Highlights

- Mobility for children who were raised in lower-income families is higher for kids raised in neighborhoods with lots of two-parent families, and lower for kids raised in neighborhoods with more single-parent families. Post This

- Communities with more single-parents are much more likely to have boys who end up being incarcerated as adults. Post This

The American Dream is in relatively good shape in some communities—like Seattle and Salt Lake—but in comparatively bad shape in other communities—like Atlanta and Baltimore. This means poor kids raised in cities like Seattle and Salt Lake City have a much better chance of moving up in the world, income-wise, than children raised in Atlanta and Baltimore.

This much is clear in the research of Harvard University’s Raj Chetty, who has succeeded in casting a spotlight on the role that geography plays in sustaining or strangling the American Dream in one blockbuster study after another. Chetty’s research, of course, raises a fundamental question: what factors explain why some communities succeed and others fail in generating economic opportunity for poor children in America?

Headlines in prominent media outlets like The New York Times, The Washington Post, and The Atlantic have fingered factors like “racism,” “poverty,” and “segregation” in explaining why some communities do well and others do poorly in promoting the future economic well-being of the low-income children in their midst. And indeed these factors are key, judging by the work of Chetty and his colleagues.

But these factors don’t tell the whole story, as David Leonhardt at The New York Times recently noted. In discussing Chetty’s newest study, which drills down to explore the effects that individual neighborhoods have on the odds that poor kids make it as adults, Leonhardt listed socioeconomic factors like the ones listed above and then asked his readers to guess which factor he had left off the list. He then went on to write this:

I’ve left off one major item from this list, and I’m curious to see whether you noticed. In fact, I left off the second largest correlation... It is: a neighborhood’s share of single-parent households. All else being equal—income, race, educational outcomes—children who grow up in neighborhoods with fewer two-parent families fare notably worse.

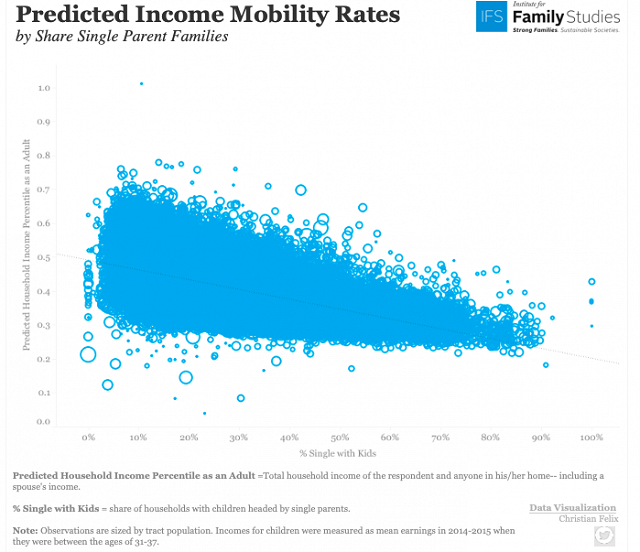

What exactly does the relationship between family structure at the neighborhood level and poor children’s odds of realizing the American Dream look like? By merging economic mobility data from Chetty’s project and Census data on family structure at the neighborhood tract level, here’s what we see:

Indeed, Figure 1 indicates that mobility for children who were raised in lower-income families is higher for the kids raised in neighborhoods with lots of two-parent families, and lower for the kids raised in neighborhoods with more single-parent families. Specifically, boys and girls raised in families with a household income in the 25th percentile were much more likely to escape poverty as adults when they were raised in communities replete with two-parent families.

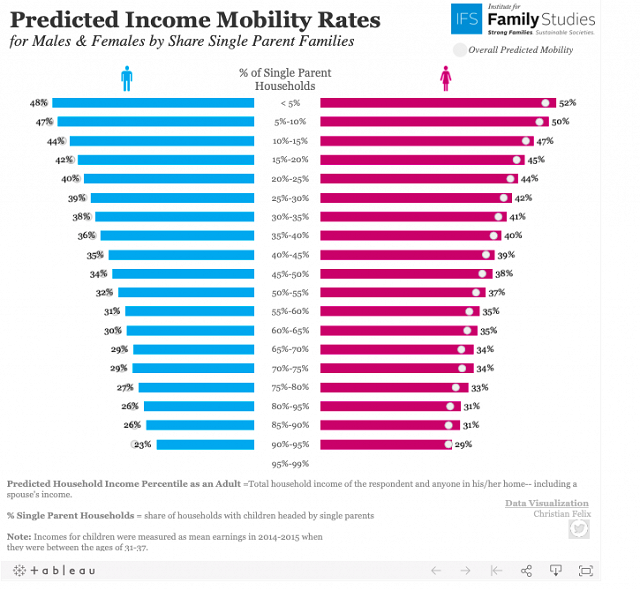

In fact, as Figure 2 indicates, lower-income boys raised in communities where more than 80% of the parents are single parents usually remain stuck at about the 25th percentile when it comes to their household income as adults, while their female peers generally end up not much better—at about the 31st percentile. In other words, neighborhoods dominated by single parenthood tend to lock in intergenerational poverty.

