Highlights

- Individuals who engage in home-centered religious practices are significantly more likely to report high levels of life meaning and happiness in their lives. Post This

- A new study finds that the greatest benefits of religion are experienced by those who actively engage in home-centered religious practices, such as family prayer and reading scriptures, in addition to regularly attending religious services. Post This

- Women and men across the globe who live the Home Worshiper lifestyle are significantly more likely to report having a highly satisfying and stable marriage than less religious or nonreligious individuals. Post This

Many recent studies show that religion has a profoundly positive impact on people’s lives around the globe. In particular, these studies compare highly religious individuals with their less religious or nonreligious peers, and find a consistent and significant beneficial association between religiosity and a variety of measures of individual and family well-being.

However, it is possible that many current studies are underestimating the full benefits available from religious participation because they do not distinguish between individuals who are receiving a “full dose” of religion and those receiving lower dosage levels. Most notably, it is standard practice in many research studies to distinguish religiosity levels by the frequency with which the respondents attend religious services—with those who never attend services being identified as “secular” or “nonreligious,” those who attend occasionally being identified as “nominal” or “less-religious,” and those who attend regularly as “active” or “highly religious.” Often weekly or more attendance at religious services is used as an identifier for high religiosity, but some studies are starting to identify highly religious individuals as those who simply attend religious services at least once per month.

But is this how highly religious individuals would identify themselves? In addition to regular attendance at religious services, all world religions encourage their followers to bring religious observance into their daily lives through home-centered religious practices and personal forms of worship. Most notably, nearly all faith traditions teach the importance of communing with the Divine through engaging in personal prayer and contemplation, reading scriptures or holy writ, discussing religious teachings in one’s home, and gathering one’s family together for shared family prayers, worship, and devotion.

When home-centered religious practices are taken into account, it appears that current practices of measuring religiosity are at risk of underestimating the full effects of religion on followers. This is because these studies do not distinguish those who engage in home-centered religious practices in addition to regular church attendance, from those who attend church regularly, but do not actively engage in these practices at home. Indeed, current methods that rely solely on church attendance to distinguish “religious dosage” may be adequate in identifying nonreligious and nominally religious individuals, but they do not satisfactorily distinguish the truly highly religious in most faith communities.

Could it be that home-centered religious patterns help contribute to benefits for individuals and couples above and beyond attendance at religious services alone? We recently released a new report to examine this question.

Our new report, A Not-So-Good Faith Estimate: Why Many Studies Underestimate the Full Benefits of Religion, drew from the 2018 Global Faith and Families Survey (GFFS2018), which sampled adults between the ages of 18 and 50 over a two-week period.1 The survey included over 16,000 individuals from 11 countries, including Argentina, Australia, Canada, Chile, Colombia, France, Ireland, Mexico, Peru, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

In our study, we explored how regular engagement in home-centered religious practices influences individual well-being and relationship outcomes beyond church attendance alone. In particular, we examined the effects of “religious dosage” across four groups:

- Seculars – Non-religious individuals who never attend church and report that they never engage in personal worship practices (31% of the U.S. sample and 31% of the international sample).

- Nominals – Individuals who report some amount of either personal or public religious participation, but do not regularly attend religious services (43% of the U.S. sample and 49% of the international sample).

- Attenders – Individuals who attend church weekly and engage in some home worship patterns, but do not do so regularly (15% of the U.S. sample and 13% of the international sample).

- Home Worshippers – Individuals who attend church at least weekly but also pray daily and engage in the home worship practices of praying together as a family, reading scriptures, and having religious conversations in the home at least two to three times a week (11% of the U.S. sample and 8% of the international sample).

Religious Dosage Matters

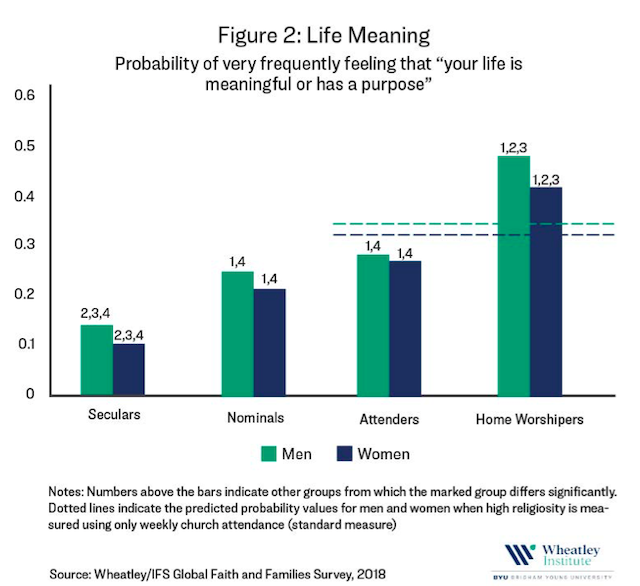

On several measures of individual well-being and relationship quality, we found that religious dosage matters. The full benefits of religion are experienced by those who actively engage in home-centered religious practices, in addition to regularly attending religious services. For example, individuals who engage in home-centered religious practices are significantly more likely to report high levels of life meaning and happiness in their lives. Specifically, “Home Worshipers” are nearly twice as likely as their less-religious peers, and more than four times more likely than Seculars to report a frequent sense of meaning and purpose in their lives.

