Highlights

- The marriage-before-children life course sequence can no longer be taken for granted among the college-educated; rather, a substantial minority will have a first child prior to marrying, if they marry at all. Post This

- Some college-educated young adults in the U.S. may be moving toward a pattern we have come to associate with Northern Europe, in which couples have a child outside of marriage, usually while cohabiting, and then marry later. Post This

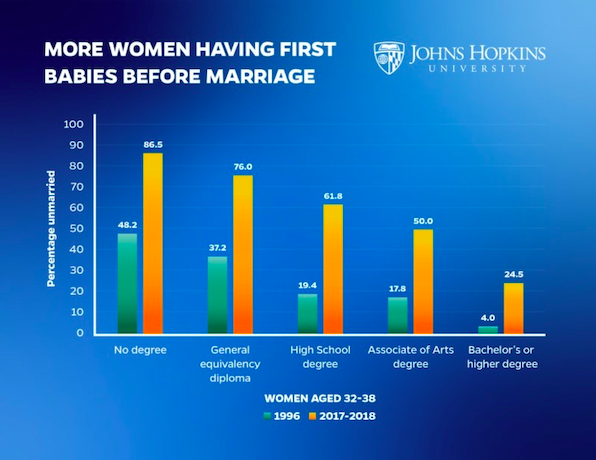

- Back in 1996, only 4% of college-educated women had a first child outside of marriage. By 2017-2018, the percentage of college graduates with a nonmarital birth had increased six-fold (to 24.5%). Post This

Over the past few decades, marriage, while remaining widespread, has become less central to the family lives of young adult Americans. As numerous studies have shown, the percentage who ever marry has declined, cohabitation has increased, and more children are born outside of marriage. But college graduates have been the exception. To be sure, their likelihood of cohabiting has increased, and the age at which they typically marry has risen sharply. Yet the overall decline in marriage has been more modest among college graduates than among the less-educated. Moreover, few of them have had a first child without marrying. But the percentage who have a nonmarital first birth is rising, as I report in an article in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The data also suggest, however, that having a nonmarital first birth does not necessarily indicate a lifelong rejection of marriage. Rather, some college-educated young adults may be moving toward a pattern we have come to associate with Northern Europe, in which couples have a child outside of marriage, usually while cohabiting, and then marry at a later point.

The accompanying figure shows a comparison of reports of nonmarital first childbearing in a 2017-2018 survey compared to reports in 1996 by women in the same age group. It draws upon two different cohort studies by the National Longitudinal Survey of youth. From the 1979 cohort, we can obtain information on women who were aged 32 to 38 in 1996. From the 1997 cohort, we can obtain information on women who were 32 to 38 in the 2017-2018 period. We can therefore do a comparison of nonmarital first childbearing prior to marriage among comparably-aged women 20 to 21 years apart. The figure presents information on all women who had had a first birth, marital or nonmarital, grouped by their educational level.

As the figure clearly illustrates, the percentage of women who had a first birth outside of marriage rose substantially for all educational groups. Among women without high school degrees, nonmarital first childbearing is now ubiquitous. Among high-schools graduates, it is now the majority experience. Even among those with associate of arts degrees, half had their first child outside of marriage.

The percentage of births that are nonmarital is lowest among college graduates. But the proportional increase among them is the largest of any educational group. Back in 1996, only 4% of them had a first child outside of marriage—a figure that was so low as to be ignorable. One could assume that marriage came before having a first child for nearly all college-educated young adults. By 2017-2018, however, the percentage of college graduates with a nonmarital birth had increased six-fold (to 24.5%). It’s no longer a rare event. We need to develop a different perspective on the place of childbearing and marriage among college graduates.

The women who were 32 to 38 in the 2017-2018 survey haven’t finishing their childbearing years. The percentage who will ever have a first nonmarital birth could look different when they are in their late 40s. To calculate a lifetime prevalence of nonmarital first childbearing among college graduates, I supplemented the data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, 1997 cohort, with two other national studies: wave five of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health, better known as Add Health, conducted in 2016–2018; and the pooled 2015–2017 interviews in the National Survey of Family Growth. Using these surveys, along with a few assumptions I describe in my longer article, I estimated that by the time that college-graduate women now in the 30s reach the end of their childbearing years, 18 to 27% of those who have children will have had their first birth outside of marriage. The current data also show that about half of the nonmarital births to college-educated women occur among those who are cohabiting and about half occur to those who are single.

Yet having a first child outside of marriage doesn’t preclude the possibility of marrying at a later time. I examined information in the three studies on college-educated women who experienced a first child outside of marriage and who went on to have a second child. I found that about half of them had married by the time of the second birth. The proportion who had married by the time of the second birth was higher for college graduates than for women without a college degree, one-quarter to one-third of whom had married by the time of the second birth. What is more, in the majority of cases among college-educated women, the father of the second child was also the parent of the first child.

What, then, does this study tell us about the place of marriage in the formation of families? The marriage-before-children life course sequence can no longer be taken for granted among the college-educated; rather, a substantial minority will have a first child prior to marrying, if they marry at all. Some of them will be unpartnered while others will be cohabiting at the time of the nonmarital birth. Nevertheless, it will be common for college-educated women who have a first birth outside of marriage to marry prior to having a second birth, often to the same other parent. This way of forming families is widespread in Northern European countries, such as France and the Nordic nations. For instance, half of all children born to cohabiting parents in Sweden will see their parents marry by the time they are 12 years old.1 Marriage, for these families, becomes something of a capstone event, occurring after the couple has passed several of the markers of partnered life, most notably having children. This way of doing one’s family life course may now become common among highly-educated young adults in the United States.

Andrew Cherlin is Professor Emeritus of Sociology at Johns Hopkins University. His most recent book is Labor’s Love Lost: The Rise and Fall of the Working-Class Family in America.

1. Andersson, Gunnar, Elizabeth Thomson and Aija Duntava. 2017. "Life-Table Representations of Family Dynamics in the 21st Century." Demographic Research 37 (Article 35): 1081-230.