By contrast, Figure 2 shows that poor boys who grow up in neighborhoods where about 80% of the families are headed by two parents are more likely to land in the 40th percentile in household income as adults, and poor girls in such neighborhoods typically land at the 44th percentile in household income as adults. Clearly, economic mobility is higher for poor kids who grow up in a neighborhood with lots of two-parent families.

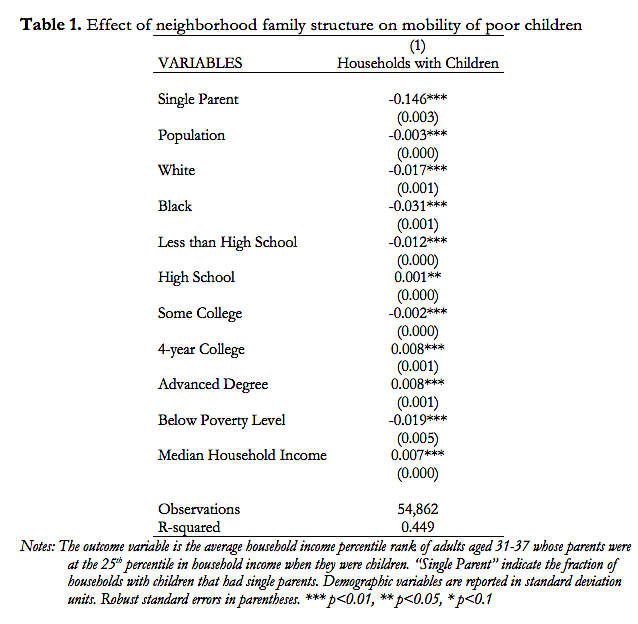

But Leonhardt’s intervention and Chetty’s study also left us curious. What is the link between family structure at the neighborhood level and children’s economic mobility after you control for socioeconomic factors like parental education, race, and poverty in the neighborhood—something that Chetty and his colleagues at Brown and Harvard did not do in their latest study? In other words, is the unique association between family structure robust even after considering these socioeconomic factors? It turns out the answer is yes.

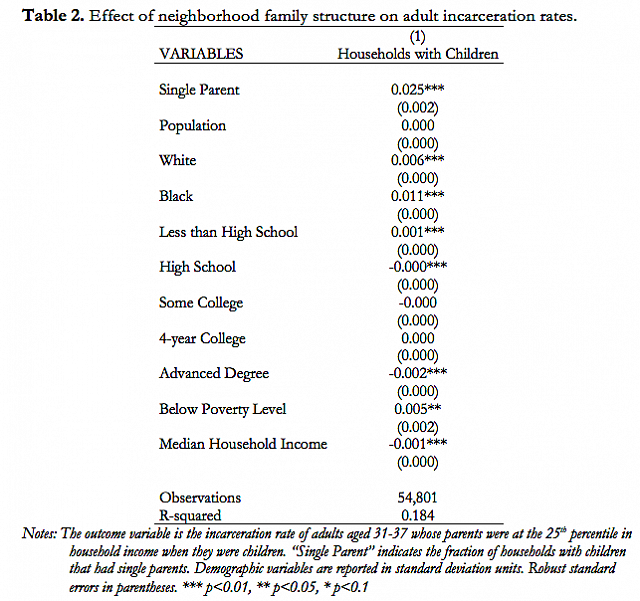

Table 1 indicates that the share of single parents in a neighborhood is statistically significant and the best predictor of mobility for poor children in a neighborhood—at least in comparison to other standard predictors of mobility—when we look at all households with children in a given community. The bottom line here: the family structure that defines and dominates the village is powerfully predictive of economic mobility for poor children in America, even after controlling for other socioeconomic factors that might confound that relationship.

But why does a neighborhood’s family structure matter? Why exactly are villages with more two-parent families better off? Family structure at the neighborhood level matters, in part, because children growing up in communities with more two-parent families are more likely to be surrounded by families who are invested in their child’s schooling, families with a father who is present and working (which has obvious financial benefits and sends the right message to teenagers, especially boys, growing up in the community), and families where fathers help to establish a climate of order and discipline in the home that makes the neighborhood safer. It’s no accident, for instance, that Harvard sociologist Robert Sampson has observed that “Family structure is one of the strongest, if not the strongest, predictors of… urban violence across cities in the United States.”

