Highlights

- A fundamental shift in the American safety-net, from one that is tied to work to one that is not, is a matter of utmost public concern in its own right. Post This

- Most Americans think a program of permanent, unconditional cash payments would be a mistake. Post This

- While the “evidence-based” policymaker seizes on the upside of cash, without considering the downside of making it unconditional, the typical American voter seems to approach the issue in a more nuanced manner. Post This

A sure sign that the Child Tax Credit (CTC) should not become a permanent program of unconditional cash payments is that its advocates refuse to say their proposal out loud. President Biden pitches the policy as a “significant tax cut to America’s working families.” The White House webpage dedicated to raising awareness uses the phrase “working families” five times in the first three paragraphs and then features four illustrative infographics, all of working families already above the poverty line.

Now, a group of 448 economists has issued an open letter, urging congressional leaders to make permanent the CTC’s one-year expansion. But the letter makes no mention that these payments would be entirely disconnected from work. Either the economists are unaware of this reality, or, more likely, they’ve chosen to make tendentious claims in its face.

“Expanding the CTC would dramatically reduce childhood poverty,” the letter declares, and “research shows that reducing child poverty improves” all manner of outcomes. But notice the sleight of hand in that two-part formulation. It’s not the CTC’s free-cash approach to poverty reduction that their research supports. In fact, five of the first six studies they cite concern Earned Income Tax Credits (EITC), paid only to working households with the explicit objective of rewarding work. The sixth concerns food stamps, a conventional safety-net program very different from unconditional cash handouts.

When stated plainly, the chain of logic is rather less sophisticated than the economists might hope their citations imply: Children raised in poverty fare worse than children raised in better-off households. Giving households money so that their incomes exceed the poverty threshold will mean that fewer children are in poverty. Therefore, outcomes will improve. QED.

This is a quintessential illustration of the pitfalls of “evidence-based policymaking.” Of course evidence should inform the policymaking process, but sterile translation of arbitrary “natural experiments” and narrow pilots into society-altering programs misses the political-economic forest for the econometric trees. The result is policymaking conducted with three enormous blind spots.

First is the issue of long-term consequences. An unexpected windfall to a family at one moment in time delivers all the benefit of increased resources without the costs associated with changed incentives or social norms. Delivering expected windfalls to every family indefinitely is a very different matter. How will the policy affect family formation and stability, or cultural acceptance of idleness? The economists offer no insight here.

Second is the issue of public understanding. How policymakers define a problem and justify their action guides not only development of the policy’s specifics, but also the public understanding of its function, which together determine how it will operate in practice. A fundamental shift in the American safety-net, from one that is tied to work to one that is not, is a matter of utmost public concern in its own right, and it will only amplify the long-term consequences.

Third is the issue of tradeoffs. Stipulate that if one had a pile of money and only two choices, giving it to low-income families or setting it on fire, then giving it to low-income families would be the better choice. That is all the economists’ “evidence” proves. In the real world, policymakers must consider two other factors. One is where the resources will be taken from and the costs that might have. The other is whether the resources might be better used elsewhere.

It’s quite ironic that the economists rely upon studies showing the EITC’s effectiveness to defend a policy so antithetical to the EITC’s ethos of establishing and rewarding connections to the workforce. Why not just expand the EITC, then? Certainly nothing in their studies suggests that a policy they did not test is better than the one they did.

Contra the economists, consider what the American people say about severing all connection between benefits and work. At American Compass, we conducted an in-depth survey that explained how the unconditional CTC actually functions and then asked registered voters what they thought of it.

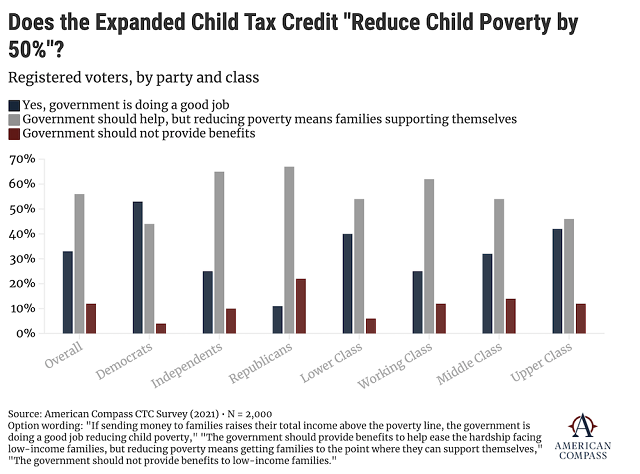

One of the most striking results addresses the concept of reducing poverty at the heart of the economists’ case. The survey explained that President Biden’s claim to “cut child poverty in half” relies on counting the new government benefit as income and asked respondents their reaction. Most rejected this approach and instead sided with the view that “reducing poverty means getting families to the point where they can support themselves.” Working-class voters were least likely to accept the handout model of poverty reduction, and even among Democrats, only 53% were supportive. Independents were nearly as committed to self-sufficiency as Republicans.

