Highlights

- The increases in mental health issues among teens predate the pandemic by years—and in fact, some mental health indicators didn’t change at all between 2019 and 2020. Post This

- As long as teens are scrolling through Instagram more, and hanging out in person with their friends less, depression is likely to remain at historically high levels. Post This

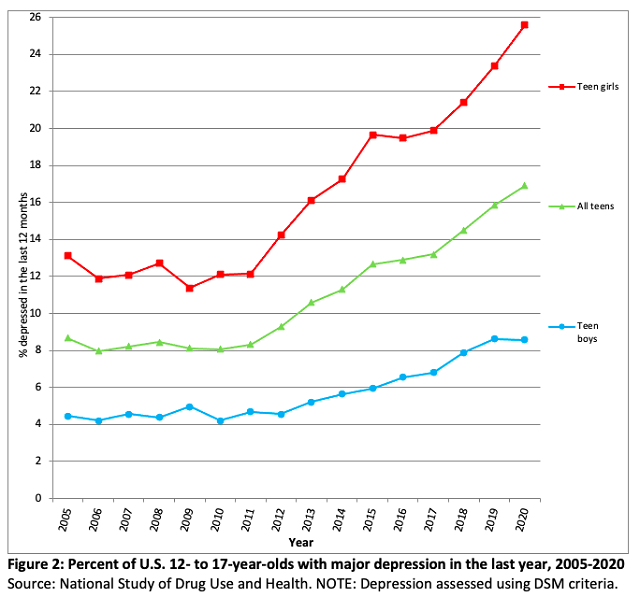

- Major depression (clinical-level depression that requires treatment) doubled between 2011 and 2019 among American teens. It then continued increasing into 2020 for girls. Post This

The COVID-19 pandemic was a rollercoaster: Every time it looked like it was over, the virus would come roaring back. The impact was especially acute for teens, who found themselves in online school, missing out on social activities, and facing the uncertainty of what might happen next.

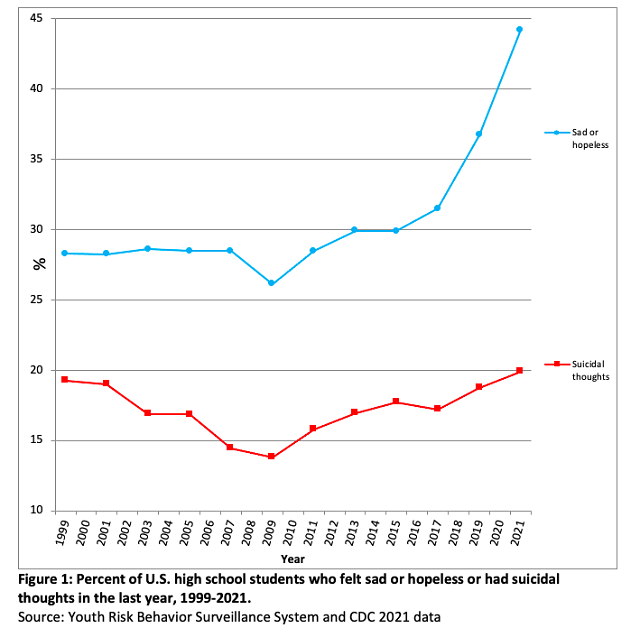

What effect did the pandemic have on teen mental health? Based on a representative survey from spring 2021, the CDC found that a stunning 44% of American teens said they felt sad or hopeless during the last year.

What might be more surprising is this: 37% of teens reported feeling sad or hopeless in spring 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic. That’s up from 26% in 2009. Suicidal thoughts also increased between 2009 and 2019 (see Figure 1). Thus, the pandemic led to more mental health issues among teens, but this was not a sudden sharp uptick or a reversal of previous positive trends—teens started to report more sadness starting 10 years ago.

This survey is not alone in showing the pattern. Major depression (clinical-level depression that requires treatment) doubled between 2011 and 2019 among American teens. It then continued increasing into 2020 for girls, though it stayed the same for boys from before to during the pandemic (see Figure 2).

