Highlights

- New research shows that the overwhelming majority of parents find raising kids rewarding and enjoyable. Post This

- It may cause a fair amount of exhaustion and worry, but overall most people aren’t getting clobbered by having kids. Post This

- Turns out parenting isn't quite the slog we thought it was. Post This

The Pew Research Center recently published a new survey on parenting that has been getting a lot of attention. The survey breaks down an array of attitudes about parenting by race, gender, and income levels. It’s fascinating stuff. But for all the deep granular data, there was one thing that surprised me more than anything else but which is largely getting glossed over in the ensuing conversation: The vast majority of parents actually enjoy parenting, find it rewarding, and see it as a key part of their identities.

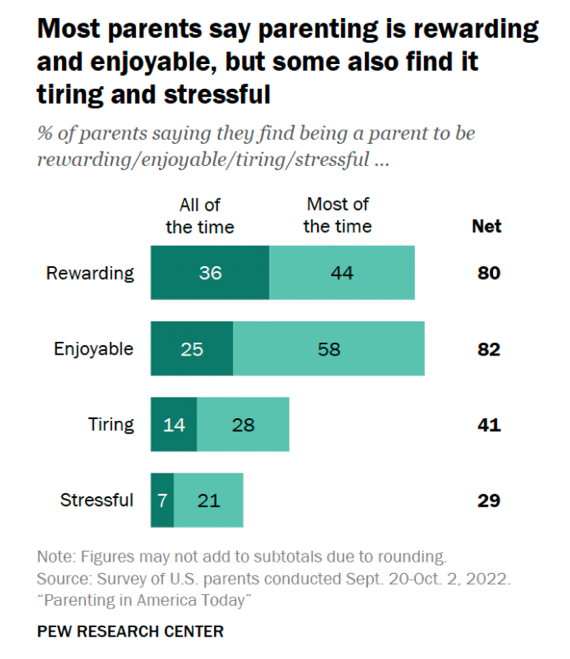

Specifically, 36% of Pew’s respondents said that being a parent is enjoyable all the time. Another 44% said it’s enjoyable most of the time. That’s a total of 80% of respondents who described parenting as enjoyable. Similarly, 25% described parenting as rewarding all the time, and 58% described it as rewarding most of the time, for a total of 82%.

Those are overwhelming majorities.

More surprising still, lower-income parents are actually more likely to see parenting as enjoyable and rewarding all the time than parents with higher and middle incomes.

On top of that, 30% of respondents said that being a parent is “the most important aspect to who they are as a person.” Another 57% said it was “one of the most important aspects to who they are as person.” Together, those add up to 87% of respondents who see being a parent as a key part of their identity.

These findings shocked me.

Recent research notwithstanding, when I comb social media, read articles on parenting, or even just talk to fellow parents, overwhelmingly the impression I get is that parenting is a slog. The latest viral example in the genre was published earlier this week in The Cut; it described moms whose families make multiple six figures, but who still feel burned out and routed by their more successful neighbors. They sounded miserable.

Closer to home, I was recently talking to someone (without kids) who said my wife and I are the only parents she knows who don’t make the experience sound crushingly difficult. And when I was writing this post, I opened up TikTok to see if any parenting content would pop up. Within seconds, I was watching videos with people saying that the most difficult part of parenting is “the kids.” It was a joke, but still captures the way parenting is typically framed as a trial to be endured

Even the framing around the Pew research reinforces this idea. Pew’s own subhead focused on parental worry and how parenting is harder than people expected. The New York Times went with the headline “How Parenting Today Is Different, and Harder.”

Headlines are supposed to offer a surprising kernel of information that entices someone to read on. But given the prevailing mood about parenting, I don't think the most surprising thing about the Pew survey was its findings on exhaustion, stress, and worry (which I'll get into more below). Instead, the most surprising thing about this Pew research is that nearly everyone who is a parent likes being a parent. Turns out parenting isn't quite the slog we thought it was.

I’ll say that again for emphasis: The vast majority of parents find their experience enjoyable and rewarding. It’s not everyone, of course, but it is most parents.

So what’s going on? Why is there this gap between how parents feel and how parenting gets framed in public discourse?

One possible answer is shifting priorities.

In an insightful New York Times column, Ross Douthat notes that the survey reveals “upper-class angst” about parenting, and wonders if a “quasi-religious commitment to fulfillment through intense professional commitment”—or “workism”—is getting in the way:

But the Pew data suggests a way that economic and cultural forces can unite to shape the way that people set priorities for adulthood. It’s possible, in this reading of the evidence, to grow up with the same theoretical aspirations for marriage and family as past generations, but also receive a strong cultural message that everything a different society might regard as fundamentally bigger than your job—religious faith and political ideology as well as love, marriage, kids, grandkids—is actually secondary, and however many children you want on paper, the essence of a valuable adulthood rests in work and money.

