Highlights

- On average, early-marrieds enjoy slightly higher marital quality than later-marrieds as measured by such outcomes as relationship satisfaction, sexual satisfaction, teamwork, and communication. Post This

- At least today, those marrying in their early twenties appear a little more likely to enjoy wedded bliss than those marrying later. Post This

- Marriage doesn’t have to be a crowning capstone that signals a status of successful young adult achievement, a status that too many will find difficult to attain. For many, marriage can be the solid cornerstone on which to frame a meaningful family life. Post This

Most American adults aspire to be married. But for many today, marriage is supposed to be a capstone achievement rather than a cornerstone of young adult life. The “capstone model”1 says you are supposed to have all your ducks in a row—education, some professional success, and a clear adult identity—before you marry. The median age at first marriage has increased over the past 50 years in the United States, from age 23 in 1970 to about 30 in 2021 for men, and from 21 in 1970 to 28 in 2021 for women, with no sign that this upward trend is leveling off. Indeed, a recent national survey of Millennials (ages 18-33) found the vast majority agree that marrying later means that both people will be more mature, more likely to have achieved important personal goals, and more likely to have personal finances in order.2 Moreover, they believe that later marriages will be more stable and higher quality. That is the widely accepted cultural narrative.

But do later marriages consistently provide better prospects for marital success than earlier marriages? We often hear about the advantages of capstone marriage, but there has been little empirical investigation into those supposed advantages. In a new State of Our Unions: 2022 report published by the National Marriage Project, The Wheatley Institution, and the School of Family Life at Brigham Young University, my team of researchers3 reports an empirical investigation of potential differences and similarities between early-marrieds (ages 20-24), who are more aligned with a “cornerstone marriage” model, and later-marrieds (25+), who are more aligned with a capstone marriage model, on a wide range of marital outcomes. (It is important to note that our operational definition of cornerstone marriage is for those who married in their early 20s, not in their teens, who still are at a higher risk.) To do so, we use three recent datasets4 with large, nationally representative U.S. samples and a rich set of marital outcomes.

Overall, our analyses find few reasons to favor capstone marriages over cornerstone marriages. For most comparisons, we found no statistically significant differences between early-marrieds and later-marrieds. When differences surfaced, they were almost always small in magnitude—and they tended to favor early-marrieds.

To be sure, we find weak (mostly non-significant) evidence that capstone marriages are more stable than cornerstone marriages. In other words, waiting to marry was linked to slightly more marital stability in some analyses. However, there is new research that complicates that story. Lyman Stone and Brad Wilcox found that marriages formed around age 30 are the most stable for those who cohabit first, whereas twentysomething marriages formed between ages 22 and 30 are the most stable for those who do not live together prior to marrying.

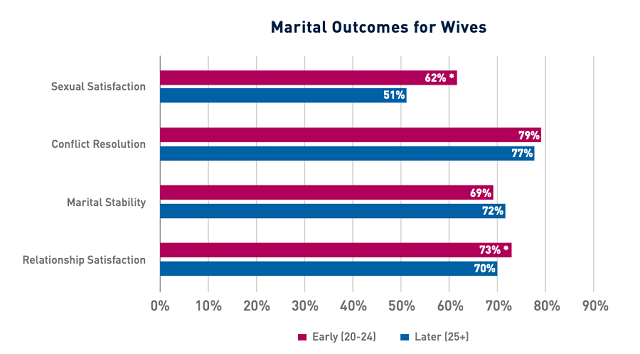

Source: State of Our Unions 2022, National Marriage Project at UVA, The Wheatley Institution, BYU School of Family Life

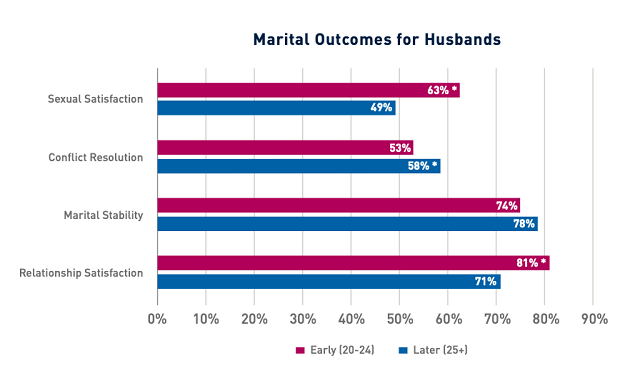

But when it comes to marital quality, the story is clearer and more positive for cornerstone marriages, especially for men. We find evidence that, on average, early-marrieds enjoy slightly higher marital quality than later-marrieds as measured by such outcomes as relationship satisfaction, sexual satisfaction, teamwork, and communication.5 This is especially the case for husbands.

