Highlights

With fertility rates falling in America, particularly among young people, many pundits have looked to various culprits: failure to launch, student loans, the Great Recession, excessive housing costs, or any number of other explanations. One of the more entertaining theories is that Millennials have very different values than older generations, particularly concerning pet ownership. The chorus of pundits is nearly uniform: Millennials are crazy to choose pets over babies, Millennials are smart to choose pets over babies, Millennials are weird to choose animals over people, 20-something women are choosing pets over kids, Millennials are opting for pets not parenthood, etc. Everyone agrees: Millennials are pet crazy.

But all of these studies face a major problem: there’s very little actual data about pet ownership, and the data that does exist is paywalled data produced by pet-industry surveys. The studies cited are one-off, comparatively small-sample marketing studies, not rigorous evaluations of population characteristics. They’re full of curious advice for marketers, like this study, which suggests that the Millennial pet owner is fundamentally irrational. On the other hand, no major population survey like the American Community Survey, General Social Survey, or Current Population Survey asks about pet ownership. The last public Gallup poll I could find on the question was in 2007.

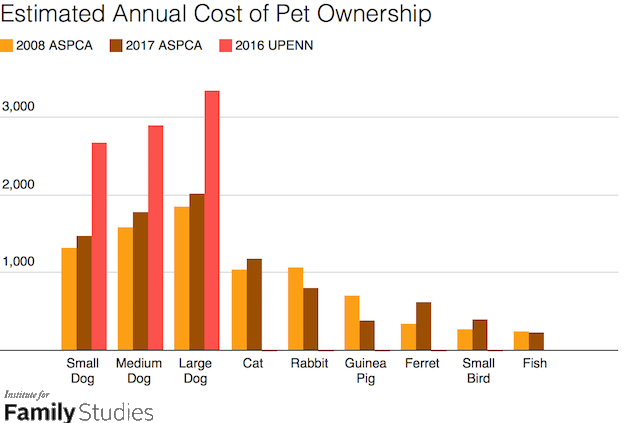

However, some very limited data does exist. One thing that comes up a lot is the rising expenditures made on a per-pet basis, which is fairly easy to track. The American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA) estimates the cost of pet ownership each year. Comparing 2008 to 2017 shows a substantial increase for most pet categories.

But that third estimate, from an independent study by veterinarians at the University of Pennsylvania, suggests an even higher per-pet cost, though that study had no time series data available.

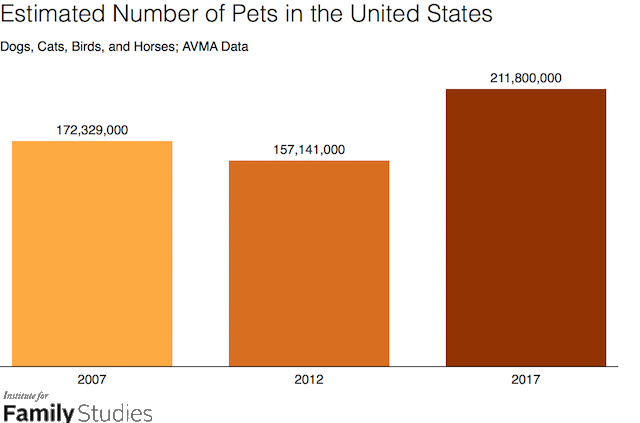

We can also simply look at how many pets there are in America. The American Pet Products Association (APPA) and the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) both survey pet ownership regularly. Unfortunately, both restrict access to their data, so only a few limited conclusions can be made. But from the small amount of data we can see, the number of pets in America (defined here as dogs, cats, birds, and horses) fell from 2007 to 2012 but has since risen substantially.

