Highlights

On February 28, students returned to Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, just two weeks after 17 of their classmates were killed in one of the most devastating mass school shootings in U.S. history. How the students process the violence and heal from the trauma they’ve experienced, especially those who survived and/or witnessed the actual attack, largely depends on the presence of supportive adults in their lives.

Witnessing or experiencing community violence is on the list of “potentially traumatic events” that are classified as Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and range from poverty to having an incarcerated parent, depending on the varied definitions. ACEs have been linked to a multitude of harmful physical, mental, and emotional health outcomes for children and adults, particularly among those with multiple ACEs.

According to a new Child Trends research brief by Vanessa Sacks and David Murphey, nearly half (45%) of children in the United States have experienced at least one ACE, and 21% have experienced two or more. Sacks and Murphey based these findings on data from the 2016 National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH). The survey questions parents about nine common ACEs but does not include child abuse or neglect in the list (which is included in the CDC’s definition). The Child Trends study focused on the following eight NSCH questions, where parents were asked whether a child had ever:

- Lived with a parent or guardian who became divorced or separated

- Lived with a parent or guardian who died

- Lived with a parent or guardian who served time in jail or prison

- Lived with anyone who was mentally depressed or suicidal, or severely depressed for more than a couple of weeks

- Lived with anyone who had a problem with alcohol or drugs

- Witnessed a parent, guardian, or other adult in the household behaving violently toward another (e.g., slapping, hitting, kicking, punching, or beating each other up)

- Been the victim of violence or witnessed any violence in his or her neighborhood

- Experienced economic hardship “somewhat often” or “very often” (i.e., the family found it hard to cover costs of food and housing).

Nationwide, 55% of U.S. children have experienced none of these ACEs, 24% have experienced one, 11% have experienced 2 or more, and 10% have experienced 3 to 8. At the state level, the prevalence of reported ACEs varies. For example, Arkansas has the highest prevalence of children with an ACE at 56%, while three states—Maryland, Massachusetts, and Minnesota—have the lowest prevalence. One in 7 children in five states (Arizona, Arkansas, Montana, New Mexico, and Ohio) have three or more ACEs.

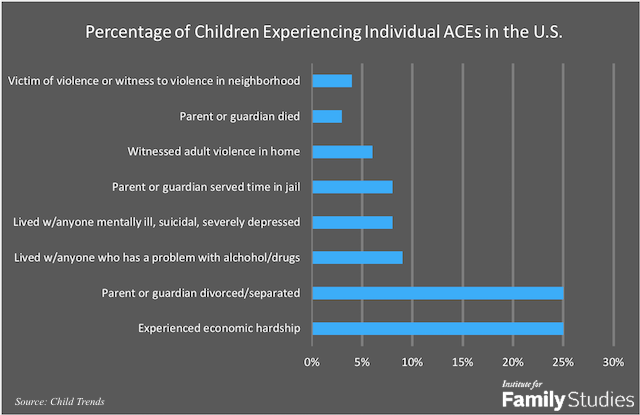

Nationally and in every state, the two most common ACEs reported by parents are economic hardship and divorce/separation of a parent or guardian (see figure below). About one-quarter of children have experienced at least one of these, and this finding holds regardless of a child’s race.

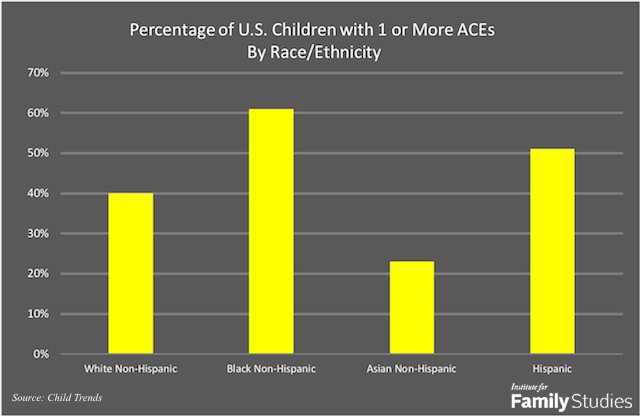

The prevalence of ACEs also varies by race and ethnicity, with “black and Hispanic children and youth in almost all regions of the United States…more likely to experience ACEs than their white and Asian peers.” As the figure below shows, 61% of black non-Hispanic children, 51% of Hispanic children, 40% of White non-Hispanic children, and 23% of Asian non-Hispanic children have one or more ACEs.

Difficulty making and keeping friends, having a hard time calming down, being easily distracted and disengaged at school, and having a higher likelihood of being expelled are among the negative outcomes associated with ACEs in childhood, particularly for those who experience multiple traumatic events. Children with several ACEs are also at a higher risk of physical health problems. A report by the Child & Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative (CAHMI) notes that 33% of children with two or more ACEs suffer a chronic health condition, versus only 13.6% of those with no ACEs. There is also some early research indicating the possible intergenerational transmission of the negative outcomes of ACEs. The Child Trends report points to one recent study that found: "Infants born to women who experienced four or more childhood adversities were two to five times more likely to have poor physical and emotional health outcomes by 18 months of age."

As Sacks and Murphey explain, repeated traumatic events in childhood can lead to toxic stress, which can interfere with the body's natural development, including altering the brain:

ACEs can cause stress reactions in children, including feelings of intense fear, terror, and helplessness. When activated repeatedly or over a prolonged period of time (especially in the absence of protective factors), toxic levels of stress hormones can interrupt normal physical and mental development and can even change the brain’s architecture.

The repercussions of ACEs can follow children into adulthood. The long-term effects, which increase in risk with the number of ACEs, include smoking, alcohol and drug abuse, mental and physical health problems, relationship troubles, suicide, criminal activity, and even early death.

Although experiencing multiple ACEs puts children at a higher risk for these and other harmful outcomes, these children are not doomed to become adults who commit crimes, abuse drugs, or die young. “Adverse experiences do not necessarily lead to toxic levels of stress; here, the buffering role of social support and other protective factors is critical,” Sacks and Murphey emphasize. “The cultivation of supportive, protective conditions by parents, by children themselves, and by their broader communities provides an ambitious but essential public health agenda.”

Stable family routines are one way to protect against the negative effects of ACEs. According to the CAMHI study:

Children whose parents report ‘always’ having positive communication with their child’s health care providers are over 1.5 times more likely to have family routines and habits that can protect against ACEs, such as eating family meals together, reading to children, limiting screen time, and not using tobacco at home.

Additionally, a child’s “own interpersonal skills” and the development of resilience in children and adults (practicing self-care, empathy, and self-regulation) may also provide a defense against the long-term health outcomes of ACEs. The CDC recommends adult mentorship, career workshops and parenting education programs, affordable quality childcare, and after-school activities as ways for communities to help children and families facing ACEs.

But the most powerful protective factor against the harms of ACEs is a supportive relationship with a parent or other trusted adult, which Child Trends notes can buffer against "toxic levels of stress." Here, we can point to J.D. Vance who not only survived but thrived despite a history of multiple ACEs, including parental divorce, drug abuse, and domestic violence. He credits his success to his grandparents and others who invested in his life, including his older sister and aunt, as well as many teachers and friends. “At every level of my life and in every circumstance, I have found family and mentors and lifelong friends who supported and enabled me," Vance writes in Hillbilly Elegy. “Remove any of these people from the equation, and I’m probably screwed.”

Alysse ElHage is editor of the Institute for Family Studies blog. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or views of the Institute for Family Studies.