Highlights

- Three of the strongest neighborhood predictors of “smaller gaps” between black and white boys in economic mobility were, to quote Chetty et al., “measures of father presence and marriage rates.” Post This

- The new Chetty et al. study actually offers further evidence that family structure appears to play an “important role” in the racial gap in economic mobility in America. Post This

"Family structure doesn’t really matter—at least when it comes to explaining the stark racial gap in upward mobility between black and white boys.” This was one popular takeaway from the latest blockbuster study on economic opportunity released this week from Stanford economist Raj Chetty and his colleagues Nathaniel Hendren, Maggie Jones, and Sonya Porter. In the study, Chetty et al. found that black boys are much less likely to realize the American Dream—economically speaking—as they move into adulthood, compared to white boys; by contrast, black girls are much more likely to do well economically as young adults, compared to white girls.

In covering this study, a number of media outlets, scholars, and commentators argued the new research showed that family structure did not have much to do with the racial gap in mobility between black and white boys. Consider Bloomberg columnist Noah Smith’s take on the study:

There’s only one problem with this interpretation: It’s not borne out by a careful review of the study.

Here are three ways the new Chetty et al. study actually indicates that family structure matters for the economic prospects of black boys, and for the racial gap in economic mobility between white and black boys.

1. Black boys prosper in neighborhoods with more black fathers.

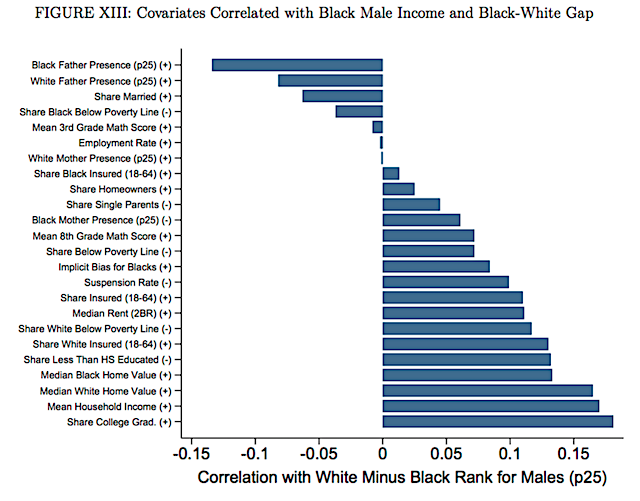

The new study suggests that neighborhood effects are powerful when it comes to predicting the gap in economic mobility between black and white boys in terms of their individual income as adults. Specifically, there is a “strong positive association between black father presence [in the neighborhood] and black males’ income.” What’s more: black boys’ employment rates are higher and their school suspension rates are lower in “areas with higher black father presence.” They also found that community marriage rates are some of the strongest predictors of smaller black-white gaps in economic mobility for boys.

Source: Chetty, Hendren, Jones, and Porter, "Race and Economic Opportunity in the United States: An Intergenerational Perspective," March 2018.

In fact, as the figure above shows, three of the strongest neighborhood predictors of “smaller gaps” between black and white boys in economic mobility are, to quote Chetty et al., “measures of father presence and marriage rates.” More specifically, the figure above indicates the racial gap was smaller when more black fathers, white fathers, and married adults lived in a black boy’s neighborhood. So much for the idea that family structure doesn’t matter much for the racial gap in boys’ individual economic mobility.

2. You cannot control for household income and say family structure doesn’t matter.

So, what led scholars and journalists like Noah Smith to conclude that this new research indicates that family structure per se does not have much to do with the racial mobility gap for black boys’ individual income as adults? Well, probably the study itself. After controlling for boys’ household income growing up, Chetty et al. themselves conclude that “parental marital status has little impact on intergenerational gaps.” For instance, they found a large racial gap in mobility persists even between black and white boys who grew up in two-parent homes at the same income level.

The problem with this strategy, however, is that there are large gaps in black and white boys’ average household income growing up, and these gaps partly follow from racial differences in family structure. As Chetty et al. note in the study, they found “two incomes for most white children but only one for most black children.” So, by controlling for household income growing up, their reported findings minimized the effect of family structure.