Source: State of Our Unions 2022, National Marriage Project at UVA, The Wheatley Institution, BYU School of Family Life

These findings run counter to the cultural narrative that those who marry early will struggle in their relationships. At least today, those marrying in their early twenties appear a little more likely to enjoy wedded bliss than those marrying later. Moreover, religious differences don’t explain away these findings; it is not faith per se but something else that seems to account for these differences.

It's important to acknowledge that what scholars call “selectivity” may factor into these findings. What that means is that, especially today, certain types of couples are more likely to select into younger marriages and their distinctive values, relationship experiences, and traits likely figure in these patterns. We looked for differences between early-marrieds and later-marrieds among many of the usual-suspect demographic factors, but we didn’t find a lot of differences. Not surprisingly, later-marrieds had completed more education. Racial/ethnic differences were not large; Hispanics may be a little more likely to marry early. We expected to find that early-marrieds were more religious, but across different datasets and different measures, religious differences were generally small and not consistent. One dataset looked at the importance of life roles but even here differences were minimal. Both early-marrieds and later-marrieds highly valued marriage, work, and leisure; no differences there. The early-married group put a little more value on the parenting role.

We suspect that those who marry in their early 20s do so because they want to, not because they have to marry or because a strong cultural script pulls them in that direction. They may be unusually dedicated to marriage—or one another—although our analyses found that early-marrieds were only slightly more committed to their relationship than later-marrieds. And later-marrying couples may have some significant challenges to surmount of their own, such as the difficulty of merging a set identity into the crucial “we” -dentity of married life after a lengthy young adulthood focused on self. Also, it’s important to mention that a capstone model of marriage can seem unobtainable to less advantaged couples these days.

Cornerstone couples swim against a social current that too often questions the wisdom of their choices. Our findings call into question that cultural blueprint. Marriage doesn’t have to be a crowning capstone that signals a status of successful young adult achievement, a status that too many will find difficult to attain. For many, marriage can be the solid cornerstone on which to frame together the walls and windows and rooms of a meaningful life for the couple and their children. For that reason, society could be more tolerant—and even supportive—of 21st century cornerstone marriages than it now is.

Read more about the 2022 State of Our Unions report here or download a copy.

Alan Hawkins is a professor of family life at Brigham Young University. Brad Wilcox is nonresident senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI) and director of the National Marriage Project at the University of Virginia. Jason Carroll is associate director of the Wheatley Institution and a professor of family life at Brigham Young University.

1. Andrew Cherlin generally is credited with the term, “capstone marriage,” in his analysis of the deinstitutionalization of marriage. See: Cherlin, A. J. (2004). The deinstitutionalization of American marriage. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66(4), 848-861.

2. See: Willoughby, B. J., & James, S. L. (2017). The marriage paradox: Why emerging adults love marriage yet push it aside. Oxford University Press.

3. Alan J. Hawkins, Jason S. Carroll, Anne Marie Wright Jones, and Spencer L. James.

4. Our primary dataset was the Couple Relationships and Transition Experiences (CREATE) study that has followed a national probability sample of 2,181 newly married U.S. couples since 2015. (We report data from year 4 of the study and exclude a few couples who married after the age of 50.) We also used the Study of Successful Marital and Adult Role Transitions (SMART) study that surveyed in 2016 a nationally representative sample of adults ages 30–35 reporting retrospectively on their young adult experiences in their 20s, with 1,845 of the respondents being married. A third Divorce Decision-making Study (DDMak) that surveyed in 2015 a nationally representative sample of 3,000 married individuals (not couples) ages 25–50.

5. These findings were robust with controls for religiosity, education, and length of marriage in our primary dataset. In a second dataset, controls reduced the differences between early-marrieds and later-marrieds on a couple of outcomes. Also, a more refined breakdown of age at marriage – distinguishing those who married between 25-29 from those who marriage at 30+ still produced a similar pattern of findings as the simpler breakdown (comparing those who married ate ages 20-24 with those who married 25+).