Highlights

In a recent study, Bethany Gull and Claudia Geist identify two paths leading to men's increased housework participation—one nonreligious and egalitarian, the other religious and family-centered. Their results surprised them, as they had expected conservative religious men to have lower housework participation due to their traditional gender ideologies.

We were not surprised by their findings. We suggest there are two basic reasons people assume religious men refrain from household chores: the first is a caricature of religious men as misogynistic, narcissistic, and controlling; the second is that many people understand that egalitarianism places high expectations on husbands and fathers, without recognizing that faith does likewise.

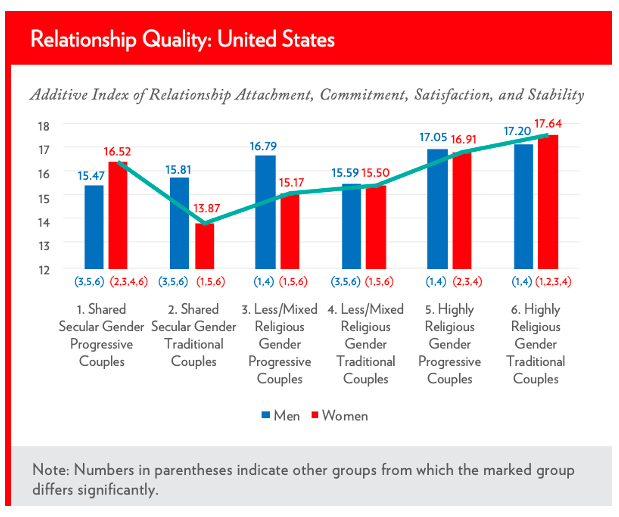

Egalitarianism and faith both seemed to enhance relationship quality in the Global Faith and Gender Survey, the data used in The Ties That Bind: Is Faith a Global Force for Good or Ill in the Family?, a 2019 report from the Institute for Family Studies and the Wheatley Institution. The report found a "J-curve" for women's relationship quality in the United States, as shown in the figure below:

Note that women in egalitarian secular couples at the far left (1) have quite good relationships, as do women in highly religious couples (5,6). The lowest quality relationships obtained among women who benefitted from neither faith nor egalitarianism (2). Women in less religious and mixed religious couples also fell between the two higher ends (3,4).

Gull and Geist's findings regarding housework similarly point to problems in the "mushy middle." They found that men who attended religious services monthly did less housework than men who never attended, plus that both sporadic and occasional attenders were less likely to share in traditional female tasks. But, in keeping with the J-curve, men who attended religious services weekly did significantly more housework than either the never-attenders or those in the middle.

It seems that women are happier when men are involved at home, and that it matters less whether egalitarianism or faith spurs men's involvement.

Previous work has noted that both feminism and faith call for devoted family men, and that both culturally progressive and religiously conservative fathers report high levels of paternal engagement. Nevertheless, being an engaged father by rough-housing with the kids while mom makes dinner and cleans up afterwards is quite different from being an engaged father who also does housework. Gull and Geist are the first to show that religious men do more housework than others.

Think about domestic work as the sum of care work plus housework: previous research shows that religious men provide lots of child care, but most of this research has not addressed whether they dropped the ball on the less relational side of domestic work. The one study paying attention to the difference hinted that religious men were better family men than they were houseworkers. Gull and Geist's data instead affirms that religious men's family-centeredness includes taking care of the house.

We do find it odd that it continues to be surprising to some that religion promotes participation at home. When an opinion piece describing results from The Ties That Bind ran in the New York Times, for example, it was titled "Religious Men Can Be Devoted Dads, Too." But when did this become headline-worthy?

Gull and Geist seem to have uncovered a new pathway to men's participation at home, namely the religious and family-centered one. The commonly recognized non-religious egalitarian path is actually newer. Historically, religion and family-centeredness have gone together, yet the image of the "new dads" is today colored much more by secular egalitarian fathers than by traditionally involved fathers.

There is discourse that claims gendered ideologies inhibit men’s involvement. But most religions are pronatalist and family-oriented. Many religions are also proponents of traditional gender ideologies that view the man’s role as leader, protector, and provider. Given that understanding, it seems safe to assume that many highly religious men have a vested interest in carrying out their role as the family head with involved love and devotion, especially, since faith adds a certain divine calling to each of the roles. It would be surprising if a man called to value his wife above his work would be content to spend his evenings being served by her.

We conclude with a recommendation that is more for the academics in the crowd than those with practical interests in family. Sociologists recognize that people "do gender" in their daily lives, a phrase that refers to behaviors appropriate to socially constructed understandings of gender. As Gull and Geist write: "The extent to which individuals do gender is notoriously difficult to assess, but we include a measure that indicates adherence to traditional ideas about the division of labor between spouses in the labor market."

They are not alone in reducing "doing gender" to the male breadwinner/female homemaker roles. If, instead, scholars recognized that religiously constructed understandings of gender require religious men to “do gender” at home as well as in the marketplace, they might be less surprised that highly religious men are involved at home. That would also explain why men whose lives are not highly scripted by either egalitarianism or religion comprise the trough of the J-curve when it comes to housework.

Laurie DeRose is a senior fellow at the Institute for Family Studies, Assistant Professor of Sociology at the Catholic University of America, and Director of Research for the World Family Map Project. Anna Barren is a graduate of the Philosophy program at Christendom College and is the administrator of the Sociology department at the Catholic University of America.