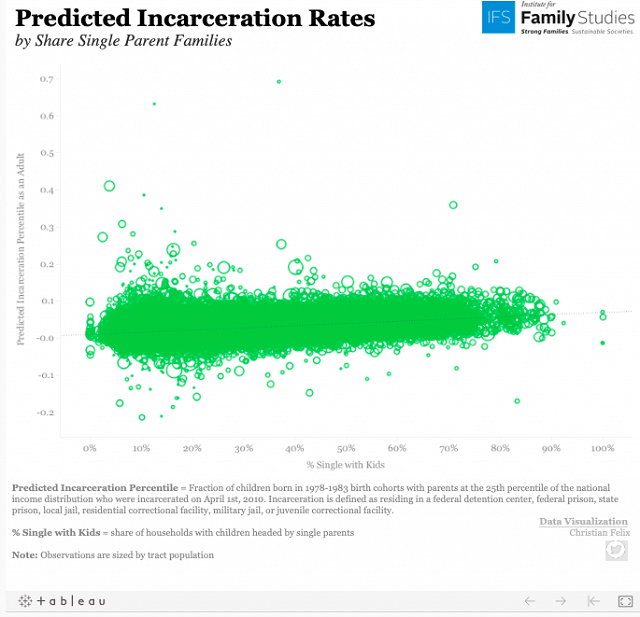

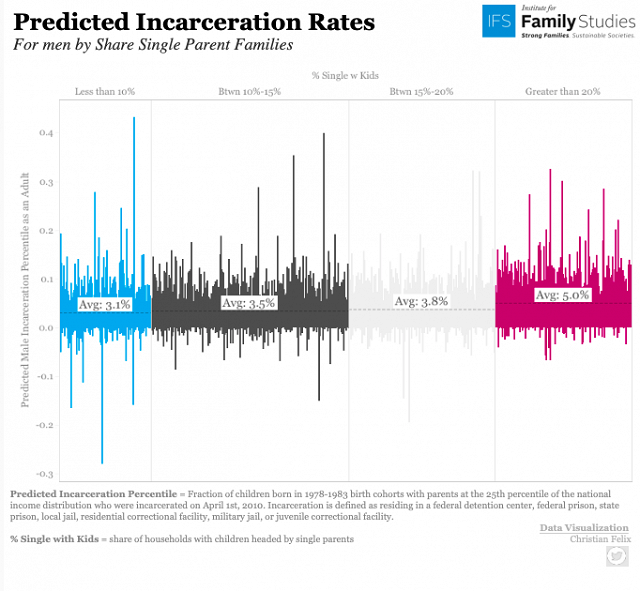

Indeed, as Figure 3 illustrates, we find that there is a strong link between adult incarceration and neighborhood family structure. Communities with more single-parents are much more likely to have boys who end up being incarcerated as adults in their late twenties or early thirties. For instance, in their newest study, Chetty and his colleagues drew attention to the fact that black men growing up poor in two different neighborhoods in Los Angeles had dramatically different odds of being incarcerated as adults:

For example, 44% of black men who grew up in the lowest-income families in Watts, a neighborhood in central Los Angeles, are incarcerated on a single day (April 1, 2010 – the day of the 2010 Census). By contrast, 6.2% of black men who grow up in families with similar incomes in central Compton, 2.3 miles south of Watts, are incarcerated on a single day.

There are a number of factors separating these two neighborhoods, but it’s fascinating to note that single-parenthood was much higher in Watts than it was in Compton when these men were growing up: to be precise, the share of single parents for Watts was 87%, whereas the share of single parents for Compton was 50% in the 1980s, when these men were children.

Figure 4 provides another, more general look at the trends here for lower-income men in their late twenties and early thirties across the United States. It shows that poor boys born between 1978 and 1983 growing up in neighborhoods with more than 90% of the families headed by two parents had only a 3% risk of being imprisoned in 2010. By contrast, poor boys living in neighborhoods where more than 20% of the parents were single parents had a 5% risk of being in prison or jail in 2010—by the time they reached their late twenties or early thirties.

Moreover, in a multivariate context, one of the strongest neighborhood predictors of incarceration for young men from lower-income families is family structure. Table 2 indicates the share of single parents in a neighborhood, it turns out, is a bigger predictor of incarceration in adulthood than race, education, and poverty in a neighborhood. Here, then, we have yet more evidence that family structure at the community level is strongly linked not only to economic mobility but also to incarceration. Indeed, this suggests that one mechanism that explains why family structure matters for the economic mobility of boys is that it influences the odds that they run afoul of the criminal justice system.

These findings on economic mobility and incarceration are especially striking because the role that family structure plays is often downplayed in media and academic coverage of poverty, economic mobility, and even incarceration. This is a point that Leonhardt made in discussing the importance of family structure in Chetty’s newest study:

I want to highlight this result because I think that my half of the political spectrum — the left half — too often dismisses the importance of family structure. Partly out of a worthy desire to celebrate the heroism of single parents, progressives too often downplay family structure. Social science is usually messy, with correlation and causation difficult to separate. But the evidence, when viewed objectively, points strongly to the value of two-parent households (and, no, the parents don’t need to be heterosexual).

In other words, judging by Raj Chetty’s latest study, and our new analysis of the ecological data related to it, it looks like a neighborhood dominated by two-parent families gives poor children a better shot at realizing the American Dream.

W. Bradford Wilcox is Professor of Sociology at the University of Virginia, a Senior Fellow of the Institute for Family Studies, and a Visiting Scholar at the American Enterprise Institute. Joseph Price is Professor of Economics at Brigham Young University. Jacob Van Leeuwen is a researcher in the Economics Department at Brigham Young University. Note: Christian Felix created the figures for this article.

*Photo credit: Wikipedia Commons (original link here)