Highlights

- On paper, welfare penalizes both biological parents living with their children, married or not. But in practice, welfare uniquely penalizes marriage and incentivizes cohabitation. Post This

- Using the tax code as a general guide, safety-net eligibility thresholds should be raised for poor and working-class married couples. Post This

Yesterday in this space, I discussed the growing trend of family breakdown in America, the harm that family breakdown causes—especially to children—and the fact that family breakdown is concentrated among America’s poor and working class. I concluded that a significant contributor to family breakdown may be stiff penalties to marriage, embedded in America’s welfare system.

Going forward, although the causes of and solutions to these problems are certainly complex, one simple, low hanging, and obvious change we can make is to reduce large marriage penalties in our safety net. This article provides a reform example using my home state of Minnesota’s childcare benefit, as this is the program with the largest marriage penalty in the state.

The Modern Safety Net Penalizes Marriage

First, we need to understand modern marriage penalties—welfare no longer explicitly requires a father to be absent. But depending on earnings, and the number of children, marriage can still cut combined household income and benefits by a third, a staggering incentive for working class families.1

That’s because, in order to determine eligibility, modern programs count the income of both adults living in a household if those adults are married, or if they are the joint biological parents of children in that household. And when two working-class adults’ incomes are counted towards welfare-eligibility, a family is unlikely to receive benefits, relative to a family where only one adult is counted.

On paper, this means that a single mother is disqualified from substantial benefits if she lives with her child’s biological father. Yet under the common “family unit test” for welfare eligibility, a live-in boyfriend who is not the father of her children—a situation that places children in the home at a significantly higher risk of abuse2 —will not have his income counted toward determining welfare-eligibility.

But that assumes everyone follows the rules. It is often the case that unmarried biological parents can easily misrepresent their cohabitation status to authorities, thus only having one income counted toward benefit-eligibility. Ample evidence shows that such misreporting is widespread. For example, a sizeable portion of WIC (food stamps) recipients fail to report another adult in the house because that would bump them out of program eligibility.

But where it may be hard for bureaucrats to verify whether a recipient’s information is accurate with respect to cohabitation, it is easy for authorities to determine whether or not a recipient is married—because states and counties keep official databases of marriages.

The bottom line is that welfare, on paper, penalizes both biological parents living with their children, married or not. But in practice, welfare uniquely penalizes marriage and incentivizes cohabitation. Yet cohabitating relationships are uniquely unstable, and thus not ideal for children.

About half of non-marital births are to cohabitating parents, and an even greater share are to parents who view themselves as being in a long-term relationship. These cohabiting couples are most vulnerable to feel, or substantially perceive, marriage penalties at the point of having a child. While they may continue to cohabit after their child is born, they often eventually separate.

Ultimately, about two-in-three cohabiting couples with children will break up by the time their child turns 12 years old, compared to only one-quarter of children with married parents. By encouraging cohabitation, government policy is tilting the scales toward unstable families.

The Solution—Copy the Tax Code

The solution lies in taking a cue from the tax code. To account for the fact that two parents can both be earners in a family unit, the tax code increases the threshold at which most earners are taxed at a higher rate, if they are married, by at least 50 percent.3

The alternative to this system is obviously unfair to married couples. If married couples were subject to the same dollar amount where the marginal rate kicks in for single filers, their earnings—assuming both work—would face higher taxes than if they were treated as separate entities. By allowing married couples to file jointly, the tax code attempts to be neutral when it comes to marriage.4

State and federal policymakers should do the same for means-tested programs.5 Using the tax code as a general guide, safety-net eligibility thresholds should be raised for poor and working-class married couples. Programs with large marriage penalties should be specifically targeted, including Medicaid, SNAP (food stamps), and childcare subsidies.

The childcare benefit may warrant particular attention. Originally passed by Congress and signed into law by George H.W. Bush in 1990, the benefit—like other means-tested programs—is partly funded by the federal government6 but run by the states.7 Childcare benefit eligibility (and the required copayment, if eligible) is based on a parent or parents’ income and the family size, so the marriage penalty varies based on a family’s income, the cost of childcare where the family resides, and on the number of children in that family.8 The benefit has high marriage penalties in many states, and these penalties often reach into the lower middle class.

As a general guide to state policymakers, here’s how Minnesota’s childcare benefit—a program supplemented by the state, with large marriage penalties—could be reformed.

A Guide to State Welfare Reform: Minnesota’s Childcare Benefit

First, end the disparity—on paper and sometimes in practice—between biological and non-biological parents by using an “economic” test to determine eligibility, not a biological family test that fails to count the income of a live-in boyfriend.9

Second—taking a cue from the tax code—raise the income threshold of eligibility by 1.4 times for married couples who are residing together, both working, and have joint children eligible for the program, compared to a family with only one adult income, but with a similar number of children.10 For a married couple with one infant child, that would raise the eligibility threshold to $61,330, instead of $43,807.