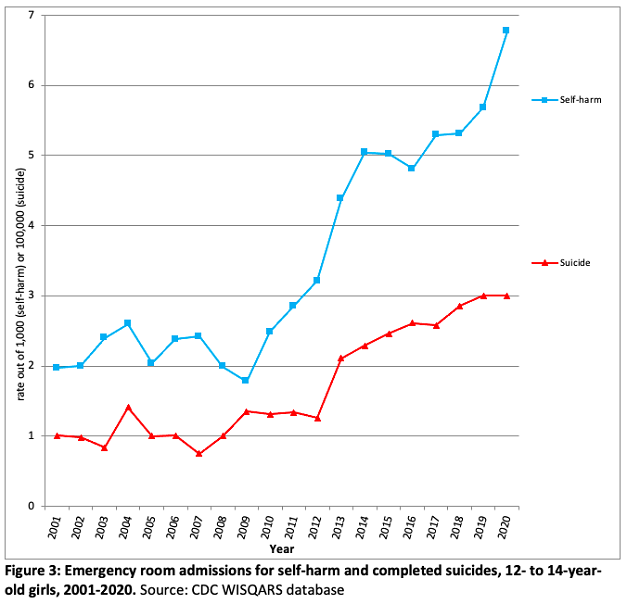

Both surveys screen a cross-section of the whole population, so the increases can’t be explained by greater help-seeking or overdiagnosis. Could teens just be more willing to admit to problems? If that were true, behaviors linked to depression such as self-harm and suicide would stay unchanged even as depression increased. But that’s not what happened: Self-harm and suicide both skyrocketed after 2010 in the U. S. (see Figure 3 among 12- to 14-year-old girls), and those results cannot be explained by self-report issues. There was a big increase in self-harm between 2019 and 2020, but thankfully not in suicide in this group.

These findings suggest two conclusions.

First, the pandemic produced complex patterns in teen mental health. It’s tempting to guess that the pandemic radically increased depression and suicide among teens, given the huge number of disruptions in their lives. Instead, the pandemic seemed to have the biggest impact on more common lower-level symptoms of depression, such as feeling sad or hopeless, while not having as big of an impact on less common and more serious issues, like suicidal thoughts or completed suicide. The exception to that pattern is the large increase in ER admissions for self-harm among young teen girls into 2020.

As more data comes in, we may also see differences between 2020 and 2021-22. The lockdowns of 2020 had some surprising silver linings for teens, like more sleep and more time with family. But by 2021, with school back in session but social lives still not back to normal and uncertainty abounding, mental health may have suffered more.

Second, these trends show that something began to go wrong in the lives of teens about 10 years ago. Although the pandemic led to much-needed attention to the issue of teen mental health, the increases in mental health issues among teens predate the pandemic by years—and in fact, some mental health indicators didn’t change at all between 2019 and 2020. That means we need to look elsewhere for the original cause.

I noticed the early increases in teen depression when I was writing my book about the generation born after 1995, titled iGen. At first, I had no idea why teen depression was increasing so much in such a short period of time. But then I noticed some big trends in teens’ social lives: They were spending less time with their friends in-person, and more time online. That tends not to be a good formula for mental health, especially for girls, and especially when that online time is spent on social media.

Thus, the high levels of teen depression are not going to go away even as the pandemic fades. Rates might decline a bit as things get back to normal, but as long as teens are scrolling through Instagram more, and hanging out in person with their friends less, depression is likely to remain at historically high levels.

If social media is responsible for even some of these increases in teen mental health problems, we need to ask what we can do.

Parents can do a few things. First, don’t allow children 12 and under to have social media accounts (under the law, the minimum age is 13, though this is not enforced). Consider waiting until well past 13 to allow social media, perhaps 16. When teens do get social media, limit the time they can spend on the apps (an hour a day is a good time limit).

Unfortunately, this effort can only go so far: Kids and teens want to be on social media because their friends are on social media and those who are not on social media are left out—this is a group problem, not just an individual family problem. Plus, many kids and teens sign up for social media accounts without their parents’ knowledge.

As a result, lawmakers are considering taking action to regulate kids and teens’ use of social media. Perhaps the age minimum of 13 will be enforced, or even raised to 16. Perhaps there will be safer versions of social media apps for 13- to 17-year-olds—at the moment, social media platforms are the same for 13-year-olds as they are for adults.

Whatever we do, it should be soon. Our kids can’t wait.

Jean M. Twenge is a Professor of Psychology at San Diego State University and is the author of iGen: Why Today's Super-Connected Kids Are Growing Up Less Rebellious, More Tolerant, Less Happy--and Completely Unprepared for Adulthood.

Editor’s Note: The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or views of the Institute for Family Studies.