We also found an increase in reported life happiness with each dosage category of religious involvement. Home Worshipers are significantly more likely to report high levels of happiness than are Attenders, Nominals, or Seculars. In the U.S., we found a similar pattern, with Home Worshiper men and women reporting the highest levels of life happiness. However, in contrast to the international sample, the U.S. pattern is more notable for women than for men. In terms of magnitude, Home Worshiper women in the U.S. are about twice as likely as Attender women and four times as likely as Secular women to report a high level of life happiness.

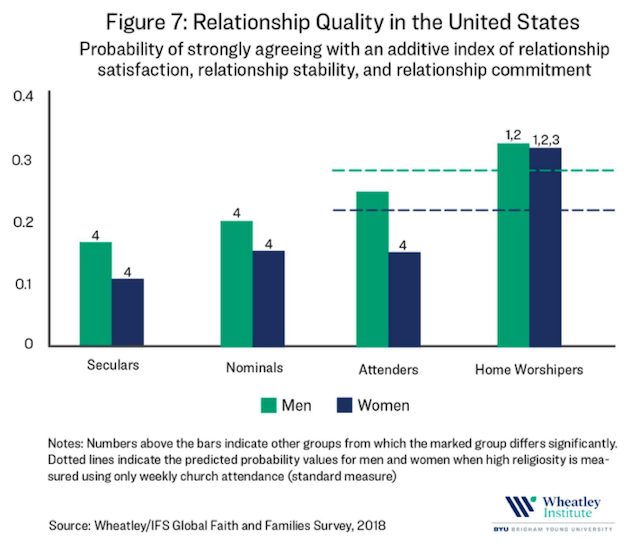

Our study also found that women and men across the globe who live the Home Worshiper lifestyle are significantly more likely to report having a highly satisfying and stable marriage relationship than less religious or nonreligious individuals. In the U.S., Home Worshiper women and men also have the greatest likelihood of reporting that they are in a high-quality marriage relationship. Specifically, U.S. men in Home Worshiper relationships are roughly twice as likely to report that they are in a high-quality marriage than their Secular peers, whereas Home Worshiper women are three times more likely than their secular peers and two times more likely than their Attender peers to report a high quality marriage.

Moreover, individuals who engage in regular patterns of home worship also report significantly higher emotional closeness and sexual satisfaction in their marriages than individuals who only attend church regularly or don’t attend church at all. In a previous report, we found that couples who regularly engage in home religious practices also report significantly higher levels of shared decision making between partners, fewer money problems, and more frequent patterns of loving behavior such as forgiveness, commitment, and kindness.

Many Studies Underestimate the Benefits of Religion

Our study also provides clear evidence of the deficiencies in the often-used practice by many public studies of measuring religiosity solely by levels of church attendance. In fact, combining individuals and families who engage in home-centered religious practices with those who only attend church not only conceals these differences, but also leads to the erroneous conclusion that the potential benefits of religion are smaller than they actually are.

Our findings suggest that measuring religiosity with only church attendance underestimates the benefits of religion by approximately 25%, on average, and can be as high as nearly 50% on certain outcomes. This means that highly religious individuals who engage in home-centered religious practices frequently score 25% higher, and in some cases as much as 50% higher, than is often reported for “highly religious” individuals in many public research studies.

We also found that highly religious women in the U.S. are the sample most underestimated by measuring religiosity with only church attendance levels—with home-worshiping women scoring 40% higher, on average, on measures of personal well-being and relationship quality than standard measures of religiosity would typically show.

Religion, it appears, is one way for people to find meaning and connection. Therefore, it is not surprising that the extent to which one engages in religious practices is predictive of the extent to which one gains the anticipated benefits of religion. Separating those who engage fully in their faith from those who only engage partially makes this conclusion clear. Future research on the influences of religion should consider the drawbacks of measuring religiosity solely using religious attendance or affiliation, as the results will likely underestimate the richer benefits of home-based religious practices.

Jason S. Carroll, Ph.D. is the Associate Director of the Wheatley Institute, a Professor in the School of Family Life at Brigham Young University, and a Senior Fellow of the Institute for Family Studies. Spencer L. James, Ph.D. is an associate professor and Director of the Global Families Research Initiative in the School of Family Life at Brigham Young University. He is also a Fellow of the Wheatley Institute and a Senior Fellow of the Institute for Family Studies.

1. Note: Ipsos Public Affairs, a prominent social research firm, conducted the survey on behalf of the Wheatley Institute and the Institute for Family Studies.