However, leaving the reform there would mean that once a family passes the $61,330 income level, the family would experience a steep “benefit cliff.” Here, an extra dollar earned by the family, or allotted to the family because of marriage, beyond the eligibility cutoff, causes the family to suddenly lose a benefit that substantially covers around $10,000 in childcare costs per year, per child.

The solution is a phase-out period for poor married couples by means of continuing eligibility but rapidly increasing program copayments commensurate with gains in household income, which starts at 1.4 times and ends at 1.7 times the income-level to determine eligibility for a single adult with the same number of program-eligible children.11 This change helps eliminate stark, highly noticeable, disincentives to work and marriage. In the case of a married couple with one infant child, the benefit would phase out between $61,330 and $74,472.

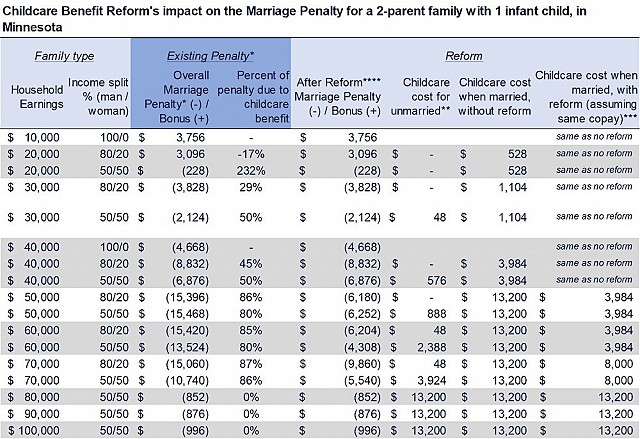

The table above,12 using data obtained from the Urban Institute’s Net Income Change Calculator,13 provides a broader picture of reform (subject to some limitations14). For example, a couple with one infant, earning $30,000 each, faces an over $13,000 marriage penalty—20% of family income, not even including means-tested healthcare programs. A substantial portion of this penalty is due to the childcare benefit because each adult on their own would qualify for that benefit. Under the reform, the two parents would remain eligible if married, cutting the marriage penalty by around $9,000, to $4,308.

Finally, reform could maintain a strict work requirement for one spouse and a minimum “hours worked” requirement for the other spouse, where the benefit only covers childcare commensurate with hours worked by that second spouse. This saves taxpayer money and allows the second spouse to work less than full-time.

Conclusion

The general changes proposed here can be applied to the childcare benefit and other safety-net programs in all American states and territories. What kind of impact could reform have? In the tax code, researchers James Alm and Leslie A. Whittington found that the “probability of marriage falls as the marriage penalty increases.” And while calculating marriage penalties in the tax code would likely involve an accountant, this is not true for means-tested welfare. Indeed, studies show that means-tested safety net recipients have a good understanding of how their behavior will affect a program’s payout. This makes sense, given the tremendous dollar value of benefits that are on the line.

It is hard enough being married; it is even harder being married while also facing the pressures and stresses of poverty. Government policy should not make these stresses and pressures worse.

As Nick Schulz puts it in his book, Home Economics, “the collapse of the intact family is one of the most significant economic facts of our time.” The path to greater social mobility in America may lie in making the safety net more marriage-neutral, eliminating the high penalization of good choices. Children would likely be the greatest beneficiaries of such a policy shift.

Willis L. Krumholz is a fellow at Defense Priorities. He holds a JD and MBA degree from the University of St. Thomas, is a CFA charter holder, and works in the financial services industry. You can follow him on Twitter @WillKrumholz.

1. Families with combined incomes between $40,000 and $80,000 usually face the largest penalties. Also, while the overall income of the family matters a great deal, marriage penalties in welfare are affected by the percent of income each potential spouse would contribute to that family. For example, women with lower earnings prospects face a reduced marriage penalty due to the “bonus” received from combining her income with the income of a higher-earning male. Yet even here, the incentive would be to cohabit, and not to marry. However, if two people with similar incomes seek to marry, which is often the case, the marriage penalty is much larger. (See also Lyman Stone, “Affordability or Achievability?” Statement before the Joint Economic Committee On Family Affordability, September 10, 2019).

2. The National Incidence Study of Child Abuse and Neglect shows that children who reside with an unrelated male in the home are about 11 times more likely to be sexually, physically, or emotionally abused. Unrelated adults in the home also significantly increase the likelihood of child-abuse deaths, meaning that when abuse does occur, it tends to be more severe and more violent. See: University of Chicago Medicine, “Unrelated adults in the home associated with child abuse deaths,” UChicagoMedicine, November 7, 2005.

3. For example, for a single tax-filer, the 24% rate kicks in at roughly $82,000 in taxable income. But for a married couple filing jointly, that rate kicks in at $165,000 and above (about a 100% increase). And while the 22% rate kicks in at roughly $50,000 in earnings for a single person, it kicks in at roughly $77,000 for a married couple filing jointly (an increase of about 54%).