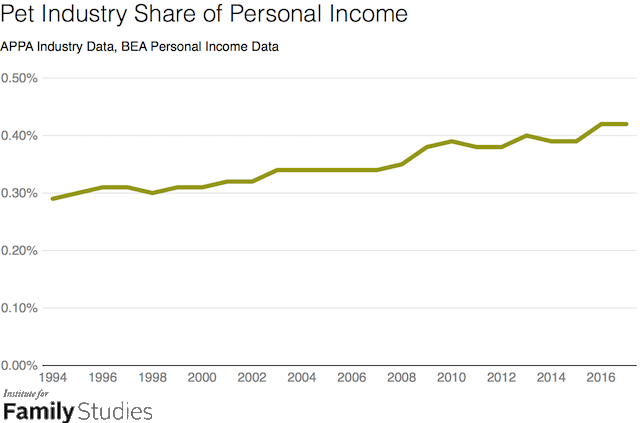

We can also look at the revenues reported by APPA members each year from their sales in the pet industry. We can then divide these sales by personal income to get an estimate of how much of their money Americans are spending on pets, controlled for inflation or income changes. The market research I cited above shows that there is reason to think that spending is rising, and at least some of this is due to greater spending-per-pet on non-essential items: pet clothing, specialty food, more toys, more pet classes, etc. Or, rather, these items seem non-essential to many older pet owners, but may actually be “essential” for dogs yanked out of a natural environment where they can run and play, and cooped up in a small apartment. A more urbanized America must spend more per pet to make that pet’s life tolerable.

Tellingly, there was no “recession” in pet spending, as the figure above indicates. Even as Americans’ incomes suffered, pet spending rose, causing its share of income to jump markedly. This, despite the total number of pets probably declining, which suggests that spending-per-pet did indeed jump.

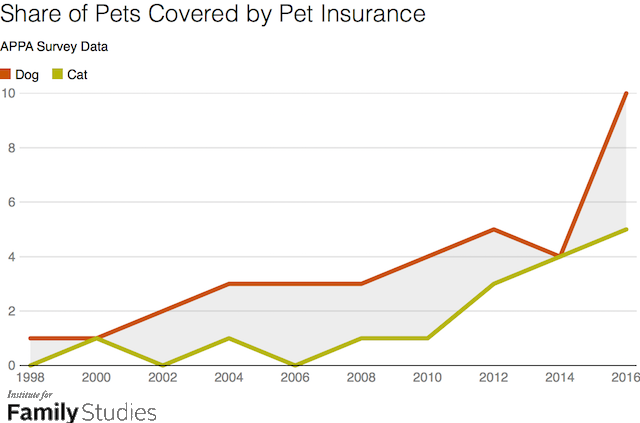

We can also see the growth of previously-non-essential categories of pet spending in the limited time-series data provided by APPA. They provide data of the share of dogs and cats covered by pet insurance, as shown below.

The share of dogs and cats covered by insurance is rising. This suggests both that pet owners increasingly see their pets as valuable and hard to replace, suggesting they make substantial monetary investments in them, but also is itself a rising cost factor: insurance money is “new spending.” APPA also reports that the share of pet owners who spend money on parties for their pets, electronic tracking of pets, or pet-calming devices is rising too.

But, hold on, the APPA’s been surveying this issue for a long time, since 1988, and they find that pet ownership in 1988 was about 56%, compared to 68% today: that is not a particularly rapid increase for a 30-year period. Is this really a seismic shock in pet ownership, or is the main factor changing social norms about how much people should spend on pets? Given extant data, it’s hard to say. But whether it’s higher per-pet spending, or more pets, the conclusion that pets are consuming a larger share of American earnings seems clear.

But does this have any impact on fertility?

One way we can test this is to find groups that have very different pet ownership rates, for example, single people versus married people. Perhaps fulfilling a stereotype, APPA reports that dog owners are more likely to be married, while cat owners less so, although a more detailed study of California suggests that both dog and cat owners have higher marriage rates than the general population. Meanwhile, whites are far more likely to own pets than other races.

So we can ask ourselves: how did fertility change for people ages 22-35 once we control for race or marital status? Did more pet-prone groups have bigger fertility declines?

