programs may get worse.

Specific financial support for families, such as a child allowance, is a better investment than massive social programs that homogenize and standardize all child-rearing according to administrative “best practices” (Bruenig, to his credit, does not offer the same pie-in-the-sky promise as Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.), who suggests that every daycare in the country could be made “high quality.”)

If we think the cost of having children in our society is too high, investing in non-scalable services like universal child care and pre-K runs the risk of inviting unsustainable price tags due to Baumol’s cost disease, where salaries continue to grow despite a cap on how productive any individual worker can be. A more long-term oriented vision for reducing the relative cost of childbearing would be making housing (the biggest expenditure in the USDA’s calculations) more affordable by increasing supply, reducing restrictive regulations on new child care products and services, making it more doable for parents to leave and re-enter the labor force, and allowing competition in the early childhood and education space to drive value for parents.

An expansion of federal power this broad would radically transform the state’s role into provider rather than preserver, and remake the relationship between families and the state.

A few other wrinkles in the “Family Fun Pack” strike me as odd, but I’ll mention one that especially jars: A proposal for universal pre-K goes out of its way to exclude equivalent payments to parents who homeschool, which seems weirdly at odds with the benefit for at-home parents of younger children.

We could stand to reflect more on our ability to restructure our economic system to better fit the modern costs of childbearing. But we cannot ignore the feedback effect on families that greater state intervention might have on interpersonal relationships and social ecosystems. An expansion of federal power this broad would radically transform the state’s role into provider rather than preserver, and remake the relationship between families and the state.

Even the most generous of European nations still face declining fertility, despite higher social spending on family policy. Bruenig’s goal of making having children “easy and affordable for all” likely can’t be met solely through new government entitlements but would be better achieved through targeted interventions and cultural shifts. Reforming corporate practices to prioritize parents re-entering the labor force after a lengthy break, for example, could make it less scary for would-be parents to take time away.

Flaws aside, substantive family policy from the viewpoint of the new left allows everyone’s Overton window to shift, and directing some of that movement’s energy from “green dreams” to meaningfully supporting families is highly commendable. Our desired end destination may differ, but family-policy fellow travelers can salute the “Family Fun Pack’s” bold and coherent contrast to pallid centrism and the inadequate status quo.

Patrick T. Brown (@PTBwrites) is a graduate student at Princeton University’s Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs.

Editor’s Note: The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or views of the Institute for Family Studies.