4. Brad Wilcox, Chris Gersten, and Jerry Regier, “The Effect of Marriage Penalties on Economic Mobility, Poverty, and Family Formation,” 2019 (forthcoming).

5. With the exception of the Additional Child Tax Credit (ACTC) and the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC)—which run through the federal tax code—America’s welfare programs run through the states. Minnesota, like the other states and territories, receives federal money to administer federal welfare programs. Depending on the program, states have leeway to set different rules and to supplement the program as they see fit. Federal policymakers, meanwhile, can create incentives for states to act to curb marriage penalties.

6. The 1990 law was called the Child Care and Development Block Grant Act, initially passed under the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1990, and reauthorized and amended in 1996, and in 2014. Although the 2014 reauthorization made changes to ensure childcare facility quality, the 1996 changes are more consequential. The 1996 reauthorization and amendment consolidated the existing childcare programs into one block grant program, the Child Care Development Fund (CCDF). The CCDF, in turn, pulls federal money from two programs: the TANF (Temporary Assistance to Needy Families) Child Care Block Grant, and the Child Care Development Block Grant (CCDBG). States can allocate up to 30 percent of their TANF block grant for CCDF subsidies, and the remaining funds are appropriated by Congress. Specific block grants to states are appropriated based on a formula contained in the legislation.

7. Congress has attached minimum standards to the money it appropriates. Here’s Angela Rachidi , an expert on the topic: “To be eligible for child care assistance through the CCDF, families must have income below 85 percent of the state median, have a child under 13 (or under 19 with special needs), and be working or in an approved work or education activity. States are also required to prioritize children with special needs and families of very low income, and states often interpret this to mean that TANF families be given priority.” These guidelines may mean that a reforming state should seek a waiver from the Department of Health and Human Services. Yet despite these “broad federal guidelines,” states “set many of the detailed program rules and policies used to administer their programs.” For example, states have varying work requirements (see also the CCDF Policies Database).

8. Child Care Assistance Program (CCAP) Policy Manual (Issued 10/2018), Minnesota Department of Human Services.

9. An economic test asks if the adults under the same roof are sharing resources, versus looking at who is biologically related. Even better, states should implement a “working-age adults under one roof” test.

10. Under the current rules, eligibility is determined by whether or not the family’s income falls below a certain percentage of the State Median Income (SMI). Once a family is eligible for the program, incomes are allowed to temporarily move above the eligibility level before the benefit is removed, but not substantially so.

11. Logistically, this can be accomplished with a new copay schedule, and much more significant copay requirements up to the point where the copay level reaches the level of the benefit, at which point the benefit would end for that family. The reason for choosing a phase-out period that ends at 1.7 times the eligibility for a single-parent family with the same number of children is that this phase-out period ends at the exact point required to get rid of the marriage penalty—the point at which one of the parents could be single instead of married and not receive a substantial bonus for doing so, because that parent’s income is below the threshold required to qualify for the current, unreformed childcare benefit program. For example, a couple with two young children, where each adult makes $40,000 per year, would face a marriage penalty of over $15,000 per year without the phase-out, because one parent, if unmarried, would qualify for over $15,000 per year in free childcare. With the phase-out, the marriage penalty is cut significantly.

12. *Not counting marriage penalties in the Affordable Care Act subsidies or in Medicaid, which are substantial.** Assuming that the unmarried adults are not the joint biological parents of the children, or that joint biological parents are hiding their cohabitation from authorities.*** The program copay remains the same up to 1.4x the cutoff for one parent with the same number of children. Then, the copay roughly doubles on a sliding scale up to 1.7x the cutoff. **** In this instance, reform moves the eligibility for married couples from $43,807 to $61,330 using the normal copay schedule, and program eligibility remains from $61,330 to $74,472 (1.7x) at a pronounced copay, if married.

13. The Net Income Change Calculator (NICC) has several limitations that should be noted. First, because of the complexity of the inputs required to create the NICC, the calculator still uses tax and benefit rules from 2016. That doesn’t affect the results greatly, but it is a limitation. Next, these calculations do not include the Affordable Care Act (ACA, or Obamacare) subsidies and Medicaid, so the overall marriage penalty is likely even greater than what is shown.

14. Seven assumptions were made by the author when using the NICC (this is required to obtain NICC output): (1) The woman claims the children for tax purposes; (2) There has been no prior TANF or MFIP use by the family; (3) For families with two children, the ages of those children are less than one year of age and three years of age (calculated by the author but not shown in the table); (4) For families with one child, that child is assumed to be less than one year of age; (5) The childcare cost per month is $2,000 for two children, and $1,100 for one infant child (these numbers were calculated using reported Minnesota childcare costs in the metro area (see here and here; note that the correct measure of the benefit is not the state’s reimbursement rate to childcare providers, which varies by county and type of provider, but what a parent would have to pay in the absence of state support); (6) Rent is $800 per month, and; (7) No or minimal child support is received by the mother if the biological father of the children is not in the home (if there is substantial child support, that would increase the marriage or cohabitation penalty of two biological parents even further).