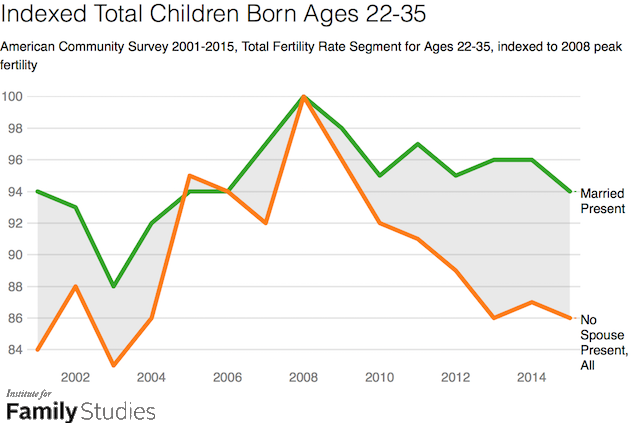

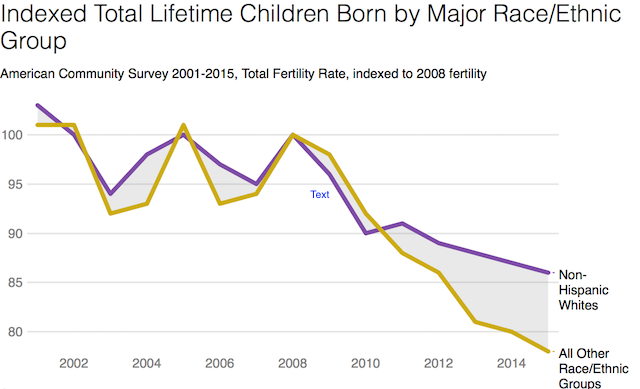

It turns out, the answer is “no.” Fertility fell much more for unmarried young people than for married young people, and it fell more for less-pet-intensive minorities than for non-Hispanic whites.

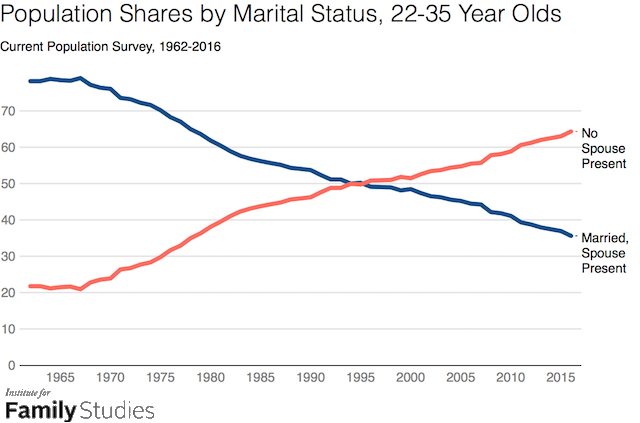

While we can’t observe pet-owner-specific fertility, at least the aggregate correlates give comparatively little support to the idea that pets are replacing kids on a meaningful scale. However, it does seem there may be some effect: while singles have lower total pet ownership, pet ownership is reportedly rising particularly fast among single women, even as fertility has fallen for this group. So that may be a real effect. The problem is, single women already had far lower fertility than married women, so declining single fertility should not create a huge drag on total fertility—unless, of course, the share of women who are single is simultaneously rising rapidly. And that turns out to be exactly what is happening.

With delayed marriage, the share of young people who are married has fallen, and they spend less of their 20s and early 30s in marriage than previous generations did. As a result, they have lower total fertility in this period, because married fertility is reliably 2-5 times as high as unmarried fertility. As singles make up a larger share of the population, this composition change ends up driving a huge share of the aggregate change in fertility.

Meanwhile, singles may also see their pets differently than families do: singles often see pets as “family members,” while family-owners are more likely to see pets as property. But while “pet-parents” may rhetorically describe their pets as “children,” the correspondent decline in both single-person fertility and marriage among young people suggests that pets may be replacing two different family members. For some owners, pets replace kids. But for many, the companionship provided by a pet replaces spouses. Pets are often described as providing companionship, emotional support, security, or a sense of “home” or rootedness for “pet-parents”: but these aren’t traits that describe a child. These are traits that describe a husband or a wife. With my generation postponing the commitment of marriage due to any number of other reasons, the need for a reliable companion who is committed to stay until death do it part may simply be transferred onto pets rather than people.

In other words, there probably are two separate connections between fertility and pet ownership: rising pet ownership may be replacing single-motherhood to some extent, but more prominently, young people are pushed by many factors to delay marriage, and so spend more years in singleness, without reliable companionship. As a result, they invest—often expensively so—in a truly reliable companion: a pet.

Lyman Stone is a Research Fellow at the Institute for Family Studies, and an International Economist at the U.S. Department of Agriculture, where he forecasts cotton market conditions. He blogs about migration, population dynamics, and regional economics at In a State of Migration.