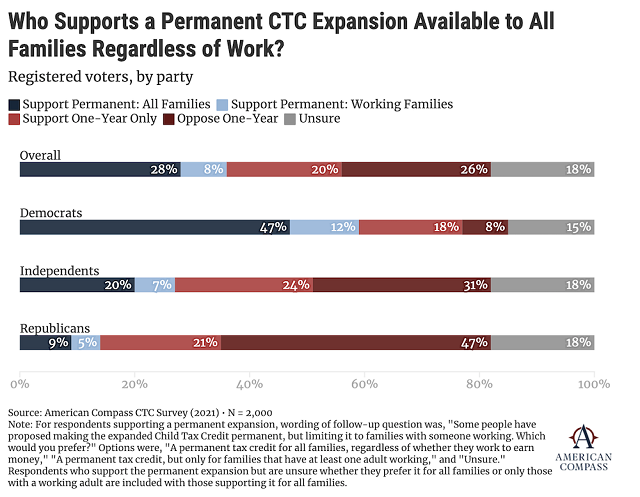

This may help explain why most Americans think a program of permanent, unconditional cash payments would be a mistake. Only 36% support a permanent CTC expansion, and among those, some would prefer it to go only to working families. Only 28% stand with the economists.

Then again, it’s somewhat hard to say where the economists actually stand. Rather than defend forthrightly a claim that work should be irrelevant to a child benefit, the letter mentions only oblique concerns from the right-of-center that the CTC expansion reduces work incentives. But that’s not responsive to the worry that most Americans have. The issue is not whether a single parent works a few hours less every week; what they want to see is a connection to work. In his recent New York Times essay, Patrick T. Brown provides valuable color from recent focus groups:

The parents we talked to felt a tension between the obvious benefits a monthly benefit could bring but still wanting some kind of work requirement. Work made a family deserving of government support; without it, family benefits were seen as welfare. A Hispanic mom in her late 30s ticked off her monthly expenses—food, rent, car—and admitted that an extra $300 to $400 per month would be ‘really beneficial.’ But, she added, ‘it could also coddle people that don’t want to work and are playing the system.’

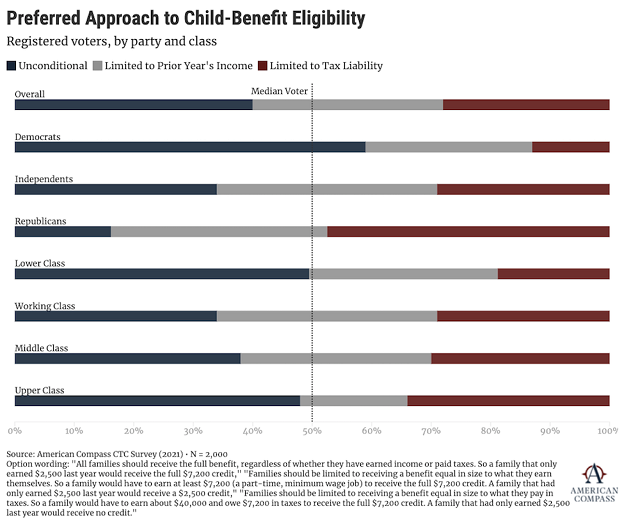

Our survey validates that distinction and presents a clear challenge for the economists. We offered respondents three options for how a child benefit might be calculated: the current expansion’s unconditional formulation; the pre-expansion system in which the credit value cannot exceed the value of taxes owed; or an income-match formula that caps the credit value at a household’s total earnings the prior year, an approach we have proposed. This income-match formula would preserve a connection to work while allowing even the lowest earners to receive the full value—something a taxes-owed approach precludes.

While the unconditional option received 40% support, 60% of Americans preferred some requirement that the family earn income itself: either the income-match (32%) or the status quo ante (28%). This places the median voter squarely in the camp supporting an expanded credit capped at household income. That option was the most popular one with working-class voters and Independents. Even among Republicans, the status quo ante option earned only 47% support, meaning that most preferred something more generous and the median Republican preferred the income-match.

Providing more resources to low-income households is a worthy and broadly shared policy goal. But while the “evidence-based” policymaker seizes on the upside of cash, without considering the downside of making it unconditional, the typical American voter seems to approach the issue in a more nuanced manner. Yes, expand the Child Tax Credit. Yes, ensure that even a household with a single, part-time worker earning the minimum wage can receive the full value. But no, don’t treat work as if it doesn’t matter. The economists have no way to adjudicate this dispute, which is why we need politics to.

Wells King is research director at American Compass. Oren Cass is the executive director of American Compass and author of The Once and Future Worker: A Vision for the Renewal of Work in America (2018).

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or views of the Institute for Family Studies.