People have always had to work, but the idea here is that jobs have shifted from a means to an end—for example, a way to support one’s family—to an end in themselves. And in that context, family starts to seem like an obstruction. The Pew research suggests this effect is most pronounced among successful professional class strivers—or the kind of people highlighted in the piece from The Cut.

Another thing that’s probably going on here is that parenting often is exhausting, and exhaustion sounds like the antithesis of happiness. It wipes you out, the logic goes, and so it’s a problem in need of solutions. A former colleague of mine made this argument in her coverage of the Pew research, arguing that “while caring for children can be exhausting and stressful, that does not have to be its base temperature. […] There’s nothing inevitable about it.”

Maybe. But was there ever a time when parenting wasn’t stressful and exhausting? Just to point out one example, Harvard evolutionary biologist David Haig has hypothesized that babies cry at night and wake up their parents in order to disrupt their mother’s sleep, extend the lactation period, and delay the arrival of another sibling. Sleepless nights aren’t a bug, they’re a feature. We literally evolved to stress out our parents, and we’ve been doing it for hundreds of thousands of years.

Despite the many shortcomings of modern parenting life, despite shifting values, despite professional class angst, despite workism and exhaustion, it turns out that being a parent is still a worthwhile experience for most people.

I bring this up to point out that stress and exhaustion probably are inevitable parts of parenting, but that fact doesn’t mean parenting can’t also be rewarding. These aren’t mutually exclusive experiences.

Pew’s research also shows that stress and exhaustion may be less widespread than they seem: Only 41% of respondents told Pew that parenting was tiring either all or most of the time, and 29% said it was stressful all or most of the time. These numbers surprised me; it means only a minority of parents are stressed out and tired most of the time. I thought it was everyone?

Either way though, the stress, exhaustion and worry that go along with parenting today hasn’t been enough to keep the experience from being rewarding for most people. That’s a pretty big deal.

Another related finding in the survey was that 62% of respondents felt that parenting was either “a lot harder” or “somewhat harder” than they expected.

My theory on this finding it has to do with the way different generations talk about the challenges of parenting. My mom, for instance, was a very frugal mother of eight kids living in a house that’s smaller than my current residence. I suspect being a parent for her involved a lot of stress and worry. But she was also relentlessly pro-motherhood and pro-family. I suspect that for many baby boomers such as my mom, the exhausting parts of parenthood were accepted as a given, similar to how you accept that you’ll be exhausted if you run a marathon. No one warns you that marathon running will be tiring because that should be obvious.

Millennial and Gen Z parents may be used to a different kind of dialog. And they (we) may not feel prepared by, or have inherited the assumptions of, their parents. On top of that, if you prioritize work, professional success, or more abstract values like self actualization, it may come as a surprise that the experience previous generations insisted was great is also hard.

But whatever the cause of this gap between expectation and reality, it’s worth keeping in mind that it hasn’t derailed parents’ enjoyment. People found that having kids was harder than they thought, but they still dig it.

Obviously difficulty exists on a spectrum, and there comes a point when something becomes so exhausting or so stressful that it’s no longer rewarding. My heart goes out to the people who are experiencing that when it comes to parenting. There’s plenty we could and should do to make parenting better, and I’m not arguing that the experience is perfect as is right now. The whole reason I started writing about families in the first place was because I became convinced that raising kids today is harder than it needs to be, or than it has been historically.

But despite the many shortcomings of modern parenting life, despite shifting values, despite professional class angst, despite workism and exhaustion, it turns out that being a parent is still a worthwhile experience for most people. It may cause a fair amount of exhaustion and worry, but overall, most people aren’t getting clobbered by having kids. In the end, that’s pretty remarkable.

I was thinking about this a few nights ago while watching the show Andor with my wife. There’s a moment when Andor, the title character, prepares to go on the run. He asks his mother to join him, but she declines.

He pleads, “I’ll be worried about you all the time.”

“That’s just love,” she replies.

I know it’s just a TV show, but I think that’s about right: To worry, to stress out, to be exhausted, that’s what it is to love someone.

Jim Dalrymple II is a journalist and author of the Nuclear Meltdown newsletter about families. He also covers housing for Inman and has previously worked at BuzzFeed News and the Salt Lake Tribune.

Editor’s Note: This essay appeared first in the author’s newsletter, Nuclear Meltdown, and has been used here with his permission. It has been lightly edited.