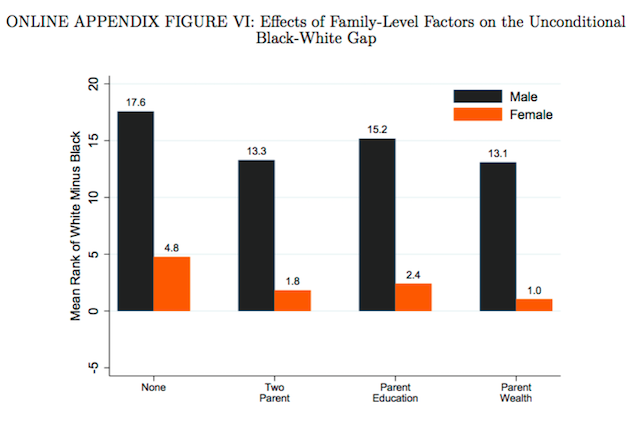

Source: Chetty, Hendren, Jones, and Porter, "Race and Economic Opportunity in the United States: An Intergenerational Perspective," March 2018.

To get the full story on family structure and the racial gap in boys’ economic mobility as they move into adulthood, I had to turn to their appendix. Online Appendix Figure VI (shown above) from their study indicates the black-white gap for boys in their adult individual income ranking shrinks by almost 25% when one factors in their family structure growing up but does not control for their household income growing up. (This figure also clearly shows that the gap for black and white girls in their adult income ranking is also related to family structure.) To put this another way, one reason the racial gap in economic mobility for boys is so large is that so many black boys live in single-parent homes with one income and so many white boys live in two-parent homes with two incomes. If you control for household income growing up, you miss the ways in which racial differences in family structure affect outcomes for boys via their impact on family income.

3. Marriage matters big time for black boys’ household income as adults.

The Chetty et al. study focuses on black and white boys’ individual income as adults. So, what is largely left out of their mobility story? Gaps in black and white boys’ household income as adults. This is striking, in part, because they use the household income of these boys to determine their income ranking growing up but then do not explore this very same variable when they have reached adulthood.

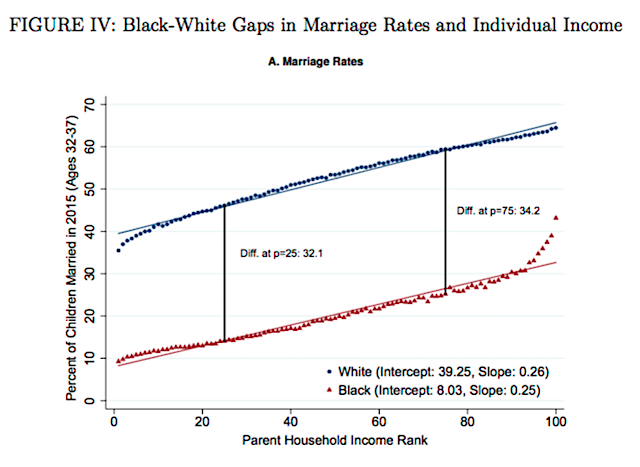

Source: Chetty, Hendren, Jones, and Porter, "Race and Economic Opportunity in the United States: An Intergenerational Perspective," March 2018.

This is a major oversight because Chetty et al. do find huge differences in the odds that black and white children will marry as adults. In fact, as the figure above indicates, there is about a 30-percentage-point gap in the odds that black and white adults marry by their 30s. Indeed, they report “[white] children at the bottom of the income distribution are as likely to be married as black children at the 97th percentile of the parental income distribution.” Part of this racial marriage gap is undoubtedly related to the differences in family structure blacks and whites also experienced growing up.

This racial difference in the odds that blacks and whites marry as thirty-somethings has large implications for the racial divide in household income as adults—including the racial divide in household income between black and white boys as adults. Even Chetty et al. acknowledge that “differences in marriage rates do play an important role in driving the gaps in household income documented above.” But they do not specifically report any of those effects—including for the racial gap in household income between black and white boys as adults.

So, this study does not allow us to know precisely how racial differences in marriage influence the gap in household income between black and white boys as they move into adulthood. But it’s safe to say, given the racial divide in marriage, that family structure has a lot to do with the racial gap in household economic mobility between black and white men.

In sum, when it comes to assessing the impact of family structure on the racial gap in economic mobility between black and white boys, this new study suggests that (1) family structure at the neighborhood level influences economic mobility for black boys, (2) family structure at the household level influences economic mobility for black boys (if you don’t control for their family income growing up), and (3) family structure in adulthood influences black boys’ household income as adults. So, sorry Noah Smith, the new Chetty et al. study actually offers further evidence that family structure seems to play an “important role” in the racial gap in economic mobility in America—including the gap between white and black boys as they move into adulthood.

W. Bradford Wilcox is a senior fellow of the Institute for Family Studies and the director of the National Marriage Project at the University of Virginia.